Chapter 11 – Informative and Persuasive Speaking

Communicative messages surround us. Most try to teach us something and/or influence our thoughts or behaviors. As with any type of communication, some messages are more engaging and effective than others. I’m sure you have experienced the displeasure of sitting through a boring class lecture that didn’t seem to relate to your interests or a lecture so packed with information that your brain felt overloaded. Likewise, you have probably been persuaded by a message only to find out later that the argument that persuaded you was faulty or the speaker misleading. As senders and receivers of messages, it’s important that we be able to distinguish between informative and persuasive messages and know how to create and deliver them.

11.1 Informative Speeches

Learning Objectives

Identify common topic categories for informative speeches.

Identify strategies for researching and supporting informative speeches.

Explain the different methods of informing.

Employ strategies for effective informative speaking, including avoiding persuasion, avoiding information overload, and engaging the audience.

Many people would rather go see an impassioned political speech or a comedic monologue than a lecture. Although informative speaking may not be the most exciting form of public speaking, it is the most common. Reports, lectures, training seminars, and demonstrations are all examples of informative speaking. That means you are more likely to give and listen to informative speeches in a variety of contexts. Some organizations, like consulting firms, and career fields, like training and development, are solely aimed at conveying information. College alumni have reported that out of many different speech skills, informative speaking is most important. Rudolph Verderber, Essentials of Informative Speaking: Theory and Contexts (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1991), 3. Since your exposure to informative speaking is inevitable, why not learn how to be a better producer and consumer of informative messages?

Creating an Informative Speech

As you’ll recall from Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech”, speaking to inform is one of the three possible general purposes for public speaking. The goal of informative speaking is to teach an audience something using objective factual information. Interestingly, informative speaking is a newcomer in the world of public speaking theorizing and instruction, which began thousands of years ago with the ancient Greeks. Thomas H. Olbricht, Informative Speaking (Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, 1968), 1–12. Ancient philosophers and statesmen like Aristotle, Cicero, and Quintilian conceived of public speaking as rhetoric, which is inherently persuasive. During that time, and until the 1800s, almost all speaking was argumentative. Teaching and instruction were performed as debates, and even fields like science and medicine relied on argumentative reasoning instead of factual claims.

While most instruction is now verbal, for most of modern history, people learned by doing rather than listening, as apprenticeships were much more common than classroom-based instruction. So what facilitated the change from argumentative and demonstrative teaching to verbal and informative teaching? One reason for this change was the democratization of information. Technical information used to be jealously protected by individuals, families, or guilds. Now society generally believes that information should be shared and made available to all. The increasing complexity of fields of knowledge and professions also increased the need for informative speaking. Now one must learn a history or backstory before actually engaging with a subject or trade. Finally, much of the information that has built up over time has become commonly accepted; therefore much of the history or background information isn’t disputed and can now be shared in an informative rather than argumentative way.

Choosing an Informative Speech Topic

Being a successful informative speaker starts with choosing a topic that can engage and educate the audience. Your topic choices may be influenced by the level at which you are speaking. Informative speaking usually happens at one of three levels: formal, vocational, and impromptu. Rudolph Verderber, Essentials of Informative Speaking: Theory and Contexts (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1991), 3–4. Formal informative speeches occur when an audience has assembled specifically to hear what you have to say. Being invited to speak to a group during a professional meeting, a civic gathering, or a celebration gala brings with it high expectations. Only people who have accomplished or achieved much are asked to serve as keynote speakers, and they usually speak about these experiences. Many more people deliver informative speeches at the vocational level, as part of their careers. Teachers like me spend many hours lecturing, which is a common form of informative speaking. In addition, human resources professionals give presentations about changes in policy and provide training for new employees, technicians in factories convey machine specifications and safety procedures, and servers describe how a dish is prepared in their restaurant. Last, we all convey information daily in our regular interactions. When we give a freshman directions to a campus building, summarize the latest episode of American Idol for our friend who missed it, or explain a local custom to an international student, we are engaging in impromptu informative speaking.

Whether at the formal, vocational, or impromptu level, informative speeches can emerge from a range of categories, which include objects, people, events, processes, concepts, and issues. An extended speech at the formal level may include subject matter from several of these categories, while a speech at the vocational level may convey detailed information about a process, concept, or issue relevant to a specific career.

Since we don’t have time to research or organize content for impromptu informative speaking, these speeches may provide a less detailed summary of a topic within one of these categories. A broad informative speech topic could be tailored to fit any of these categories. As you draft your specific purpose and thesis statements, think about which category or categories will help you achieve your speech goals, and then use it or them to guide your research. Table 10.1 “Sample Informative Speech Topics by Category” includes an example of how a broad informative subject area like renewable energy can be adapted to each category as well as additional sample topics.

Table 11.1 Sample Informative Speech Topics by Category

|

Category |

Renewable Energy Example |

Other Examples |

| Objects | Biomass gasifier | Tarot cards, star-nosed moles, Enterprise 1701-D |

| People | Al Gore | Jennifer Lopez, Bayard Rustin, the Amish |

| Concepts | Sustainability | Machismo, intuition, Wa (social harmony) |

| Events | Earth Day | Pi Day, Take Back the Night, 2012 presidential election |

| Processes | Converting wind to energy | Scrapbooking, animal hybridization, Academy Awards voting |

| Issues | Nuclear safety | Cruise ship safety, identity theft, social networking and privacy |

Speeches about objects convey information about any nonhuman material things. Mechanical objects, animals, plants, and fictional objects are all suitable topics of investigation. Given that this is such a broad category, strive to pick an object that your audience may not be familