Chapter 1 – Introduction to Communication Studies

How did humans develop the ability to communicate? Are humans the only creatures on earth that communicate? What purpose does communication serve in our lives? Answers to these historical, anthropological, and social-scientific questions provide part of the diversity of knowledge that makes up the field of communication studies. As a student of communication, you will learn that there is much more to the field than public speaking, even though the origins of communication studies are traced back thousands of years to ancient Greek philosophers and teachers like Plato and Aristotle who were the first to systematically study and write about speech. Communication students and scholars also study basic communication processes like nonverbal communication, perception, and listening, as well as communication in various contexts, including interpersonal, group, intercultural, and media communication.

Communication has been called the most practical of the academic disciplines. Even the most theoretical and philosophical communication scholars are also practitioners of communication, and even though you have likely never taken another communication studies class, you have a lifetime of experience communicating. This experiential knowledge provides a useful foundation and a starting point from which you can build the knowledge and practice the skills necessary to become a more competent and ethical communicator. I always inform my students that I consider them communication scholars while they are taking my class, and I am pleased to welcome you to the start of your communication studies journey. Whether you stay on this path for a semester or for much longer, studying communication has the potential to enrich your life in many ways.

1.1 Forms of Communication

Learning Objectives

Define communication.

List the five forms of communication.

Distinguish among the five forms of communication.

Review the various career options for students who study communication.

For our purposes in this book, we will define communication as the process of generating meaning by sending and receiving verbal and nonverbal symbols and signs that are influenced by multiple contexts. This definition builds on other definitions of communication that have been rephrased and refined over many years. In fact, since the systematic study of communication began in colleges and universities a little over one hundred years ago, there have been more than 126 published definitions of communication. Frank E. X. Dance and Carl E. Larson, The Functions of Human Communication: A Theoretical Approach (New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, 1976), 23.

Now let’s turn to a discussion of the five major forms of communication.

Forms of Communication

Forms of communication vary in terms of participants, channels used, and contexts. The five main forms of communication, all of which will be explored in much more detail in this book, are intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, public, and mass communication. This book is designed to introduce you to all these forms of communication. If you find one of these forms particularly interesting, you may be able to take additional courses that focus specifically on it. You may even be able to devise a course of study around one of these forms as a communication major. In the following we will discuss the similarities and differences among each form of communication, including its definition, level of intentionality, goals, and contexts.

Intrapersonal Communication

Intrapersonal communication is communication with oneself using internal vocalization or reflective thinking. Like other forms of communication, intrapersonal communication is triggered by some internal or external stimulus. We may, for example, communicate with our self about what we want to eat due to the internal stimulus of hunger, or we may react intrapersonally to an event we witness. Unlike other forms of communication, intrapersonal communication takes place only inside our heads. The other forms of communication must be perceived by someone else to count as communication. So what is the point of intrapersonal communication if no one else even sees it?

Intrapersonal communication serves several social functions. Internal vocalization, or talking to ourselves, can help us achieve or maintain social adjustment. Frank E. X. Dance and Carl E. Larson, Speech Communication: Concepts and Behaviors (New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, 1972), 51. For example, a person may use self-talk to calm himself down in a stressful situation, or a shy person may remind herself to smile during a social event. Intrapersonal communication also helps build and maintain our self-concept. We form an understanding of who we are based on how other people communicate with us and how we process that communication intrapersonally. The shy person in the earlier example probably internalized shyness as a part of her self-concept because other people associated her communication behaviors with shyness and may have even labeled her “shy” before she had a firm grasp on what that meant. We will discuss self-concept much more in Chapter 2 “Communication and Perception”, which focuses on perception. We also use intrapersonal communication or “self-talk” to let off steam, process emotions, think through something, or rehearse what we plan to say or do in the future. As with the other forms of communication, competent intrapersonal communication helps facilitate social interaction and can enhance our well-being. Conversely, the breakdown in the ability of a person to intrapersonally communicate is associated with mental illness. Frank E. X. Dance and Carl E. Larson, Speech Communication: Concepts and Behaviors (New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, 1972), 55.

Sometimes we intrapersonally communicate for the fun of it. I’m sure we have all had the experience of laughing aloud because we thought of something funny. We also communicate intrapersonally to pass time. I bet there is a lot of intrapersonal communication going on in waiting rooms all over the world right now. In both of these cases, intrapersonal communication is usually unplanned and doesn’t include a clearly defined goal. Frank E. X. Dance and Carl E. Larson, Speech Communication: Concepts and Behaviors (New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, 1972), 28. We can, however, engage in more intentional intrapersonal communication. In fact, deliberate self-reflection can help us become more competent communicators as we become more mindful of our own behaviors. For example, your internal voice may praise or scold you based on a thought or action.

Of the forms of communication, intrapersonal communication has received the least amount of formal study. It is rare to find courses devoted to the topic, and it is generally separated from the remaining four types of communication. The main distinction is that intrapersonal communication is not created with the intention that another person will perceive it. In all the other levels, the fact that the communicator anticipates consumption of their message is very important.

Interpersonal Communication

Interpersonal communication is communication between people whose lives mutually influence one another. Interpersonal communication builds, maintains, and ends our relationships, and we spend more time engaged in interpersonal communication than the other forms of communication. Interpersonal communication occurs in various contexts and is addressed in subfields of study within communication studies such as intercultural communication, organizational communication, health communication, and computer-mediated communication. After all, interpersonal relationships exist in all those contexts.

Interpersonal communication can be planned or unplanned, but since it is interactive, it is usually more structured and influenced by social expectations than intrapersonal communication. Interpersonal communication is also more goal oriented than intrapersonal communication and fulfills instrumental and relational needs. In terms of instrumental needs, the goal may be as minor as greeting someone to fulfill a morning ritual or as major as conveying your desire to be in a committed relationship with someone. Interpersonal communication meets relational needs by communicating the uniqueness of a specific relationship. Since this form of communication deals so directly with our personal relationships and is the most common form of communication, instances of miscommunication and communication conflict most frequently occur here. Frank E. X. Dance and Carl E. Larson, Speech Communication: Concepts and Behaviors (New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, 1972), 56. Couples, bosses and employees, and family members all have to engage in complex interpersonal communication, and it doesn’t always go well. In order to be a competent interpersonal communicator, you need conflict management skills and listening skills, among others, to maintain positive relationships.

Group Communication

Group communication is communication among three or more people interacting to achieve a shared goal. You have likely worked in groups in high school and college, and if you’re like most students, you didn’t enjoy it. Even though it can be frustrating, group work in an academic setting provides useful experience and preparation for group work in professional settings. Organizations have been moving toward more team-based work models, and whether we like it or not, groups are an integral part of people’s lives. Therefore the study of group communication is valuable in many contexts.

Group communication is more intentional and formal than interpersonal communication. Unlike interpersonal relationships, which are voluntary, individuals in a group are often assigned to their position within a group. Additionally, group communication is often task focused, meaning that members of the group work together for an explicit purpose or goal that affects each member of the group. Goal-oriented communication in interpersonal interactions usually relates to one person; for example, I may ask my friend to help me move this weekend. Goal-oriented communication at the group level usually focuses on a task assigned to the whole group; for example, a group of people may be tasked to figure out a plan for moving a business from one office to another.

You know from previous experience working in groups that having more communicators usually leads to more complicated interactions. Some of the challenges of group communication relate to task-oriented interactions, such as deciding who will complete each part of a larger project. But many challenges stem from interpersonal conflict or misunderstandings among group members. Since group members also communicate with and relate to each other interpersonally and may have preexisting relationships or develop them during the course of group interaction, elements of interpersonal communication occur within group communication too. Chapter 13 “Small Group Communication” of this book, which deals with group communication, will help you learn how to be a more effective group communicator by learning about group theories and processes as well as the various roles that contribute to and detract from the functioning of a group.

Public Communication

Public communication is a sender-focused form of communication in which one person is typically responsible for conveying information to an audience. Public speaking is something that many people fear, or at least don’t enjoy. But, just like group communication, public speaking is an important part of our academic, professional, and civic lives. When compared to interpersonal and group communication, public communication is the most consistently intentional, formal, and goal-oriented form of communication we have discussed so far.

Public communication, at least in Western societies, is also more sender focused than interpersonal or group communication. It is precisely this formality and focus on the sender that makes many new and experienced public speakers anxious at the thought of facing an audience. One way to begin to manage anxiety toward public speaking is to begin to see connections between public speaking and other forms of communication with which we are more familiar and comfortable. Despite being formal, public speaking is very similar to the conversations that we have in our daily interactions. For example, although public speakers don’t necessarily develop individual relationships with audience members, they still have the benefit of being face-to-face with them so they can receive verbal and nonverbal feedback. Later in this chapter, you will learn some strategies for managing speaking anxiety, since presentations are undoubtedly a requirement in the course for which you are reading this book. Then, in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech”, Chapter 10 “Delivering a Speech”, and Chapter 11 “Informative and Persuasive Speaking”, you will learn how to choose an appropriate topic, research and organize your speech, effectively deliver your speech, and evaluate your speeches in order to improve.

Mass Communication

Public communication becomes mass communication when it is transmitted to many people through print or electronic media. Print media such as newspapers and magazines continue to be an important channel for mass communication, although they have suffered much in the past decade due in part to the rise of electronic media. Television, websites, blogs, and social media are mass communication channels that you probably engage with regularly. Radio, podcasts, and books are other examples of mass media. The technology required to send mass communication messages distinguishes it from the other forms of communication. A certain amount of intentionality goes into transmitting a mass communication message since it usually requires one or more extra steps to convey the message. This may involve pressing “Enter” to send a Facebook message or involve an entire crew of camera people, sound engineers, and production assistants to produce a television show. Even though the messages must be intentionally transmitted through technology, the intentionality and goals of the person actually creating the message, such as the writer, television host, or talk show guest, vary greatly. The president’s State of the Union address is a mass communication message that is very formal, goal oriented, and intentional, but a president’s verbal gaffe during a news interview is not.

Mass communication differs from other forms of communication in terms of the personal connection between participants. Even though creating the illusion of a personal connection is often a goal of those who create mass communication messages, the relational aspect of interpersonal and group communication isn’t inherent within this form of communication. Unlike interpersonal, group, and public communication, there is no immediate verbal and nonverbal feedback loop in mass communication. Of course you could write a letter to the editor of a newspaper or send an e-mail to a television or radio broadcaster in response to a story, but the immediate feedback available in face-to-face interactions is not present. With new media technologies like Twitter, blogs, and Facebook, feedback is becoming more immediate. Individuals can now tweet directly “at” (@) someone and use hashtags (#) to direct feedback to mass communication sources. Many radio and television hosts and news organizations specifically invite feedback from viewers/listeners via social media and may even share the feedback on the air.

The technology to mass-produce and distribute communication messages brings with it the power for one voice or a series of voices to reach and affect many people. This power makes mass communication different from the other levels of communication. While there is potential for unethical communication at all the other levels, the potential consequences of unethical mass communication are important to consider. Communication scholars who focus on mass communication and media often take a critical approach in order to examine how media shapes our culture and who is included and excluded in various mediated messages. We will discuss the intersection of media and communication more in Chapter 16 “New Media and Communication”.

“Getting Real”

What Can You Do with a Degree in Communication Studies?

You’re hopefully already beginning to see that communication studies is a diverse and vibrant field of study. The multiple subfields and concentrations within the field allow for exciting opportunities for study in academic contexts but can create confusion and uncertainty when a person considers what they might do for their career after studying communication. It’s important to remember that not every college or university will have courses or concentrations in all the areas discussed next. Look at the communication courses offered at your school to get an idea of where the communication department on your campus fits into the overall field of study. Some departments are more general, offering students a range of courses to provide a well-rounded understanding of communication. Many departments offer concentrations or specializations within the major such as public relations, rhetoric, interpersonal communication, electronic media production, corporate communication. If you are at a community college and plan on transferring to another school, your choice of school may be determined by the course offerings in the department and expertise of the school’s communication faculty. It would be unfortunate for a student interested in public relations to end up in a department that focuses more on rhetoric or broadcasting, so doing your research ahead of time is key.

Since communication studies is a broad field, many students strategically choose a concentration and/or a minor that will give them an advantage in the job market. Specialization can definitely be an advantage, but don’t forget about the general skills you gain as a communication major. This book, for example, should help you build communication competence and skills in interpersonal communication, intercultural communication, group communication, and public speaking, among others. You can also use your school’s career services office to help you learn how to “sell” yourself as a communication major and how to translate what you’ve learned in your classes into useful information to include on your resume or in a job interview.

The main career areas that communication majors go into are business, public relations / advertising, media, nonprofit, government/law, and education. What Can I Do with This Major? “Communication Studies,” accessed May 18, 2012, http://whatcanidowiththismajor.com/major/communication-studies. Within each of these areas there are multiple career paths, potential employers, and useful strategies for success.

Business. Sales, customer service, management, real estate, human resources, training and development.

Public relations / advertising. Public relations, advertising/marketing, public opinion research, development, event coordination.

Media. Editing, copywriting, publishing, producing, directing, media sales, broadcasting.

Nonprofit. Administration, grant writing, fund-raising, public relations, volunteer coordination.

Government/law. City or town management, community affairs, lobbying, conflict negotiation / mediation.

Education. High school speech teacher, forensics/debate coach, administration and student support services, graduate school to further communication study.

Which of the areas listed above are you most interested in studying in school or pursuing as a career? Why?

What aspect(s) of communication studies does/do the department at your school specialize in? What concentrations/courses are offered?

Whether or not you are or plan to become a communication major, how do you think you could use what you have learned and will learn in this class to “sell” yourself on the job market?

Key Takeaways

Getting integrated: Communication is a broad field that draws from many academic disciplines. This interdisciplinary perspective provides useful training and experience for students that can translate into many career fields.

Communication is the process of generating meaning by sending and receiving symbolic cues that are influenced by multiple contexts.

There are five forms of communication: intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, public, and mass communication.

Intrapersonal communication is communication with oneself and occurs only inside our heads.

Interpersonal communication is communication between people whose lives mutually influence one another and typically occurs in dyads, which means in pairs.

Group communication occurs when three or more people communicate to achieve a shared goal.

Public communication is sender focused and typically occurs when one person conveys information to an audience.

Mass communication occurs when messages are sent to large audiences using print or electronic media.

Exercises

Getting integrated:

Over the course of a day, keep track of the forms of communication that you use. Make a pie chart of how much time you think you spend, on an average day, engaging in each form of communication (intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, public, and mass).

1.2 The Communication Process

Learning Objectives

Identify and define the components of the transmission model of communication.

Identify and define the components of the interaction model of communication.

Identify and define the components of the transaction model of communication.

Compare and contrast the three models of communication.

Use the transaction model of communication to analyze a recent communication encounter.

Communication is a complex process, and it is difficult to determine where or with whom a communication encounter starts and ends. Models of communication simplify the process by providing a visual representation of the various aspects of a communication encounter. Some models explain communication in more detail than others, but even the most complex model still doesn’t recreate what we experience in even a moment of a communication encounter. Models still serve a valuable purpose for students of communication because they allow us to see specific concepts and steps within the process of communication, define communication, and apply communication concepts. When you become aware of how communication functions, you can think more deliberately through your communication encounters, which can help you better prepare for future communication and learn from your previous communication. The three models of communication we will discuss are the transmission, interaction, and transaction models.

Although these models of communication differ, they contain some common elements. The first two models we will discuss, the transmission model and the interaction model, include the following parts: participants, messages, encoding, decoding, and channels. In communication models, the participants are the senders and/or receivers of messages in a communication encounter. The message is the verbal or nonverbal content being conveyed from sender to receiver. For example, when you say “Hello!” to your friend, you are sending a message of greeting that will be received by your friend.

The internal cognitive process that allows participants to send, receive, and understand messages is the encoding and decoding process. Encoding is the process of turning thoughts into communication. As we will learn later, the level of conscious thought that goes into encoding messages varies. Decoding is the process of turning communication into thoughts. For example, you may realize you’re hungry and encode the following message to send to your roommate: “I’m hungry. Do you want to get pizza tonight?” As your roommate receives the message, he decodes your communication and turns it back into thoughts in order to make meaning out of it. Of course, we don’t just communicate verbally—we have various options, or channels for communication. Encoded messages are sent through a channel, or a sensory route on which a message travels, to the receiver for decoding. While communication can be sent and received using any sensory route (sight, smell, touch, taste, or sound), most communication occurs through visual (sight) and/or auditory (sound) channels. If your roommate has headphones on and is engrossed in a video game, you may need to get his attention by waving your hands before you can ask him about dinner.

Transmission Model of Communication

The transmission model of communication describes communication as a linear, one-way process in which a sender intentionally transmits a message to a receiver. Richard Ellis and Ann McClintock, You Take My Meaning: Theory into Practice in Human Communication (London: Edward Arnold, 1990), 71. This model focuses on the sender and message within a communication encounter. Although the receiver is included in the model, this role is viewed as more of a target or end point rather than part of an ongoing process. We are left to presume that the receiver either successfully receives and understands the message or does not. The scholars who designed this model extended on a linear model proposed by Aristotle centuries before that included a speaker, message, and hearer. They were also influenced by the advent and spread of new communication technologies of the time such as telegraphy and radio, and you can probably see these technical influences within the model. Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver, The Mathematical Theory of Communication (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1949), 16. Think of how a radio message is sent from a person in the radio studio to you listening in your car. The sender is the radio announcer who encodes a verbal message that is transmitted by a radio tower through electromagnetic waves (the channel) and eventually reaches your (the receiver’s) ears via an antenna and speakers in order to be decoded. The radio announcer doesn’t really know if you receive his or her message or not, but if the equipment is working and the channel is free of static, then there is a good chance that the message was successfully received.

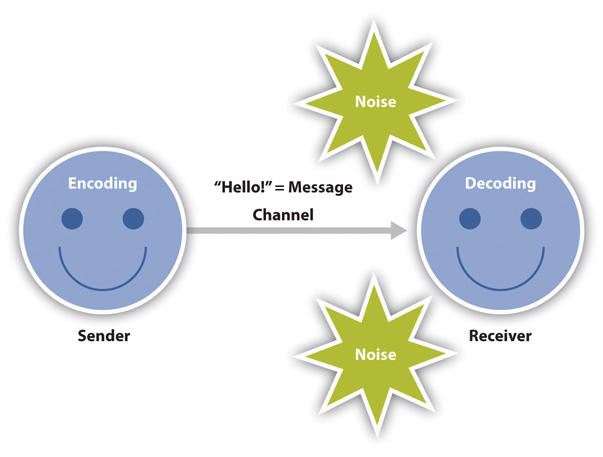

Figure 1.1 The Transmission Model of Communication

Since this model is sender and message focused, responsibility is put on the sender to help ensure the message is successfully conveyed. This model emphasizes clarity and effectiveness, but it also acknowledges that there are barriers to effective communication. Noise is anything that interferes with a message being sent between participants in a communication encounter. Even if a speaker sends a clear message, noise may interfere with a message being accurately received and decoded. The transmission model of communication accounts for environmental and semantic noise. Environmental noise is any physical noise present in a communication encounter. Other people talking in a crowded diner could interfere with your ability to transmit a message and have it successfully decoded. While environmental noise interferes with the transmission of the message, semantic noise refers to noise that occurs in the encoding and decoding process when participants do not understand a symbol. To use a technical example, FM antennae can’t decode AM radio signals and vice versa. Likewise, most French speakers can’t decode Swedish and vice versa. Semantic noise can also interfere in communication between people speaking the same language because many words have multiple or unfamiliar meanings.

Since this model is sender and message focused, responsibility is put on the sender to help ensure the message is successfully conveyed. This model emphasizes clarity and effectiveness, but it also acknowledges that there are barriers to effective communication. Noise is anything that interferes with a message being sent between participants in a communication encounter. Even if a speaker sends a clear message, noise may interfere with a message being accurately received and decoded. The transmission model of communication accounts for environmental and semantic noise. Environmental noise is any physical noise present in a communication encounter. Other people talking in a crowded diner could interfere with your ability to transmit a message and have it successfully decoded. While environmental noise interferes with the transmission of the message, semantic noise refers to noise that occurs in the encoding and decoding process when participants do not understand a symbol. To use a technical example, FM antennae can’t decode AM radio signals and vice versa. Likewise, most French speakers can’t decode Swedish and vice versa. Semantic noise can also interfere in communication between people speaking the same language because many words have multiple or unfamiliar meanings.

Although the transmission model may seem simple or even underdeveloped to us today, the creation of this model allowed scholars to examine the communication process in new ways, which eventually led to more complex models and theories of communication that we will discuss more later. This model is not quite rich enough to capture dynamic face-to-face interactions, but there are instances in which communication is one-way and linear, especially computer-mediated communication (CMC). As the following “Getting Plugged In” box explains, CMC is integrated into many aspects of our lives now and has opened up new ways of communicating and brought some new challenges. Think of text messaging for example. The transmission model of communication is well suited for describing the act of text messaging since the sender isn’t sure that the meaning was effectively conveyed or that the message was received at all. Noise can also interfere with the transmission of a text. If you use an abbreviation the receiver doesn’t know or the phone autocorrects to something completely different than you meant, then semantic noise has interfered with the message transmission. I enjoy bargain hunting at thrift stores, so I just recently sent a text to a friend asking if she wanted to go thrifting over the weekend. After she replied with “What?!?” I reviewed my text and saw that my “smart” phone had autocorrected thrifting to thrusting! You have likely experienced similar problems with text messaging, and a quick Google search for examples of text messages made funny or embarrassing by the autocorrect feature proves that many others do, too.

Interaction Model of Communication

The interaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending messages and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts. Wilbur Schramm, The Beginnings of Communication Study in America (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1997). Rather than illustrating communication as a linear, one-way process, the interaction model incorporates feedback, which makes communication a more interactive, two-way process. Feedback includes messages sent in response to other messages. For example, your instructor may respond to a point you raise during class discussion or you may point to the sofa when your roommate asks you where the remote control is. The inclusion of a feedback loop also leads to a more complex understanding of the roles of participants in a communication encounter. Rather than having one sender, one message, and one receiver, this model has two sender-receivers who exchange messages. Each participant alternates roles as sender and receiver in order to keep a communication encounter going. Although this seems like a perceptible and deliberate process, we alternate between the roles of sender and receiver very quickly and often without conscious thought.

The interaction model is also less message focused and more interaction focused. While the transmission model focused on how a message was transmitted and whether or not it was received, the interaction model is more concerned with the communication process itself. In fact, this model acknowledges that there are so many messages being sent at one time that many of them may not even be received. Some messages are also unintentionally sent. Therefore, communication isn’t judged effective or ineffective in this model based on whether or not a single message was successfully transmitted and received.

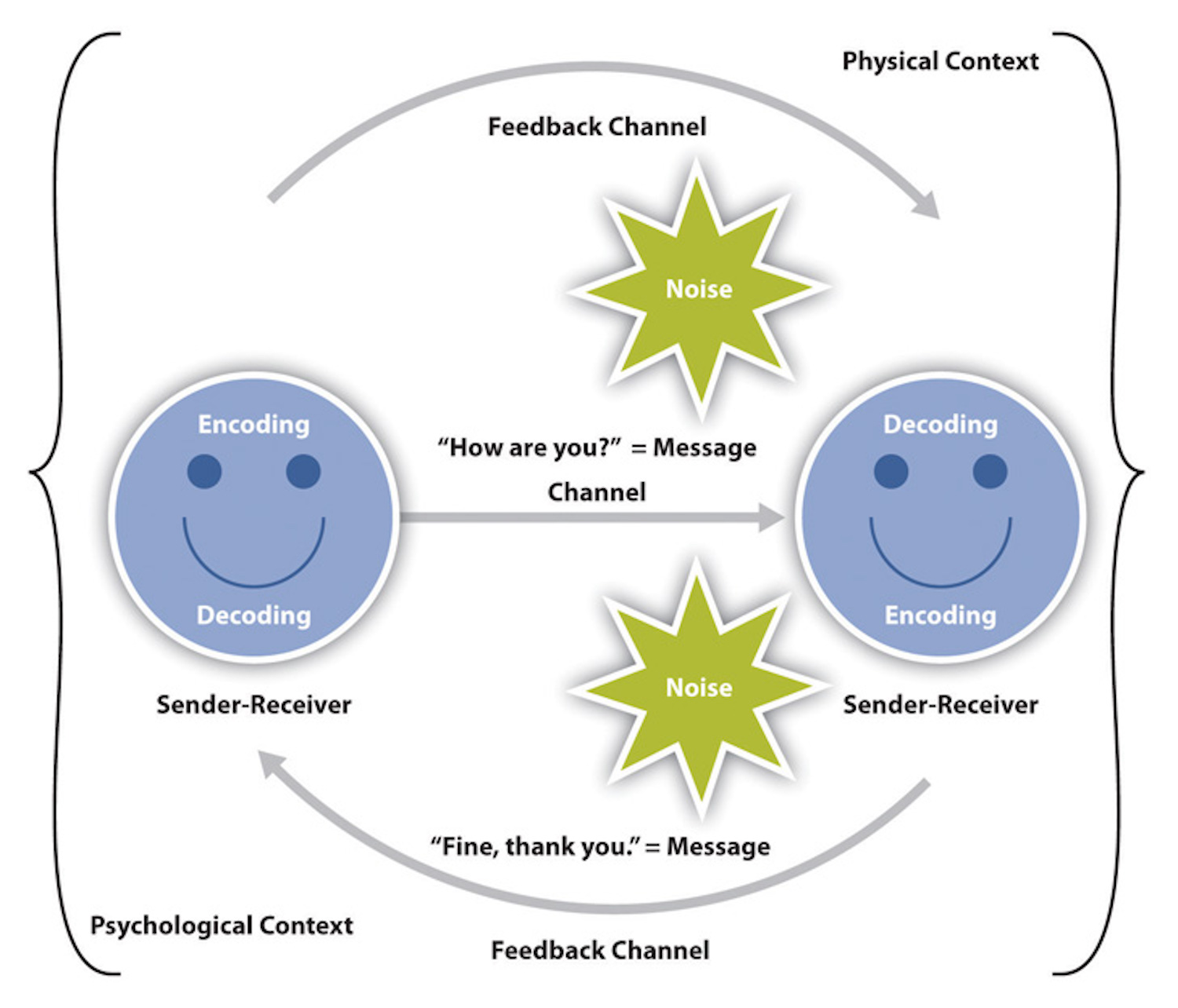

Figure 1.2 The Interaction Model of Communication

The interaction model takes physical and psychological context into account. Physical context includes the environmental factors in a communication encounter. The size, layout, temperature, and lighting of a space influence our communication. Imagine the different physical contexts in which job interviews take place and how that may affect your communication. I have had job interviews on a sofa in a comfortable office, sitting around a large conference table, and even once in an auditorium where I was positioned on the stage facing about twenty potential colleagues seated in the audience. I’ve also been walked around campus to interview with various people in temperatures below zero degrees. Although I was a little chilly when I got to each separate interview, it wasn’t too difficult to warm up and go on with the interview. During a job interview in Puerto Rico, however, walking around outside wearing a suit in near 90 degree temperatures created a sweating situation that wasn’t pleasant to try to communicate through. Whether it’s the size of the room, the temperature, or other environmental factors, it’s important to consider the role that physical context plays in our communication.

The interaction model takes physical and psychological context into account. Physical context includes the environmental factors in a communication encounter. The size, layout, temperature, and lighting of a space influence our communication. Imagine the different physical contexts in which job interviews take place and how that may affect your communication. I have had job interviews on a sofa in a comfortable office, sitting around a large conference table, and even once in an auditorium where I was positioned on the stage facing about twenty potential colleagues seated in the audience. I’ve also been walked around campus to interview with various people in temperatures below zero degrees. Although I was a little chilly when I got to each separate interview, it wasn’t too difficult to warm up and go on with the interview. During a job interview in Puerto Rico, however, walking around outside wearing a suit in near 90 degree temperatures created a sweating situation that wasn’t pleasant to try to communicate through. Whether it’s the size of the room, the temperature, or other environmental factors, it’s important to consider the role that physical context plays in our communication.

Psychological context includes the mental and emotional factors in a communication encounter. Stress, anxiety, and emotions are just some examples of psychological influences that can affect our communication. I recently found out some troubling news a few hours before a big public presentation. It was challenging to try to communicate because the psychological noise triggered by the stressful news kept intruding into my other thoughts. Seemingly positive psychological states, like experiencing the emotion of love, can also affect communication. During the initial stages of a romantic relationship individuals may be so “love struck” that they don’t see incompatible personality traits or don’t negatively evaluate behaviors they might otherwise find off-putting. Feedback and context help make the interaction model a more useful illustration of the communication process, but the transaction model views communication as a powerful tool that shapes our realities beyond individual communication encounters.

Transaction Model of Communication

As the study of communication progressed, models expanded to account for more of the communication process. Many scholars view communication as more than a process that is used to carry on conversations and convey meaning. We don’t send messages like computers, and we don’t neatly alternate between the roles of sender and receiver as an interaction unfolds. We also can’t consciously decide to stop communicating, because communication is more than sending and receiving messages. The transaction model differs from the transmission and interaction models in significant ways, including the conceptualization of communication, the role of sender and receiver, and the role of context. Dean C. Barnlund, “A Transactional Model of Communication,” in Foundations of Communication Theory, eds. Kenneth K. Sereno and C. David Mortensen (New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1970), 83–92.

To review, each model incorporates a different understanding of what communication is and what communication does. The transmission model views communication as a thing, like an information packet, that is sent from one place to another. From this view, communication is defined as sending and receiving messages. The interaction model views communication as an interaction in which a message is sent and then followed by a reaction (feedback), which is then followed by another reaction, and so on. From this view, communication is defined as producing conversations and interactions within physical and psychological contexts. The transaction model views communication as integrated into our social realities in such a way that it helps us not only understand them but also create and change them.

The transaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. In this model, we don’t just communicate to exchange messages; we communicate to create relationships, form intercultural alliances, shape our self-concepts, and engage with others in dialogue to create communities. In short, we don’t communicate about our realities; communication helps to construct our realities.

The roles of sender and receiver in the transaction model of communication differ significantly from the other models. Instead of labeling participants as senders and receivers, the people in a communication encounter are referred to as communicators. Unlike the interaction model, which suggests that participants alternate positions as sender and receiver, the transaction model suggests that we are simultaneously senders and receivers. For example, on a first date, as you send verbal messages about your interests and background, your date reacts nonverbally. You don’t wait until you are done sending your verbal message to start receiving and decoding the nonverbal messages of your date. Instead, you are simultaneously sending your verbal message and receiving your date’s nonverbal messages. This is an important addition to the model because it allows us to understand how we are able to adapt our communication—for example, a verbal message—in the middle of sending it based on the communication we are simultaneously receiving from our communication partner.

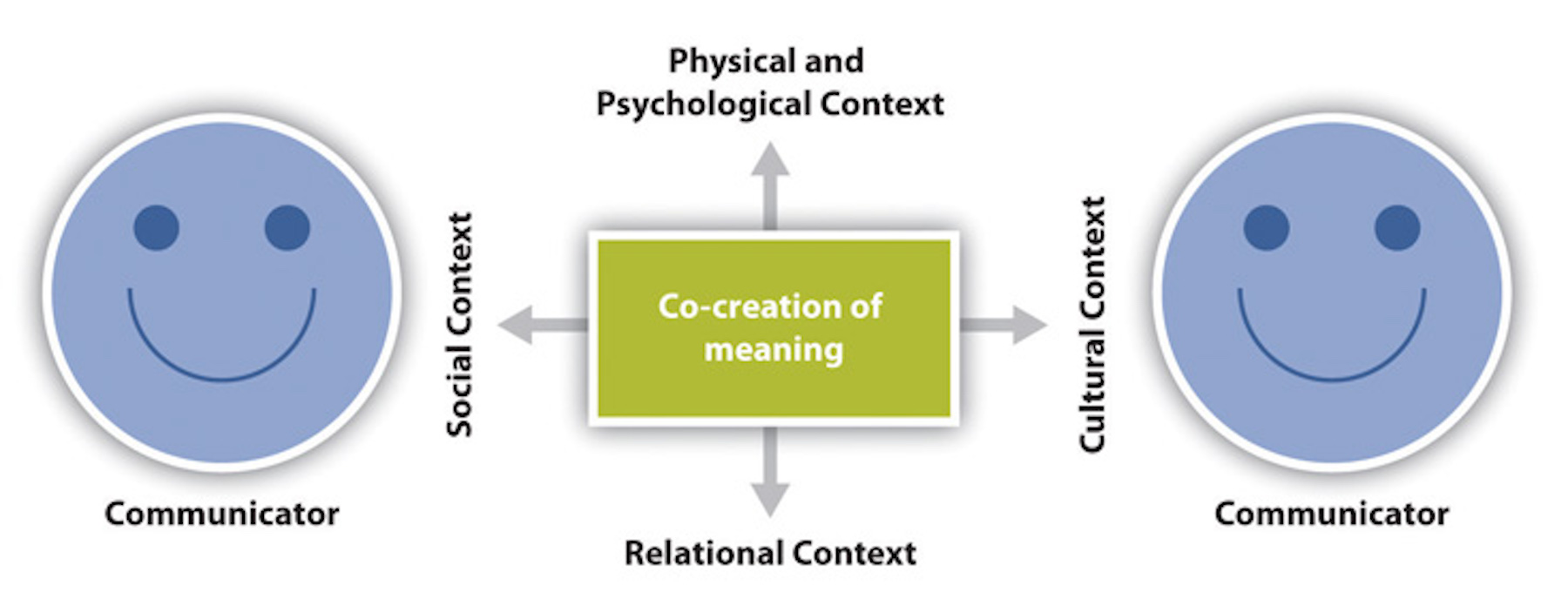

Figure 1.3 The Transaction Model of Communication

The transaction model also includes a more complex understanding of context. The interaction model portrays context as physical and psychological influences that enhance or impede communication. While these contexts are important, they focus on message transmission and reception. Since the transaction model of communication views communication as a force that shapes our realities before and after specific interactions occur, it must account for contextual influences outside of a single interaction. To do this, the transaction model considers how social, relational, and cultural contexts frame and influence our communication encounters.

The transaction model also includes a more complex understanding of context. The interaction model portrays context as physical and psychological influences that enhance or impede communication. While these contexts are important, they focus on message transmission and reception. Since the transaction model of communication views communication as a force that shapes our realities before and after specific interactions occur, it must account for contextual influences outside of a single interaction. To do this, the transaction model considers how social, relational, and cultural contexts frame and influence our communication encounters.

Social context refers to the stated rules or unstated norms that guide communication. As we are socialized into our various communities, we learn rules and implicitly pick up on norms for communicating. Some common rules that influence social contexts include don’t lie to people, don’t interrupt people, don’t pass people in line, greet people when they greet you, thank people when they pay you a compliment, and so on. Parents and teachers often explicitly convey these rules to their children or students. Rules may be stated over and over, and there may be punishment for not following them.

Norms are social conventions that we pick up on through observation, practice, and trial and error. We may not even know we are breaking a social norm until we notice people looking at us strangely or someone corrects or teases us. For example, as a new employee you may over- or underdress for the company’s holiday party because you don’t know the norm for formality. Although there probably isn’t a stated rule about how to dress at the holiday party, you will notice your error without someone having to point it out, and you will likely not deviate from the norm again in order to save yourself any potential embarrassment. Even though breaking social norms doesn’t result in the formal punishment that might be a consequence of breaking a social rule, the social awkwardness we feel when we violate social norms is usually enough to teach us that these norms are powerful even though they aren’t made explicit like rules. Norms even have the power to override social rules in some situations. To go back to the examples of common social rules mentioned before, we may break the rule about not lying if the lie is meant to save someone from feeling hurt. We often interrupt close friends when we’re having an exciting conversation, but we wouldn’t be as likely to interrupt a professor while they are lecturing. Since norms and rules vary among people and cultures, relational and cultural contexts are also included in the transaction model in order to help us understand the multiple contexts that influence our communication.

Relational context includes the previous interpersonal history and type of relationship we have with a person. We communicate differently with someone we just met versus someone we’ve known for a long time. Initial interactions with people tend to be more highly scripted and governed by established norms and rules, but when we have an established relational context, we may be able to bend or break social norms and rules more easily. For example, you would likely follow social norms of politeness and attentiveness and might spend the whole day cleaning the house for the first time you invite your new neighbors to visit. Once the neighbors are in your house, you may also make them the center of your attention during their visit. If you end up becoming friends with your neighbors and establishing a relational context, you might not think as much about having everything cleaned and prepared or even giving them your whole attention during later visits. Since communication norms and rules also vary based on the type of relationship people have, relationship type is also included in relational context. For example, there are certain communication rules and norms that apply to a supervisor-supervisee relationship that don’t apply to a brother-sister relationship and vice versa. Just as social norms and relational history influence how we communicate, so does culture.

Cultural context includes various aspects of identities such as race, gender, nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, and ability. We will learn more about these identities in Chapter 2 “Communication and Perception”, but for now it is important for us to understand that whether we are aware of it or not, we all have multiple cultural identities that influence our communication. Some people, especially those with identities that have been historically marginalized, are regularly aware of how their cultural identities influence their communication and influence how others communicate with them. Conversely, people with identities that are dominant or in the majority may rarely, if ever, think about the role their cultural identities play in their communication.

When cultural context comes to the forefront of a communication encounter, it can be difficult to manage. Since intercultural communication creates uncertainty, it can deter people from communicating across cultures or lead people to view intercultural communication as negative. But if you avoid communicating across cultural identities, you will likely not get more comfortable or competent as a communicator. Difference, as we will learn in Chapter 8, isn’t a bad thing. In fact, intercultural communication has the potential to enrich various aspects of our lives. In order to communicate well within various cultural contexts, it is important to keep an open mind and avoid making assumptions about others’ cultural identities. While you may be able to identify some aspects of the cultural context within a communication encounter, there may also be cultural influences that you can’t see. A competent communicator shouldn’t assume to know all the cultural contexts a person brings to an encounter, since not all cultural identities are visible. As with the other contexts, it requires skill to adapt to shifting contexts, and the best way to develop these skills is through practice and reflection.

Key Takeaways

Communication models are not complex enough to truly capture all that takes place in a communication encounter, but they can help us examine the various steps in the process in order to better understand our communication and the communication of others.

The interaction model of communication describes communication as a two-way process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts. This model captures the interactive aspects of communication but still doesn’t account for how communication constructs our realities and is influenced by social and cultural contexts.

The transaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. This model includes participants who are simultaneously senders and receivers and accounts for how communication constructs our realities, relationships, and communities.

Exercises

Getting integrated:

How might knowing the various components of the communication process help you in your academic life, your professional life, and your civic life?

Use the transaction model or interaction model of communication to analyze a recent communication encounter you had. Sketch out the communication encounter and make sure to label each part of the model (communicators or sender-receiver; message; channel; feedback; noise; and physical, psychological, social, relational, and cultural contexts).

1.3 Communication Principles

Learning Objectives

Discuss how communication is integrated in various aspects of your life.

Explain how the notion of a “process” fits into communication.

Discuss the ways in which communication is guided by culture and context.

Taking this course will change how you view communication. Most people admit that communication is important, but it’s often in the back of our minds or viewed as something that “just happens.” Putting communication at the front of your mind and becoming more aware of how you communicate can be informative and have many positive effects. When I first started studying communication as an undergraduate, I began seeing the concepts we learned in class in my everyday life. When I worked in groups, I was able to apply what I had learned about group communication to improve my performance and overall experience. I also noticed interpersonal concepts and theories as I communicated within various relationships. Whether I was analyzing mediated messages or considering the ethical implications of a decision before I made it, studying communication allowed me to see more of what was going on around me, which allowed me to more actively and competently participate in various communication contexts. In this section, as we learn the principles of communication, I encourage you to take note of aspects of communication that you haven’t thought about before and begin to apply the principles of communication to various parts of your life.

Communication Is Integrated into All Parts of Our Lives

This book is meant to help people see the value of communication in the real world and in our real lives. When I say real, I don’t mean to imply that there is some part of our world or lives that is not real. Since communication is such a practical field of study, I use the word real to emphasize that what you’re reading in this book isn’t just about theories and vocabulary or passing a test and giving a good speech. I also don’t mean to imply that there is a divide between the classroom and the real world. The “real world” is whatever we are experiencing at any given moment. In order to explore how communication is integrated into all parts of our lives, I have divided up our lives into four spheres: academic, professional, personal, and civic. The boundaries and borders between these spheres are not solid, and there is much overlap. After all, much of what goes on in a classroom is present in a professional environment, and the classroom has long been seen as a place to prepare students to become active and responsible citizens in their civic lives. The philosophy behind this approach is called integrative learning, which encourages students to reflect on how the content they are learning connects to other classes they have taken or are taking, their professional goals, and their civic responsibilities.

Academic

It’s probably not difficult to get you, as students in a communication class, to see the relevance of communication to your academic lives. At least during this semester, studying communication is important to earn a good grade in the class, right? Beyond the relevance to your grade in this class, I challenge you to try to make explicit connections between this course and courses you have taken before and are currently taking. Then, when you leave this class, I want you to connect the content in future classes back to what you learned here. If you can begin to see these connections now, you can build on the foundational communication skills you learn in here to become a more competent communicator, which will undoubtedly also benefit you as a student.

Aside from wanting to earn a good grade in this class, you may also be genuinely interested in becoming a better communicator. If that’s the case, you are in luck because research shows that even people who have poor communication skills can improve a wide range of verbal, nonverbal, and interpersonal communication skills by taking introductory communication courses. Wendy S. Zabava and Andrew D. Wolvin, “The Differential Impact of a Basic Communication Course on Perceived Communication Competencies in Class, Work, and Social Contexts,” Communication Education 42 (1993): 215–17. Communication skills are also tied to academic success. Poor listening skills were shown to contribute significantly to failure in a person’s first year of college. Also, students who take a communication course report more confidence in their communication abilities, and these students have higher grade point averages and are less likely to drop out of school. Much of what we do in a classroom—whether it is the interpersonal interactions with our classmates and professor, individual or group presentations, or listening—is discussed in this textbook and can be used to build or add to a foundation of good communication skills and knowledge that can carry through to other contexts.

Professional

The National Association of Colleges and Employers has found that employers most desire good communication skills in the college graduates they may hire. National Association of Colleges and Employers, Job Outlook 2011 (2010): 25. Desired communication skills vary from career to career, but again, this textbook provides a foundation onto which you can build communication skills specific to your major or field of study. Research has shown that introductory communication courses provide important skills necessary for functioning in entry-level jobs, including listening, writing, motivating/persuading, interpersonal skills, informational interviewing, and small-group problem solving. Vincent S. DiSalvo, “A Summary of Current Research Identifying Communication Skills in Various Organizational Contexts,” Communication Education 29 (1980): 283–90. Interpersonal communication skills are also highly sought after by potential employers, consistently ranking in the top ten in national surveys. National Association of Colleges and Employers, Job Outlook 2011 (2010): 25. Poor listening skills, lack of conciseness, and inability to give constructive feedback have been identified as potential communication challenges in professional contexts. Employers appreciate good listening skills and the ability to communicate concisely because efficiency and clarity are often directly tied to productivity and success in terms of profit or task/project completion. Despite the well-documented need for communication skills in the professional world, many students still resist taking communication classes. Perhaps people think they already have good communication skills or can improve their skills on their own. While either of these may be true for some, studying communication can only help. In such a competitive job market, being able to document that you have received communication instruction and training from communication professionals (the faculty in your communication department) can give you the edge needed to stand out from other applicants or employees.

Personal

While many students know from personal experience and from the prevalence of communication counseling on television talk shows and in self-help books that communication forms, maintains, and ends our interpersonal relationships, they do not know the extent to which that occurs. I am certain that when we get to the interpersonal communication chapters in this textbook that you will be intrigued and maybe even excited by the relevance and practicality of the concepts and theories discussed there. My students often remark that they already know from experience much of what’s discussed in the interpersonal unit of the course. While we do learn from experience, until we learn specific vocabulary and develop foundational knowledge of communication concepts and theories, we do not have the tools needed to make sense of these experiences. Just having a vocabulary to name the communication phenomena in our lives increases our ability to consciously alter our communication to achieve our goals, avoid miscommunication, and analyze and learn from our inevitable mistakes. Once we get further into the book, I am sure the personal implications of communication will become very clear.

Civic

The connection between communication and our civic lives is a little more abstract and difficult for students to understand. Many younger people don’t yet have a conception of a “civic” part of their lives because the academic, professional, and personal parts of their lives have so much more daily relevance. Civic engagement refers to working to make a difference in our communities by improving the quality of life of community members; raising awareness about social, cultural, or political issues; or participating in a wide variety of political and nonpolitical processes. Thomas Ehrlich, Civic Responsibility and Higher Education (Phoenix, AZ: Oryx, 2000), vi. The civic part of our lives is developed through engagement with the decision making that goes on in our society at the small-group, local, state, regional, national, or international level. Such involvement ranges from serving on a neighborhood advisory board to sending an e-mail to a US senator. Discussions and decisions that affect our communities happen around us all the time, but it takes time and effort to become a part of that process. Doing so, however, allows us to become a part of groups or causes that are meaningful to us, which enables us to work for the common good. This type of civic engagement is crucial to the functioning of a democratic society.

Communication scholars have been aware of the connections between communication and a person’s civic engagement or citizenship for thousands of years. Aristotle, who wrote the first and most influential comprehensive book on communication 2,400 years ago, taught that it is through our voice, our ability to communicate, that we engage with the world around us, participate in our society, and become a “virtuous citizen.” It is a well-established and unfortunate fact that younger people, between the ages of eighteen and thirty, are some of the least politically active and engaged members of our democracy. Civic engagement includes but goes beyond political engagement, which includes things like choosing a political party or advocating for a presidential candidate. Although younger people have tended not to be as politically engaged as other age groups, the current generation of sixteen- to twenty-nine-year-olds, known as the millennial generation, is known to be very engaged in volunteerism and community service. In addition, some research has indicated that college students are eager for civic engagement but are not finding the resources they need on their campuses. Scott Jaschik, “The Civic Engagement Gap,” Inside Higher Ed, September 30, 2009, accessed May 18, 2012, http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/09/30/civic. The American Association of Colleges and Universities has launched several initiatives and compiled many resources for students and faculty regarding civic engagement. I encourage you to explore their website at the following link and try to identify some ways in which you can productively integrate what you are learning in this class into a civic context: http://www.aacu.org/resources/civic-learning.

Communication Is a Process

Communication is a process that involves an interchange of verbal and/or nonverbal messages within a continuous and dynamic sequence of events. Owen Hargie, Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (London: Routledge, 2011), 15. When we refer to communication as a process, we imply that it doesn’t have a distinct beginning and end or follow a predetermined sequence of events. It can be difficult to trace the origin of a communication encounter, since communication doesn’t always follow a neat and discernible format, which makes studying communication interactions or phenomena difficult. Any time we pull one part of the process out for study or closer examination, we artificially “freeze” the process in order to examine it, which is not something that is possible when communicating in real life. But sometimes scholars want to isolate a particular stage in the process in order to gain insight by studying, for example, feedback or eye contact. Doing that changes the very process itself, and by the time you have examined a particular stage or component of the process, the entire process may have changed. These snapshots are useful for scholarly interrogation of the communication process, and they can also help us evaluate our own communication practices, troubleshoot a problematic encounter we had, or slow things down to account for various contexts before we engage in communication. Frank E. X. Dance and Carl E. Larson, The Functions of Human Communication: A Theoretical Approach (New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, 1976), 28.

We have already learned, in the transaction model of communication, that we communicate using multiple channels and send and receive messages simultaneously. There are also messages and other stimuli around us that we never actually perceive because we can only attend to so much information at one time. The dynamic nature of communication allows us to examine some principles of communication that are related to its processual nature. Next, we will learn that communication messages vary in terms of their level of conscious thought and intention, communication is irreversible, and communication is unrepeatable.

Some scholars have put forth definitions of communication stating that messages must be intended for others to perceive them in order for a message to “count” as communication. This narrow definition only includes messages that are tailored or at least targeted to a particular person or group and excludes any communication that is involuntary. Frank E. X. Dance and Carl E. Larson, The Functions of Human Communication: A Theoretical Approach (New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, 1976), 25. Since intrapersonal communication happens in our heads and isn’t intended for others to perceive, it wouldn’t be considered communication. But imagine the following scenario: You and I are riding on a bus and you are sitting across from me. As I sit thinking about a stressful week ahead, I wrinkle up my forehead, shake my head, and put my head in my hands. Upon seeing this you think, “That guy must be pretty stressed out.” In this scenario, did communication take place? If I really didn’t intend for anyone to see the nonverbal communication that went along with my intrapersonal communication, then this definition would say no. But even though words weren’t exchanged, you still generated meaning from the communication I was unintentionally sending. As a communication scholar, I do not take such a narrow definition of communication. Based on the definition of communication from the beginning of this chapter, the scenario we just discussed would count as communication, but the scenario illustrates the point that communication messages are sent both intentionally and unintentionally.

Communication messages also vary in terms of the amount of conscious thought that goes into their creation. In general, we can say that intentional communication usually includes more conscious thought and unintentional communication usually includes less. For example, some communication is reactionary and almost completely involuntary. We often scream when we are frightened, say “ouch!” when we stub our toe, and stare blankly when we are bored. This isn’t the richest type of communication, but it is communication. Some of our interactions are slightly more substantial and include more conscious thought but are still very routine. For example, we say “excuse me” when we need to get past someone, say “thank you” when someone holds the door for us, or say “what’s up?” to our neighbor we pass every day in the hall. The reactionary and routine types of communication just discussed are common, but the messages most studied by communication scholars are considered constructed communication. These messages include more conscious thought and intention than reactionary or routine messages and often go beyond information exchange to also meet relational and identity needs. As we will learn later on, a higher degree of conscious thought and intention doesn’t necessarily mean the communication will be effective, understood, or ethical. In addition, ethical communicators cannot avoid responsibility for the effects of what they say by claiming they didn’t “intend” for their communication to cause an undesired effect. Communication has short- and long-term effects, which illustrates the next principle we will discuss—communication is irreversible.

The dynamic nature of the communication process also means that communication is irreversible. After an initial interaction has gone wrong, characters in sitcoms and romantic comedies often use the line “Can we just start over?” As handy as it would be to be able to turn the clock back and “redo” a failed or embarrassing communication encounter, it is impossible. Miscommunication can occur regardless of the degree of conscious thought and intention put into a message. For example, if David tells a joke that offends his coworker Beth, then he can’t just say, “Oh, forget I said that,” or “I didn’t intend for it to be offensive.” The message has been sent and it can’t be taken back. I’m sure we have all wished we could take something back that we have said. Conversely, when communication goes well, we often wish we could recreate it. However, in addition to communication being irreversible, it is also unrepeatable.

If you try to recreate a good job interview experience by asking the same questions and telling the same stories about yourself, you can’t expect the same results. Even trying to repeat a communication encounter with the same person won’t feel the same or lead to the same results. We have already learned the influence that contexts have on communication, and those contexts change frequently. Even if the words and actions stay the same, the physical, psychological, social, relational, and cultural contexts will vary and ultimately change the communication encounter. Have you ever tried to recount a funny or interesting experience to a friend who doesn’t really seem that impressed? These “I guess you had to be there” moments illustrate the fact that communication is unrepeatable.

Content and Relationship in the Communication Process

Related to the process nature of communication is the principle that all communication contains content and relationship dimensions (Watzlavick, Beavin, and Jackson, 1967). Content is what the communication conveys, typically the idea that is being directly stated. This dimension is usually communicated in words. A more subtle message is also conveyed every time we communicate. The relationship dimension is how we view our connection with the person to whom we are communicating, and it is usually conveyed indirectly, in how we communicate. We may verbalize the relationship dimension by saying, “You’re my best friend,” or “I love you, man.” More often we convey this nonverbally, through our tone of voice, our facial expression, or our posture and gesture. We may also convey this in our word choice and phrasing.

According to this principle, as we exchange messages at a content level, these relationship messages are also sent and received. Therefore, our relationships are constantly in a state of negotiation: being developed, defined, changed, or reaffirmed in every moment of communication. In order to understand and be successful in relationships, we must negotiate both content and relationship meanings.

While there are many kinds of relationship messages, three key relationship dimensions are often negotiated on the relationship level — dominance, affection, and involvement (Watson and Brodowsky, 2004). These are expressed as points on a continuum, from asserting control to giving up control, from liking to disliking, and from being familiar to being unacquainted.

Recognizing relationship messages

Here are three descriptions of messages. Identify possible relationship messages based on how the messages fit the three relationship dimensions. Where would you place each message based on the continua — from asserting control to giving up control, from liking to disliking, and from being familiar to being unacquainted:

- Parent to child — “You are not leaving this house until you clean your room.”

- Older brother to younger sibling — “Let’s go shoot some hoops. I want to see how your pathetic jump shot is coming along.”

- On a first date –“I don’t care what movie we see. I’m not particular. What do you want to see?”

References

Watson, K., & Brodowsky, G. H. (2004). Achieving content and relational communication goals: A model of media choice. Paper presented at The Academy of Management National Meeting.

Watzlawick, P., Bavelas. J. B., and Jackson, D. D. (1967). Pragmatics of Human Communication: A Study of Interactional Patterns, Pathologies, and Paradoxes. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

[This textbox was written by Tony Arduini in 2019 and is shared via Creative Commons Share-alike license 3.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/]

Communication Is Guided by Culture and Context

As we learned earlier, context is a dynamic component of the communication process. Culture and context also influence how we perceive and define communication. Western culture tends to put more value on senders than receivers and on the content rather the context of a message. These cultural values are reflected in our definitions and models of communication. As we will learn in later chapters, cultures vary in terms of having a more individualistic or more collectivistic cultural orientation. The United States is considered an individualistic culture, where emphasis is put on individual expression and success. Japan is considered a collectivistic culture, where emphasis is put on group cohesion and harmony. These are strong cultural values that are embedded in how we learn to communicate. In many collectivistic cultures, there is more emphasis placed on silence and nonverbal context. Whether in the United States, Japan, or another country, people are socialized from birth to communication in culturally specific ways that vary by context. In this section we will discuss how communication is learned, the rules and norms that influence how we communicate, and the ethical implications of communication.

Communication Is Learned

Most people are born with the capacity and ability to communicate, but everyone communicates differently. This is because communication is learned rather than innate. As we have already seen, communication patterns are relative to the context and culture in which one is communicating, and many cultures have distinct languages consisting of symbols.

A key principle of communication is that it is symbolic. Communication is symbolic in that the words that make up our language systems do not directly correspond to something in reality. Instead, they stand in for or symbolize something. The fact that communication varies so much among people, contexts, and cultures illustrates the principle that meaning is not inherent in the words we use. For example, let’s say you go to France on vacation and see the word poisson on the menu. Unless you know how to read French, you will not know that the symbol is the same as the English symbol fish. Those two words don’t look the same at all, yet they symbolize the same object. If you went by how the word looks alone, you might think that the French word for fish is more like the English word poison and avoid choosing that for your dinner. Putting a picture of a fish on a menu would definitely help a foreign tourist understand what they are ordering, since the picture is an actual representation of the object rather than a symbol for it.

All symbolic communication is learned, negotiated, and dynamic. We know that the letters b-o-o-k refer to a bound object with multiple written pages. We also know that the letters t-r-u-c-k refer to a vehicle with a bed in the back for hauling things. But if we learned in school that the letters t-r-u-c-k referred to a bound object with written pages and b-o-o-k referred to a vehicle with a bed in the back, then that would make just as much sense, because the letters don’t actually refer to the object and the word itself only has the meaning that we assign to it. We will learn more, in Chapter 3 “Verbal Communication”, about how language works, but communication is more than the words we use.

We are all socialized into different languages, but we also speak different “languages” based on the situation we are in. For example, in some cultures it is considered inappropriate to talk about family or health issues in public, but it wouldn’t be odd to overhear people in a small town grocery store in the United States talking about their children or their upcoming surgery. There are some communication patterns shared by very large numbers of people and some that are particular to a dyad—best friends, for example, who have their own inside terminology and expressions that wouldn’t make sense to anyone else. These examples aren’t on the same scale as differing languages, but they still indicate that communication is learned. They also illustrate how rules and norms influence how we communicate.

Rules and Norms

Earlier we learned about the transaction model of communication and the powerful influence that social context and the roles and norms associated with social context have on our communication. Whether verbal or nonverbal, mediated or interpersonal, our communication is guided by rules and norms.

Phatic communion is an instructive example of how we communicate under the influence of rules and norms. Gunter Senft, “Phatic Communion,” in Culture and Language Use, eds. Gunter Senft, Jan-Ola Ostman, and Jef Verschueren (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2009), 226–33. Phatic communion refers to scripted and routine verbal interactions that are intended to establish social bonds rather than actually exchange meaning. When you pass your professor in the hall, the exchange may go as follows:

| Student: | “Hey, how are you?” |

| Professor: | “Fine, how are you?” |

| Student: | “Fine.” |

What is the point of this interaction? It surely isn’t to actually inquire as to each other’s well-being. We have similar phatic interactions when we make comments on the weather or the fact that it’s Monday. We often joke about phatic communion because we see that is pointless, at least on the surface. The student and professor might as well just pass each other in the hall and say the following to each other:

| Student: | “Generic greeting question.” |

| Professor: | “Generic greeting response and question.” |

| Student: | “Generic response.” |

This is an example of communication messages that don’t really require a high level of conscious thought or convey much actual content or generate much meaning. So if phatic communion is so “pointless,” why do we do it?

The term phatic communion derives from the Greek word phatos, which means “spoken,” and the word communion, which means “connection or bond.” As we discussed earlier, communication helps us meet our relational needs. In addition to finding communion through food or religion, we also find communion through our words. But the degree to which and in what circumstances we engage in phatic communion is also influenced by norms and rules. Generally, US Americans find silence in social interactions awkward, which is one sociocultural norm that leads to phatic communion, because we fill the silence with pointless words to meet the social norm. It is also a norm to greet people when you encounter them, especially if you know them. We all know not to unload our physical and mental burdens on the person who asks, “How are you?” or go through our “to do” list with the person who asks, “What’s up?” Instead, we conform to social norms through this routine type of verbal exchange.

Phatic communion, like most aspects of communication we will learn about, is culturally relative as well. While most cultures engage in phatic communion, the topics of and occasions for phatic communion vary. Scripts for greetings in the United States are common, but scripts for leaving may be more common in another culture. Asking about someone’s well-being may be acceptable phatic communion in one culture, and asking about the health of someone’s family may be more common in another.

Communication Has Ethical Implications

Another culturally and situationally relative principle of communication is the fact that communication has ethical implications. Communication ethics deals with the process of negotiating and reflecting on our actions and communication regarding what we believe to be right and wrong. Aristotle said, “In the arena of human life the honors and rewards fall to those who show their good qualities in action.” Judy C. Pearson, Jeffrey T. Child, Jody L. Mattern, and David H. Kahl Jr., “What Are Students Being Taught about Ethics in Public Speaking Textbooks?” Communication Quarterly 54, no. 4 (2006): 508. Aristotle focuses on actions, which is an important part of communication ethics. While ethics has been studied as a part of philosophy since the time of Aristotle, only more recently has it become applied. In communication ethics, we are more concerned with the decisions people make about what is right and wrong than the systems, philosophies, or religions that inform those decisions. Much of ethics is gray area. Although we talk about making decisions in terms of what is right and what is wrong, the choice is rarely that simple. Aristotle goes on to say that we should act “to the right extent, at the right time, with the right motive, and in the right way.” This quote connects to communication competence, which focuses on communicating effectively and appropriately and will be discussed more in Section 1.4 “Communication Competence”.

Communication has broad ethical implications. Later in this book we will discuss the importance of ethical listening, how to avoid plagiarism, how to present evidence ethically, and how to apply ethical standards to mass media and social media. These are just a few examples of how communication and ethics will be discussed in this book, but hopefully you can already see that communication ethics is integrated into academic, professional, personal, and civic contexts.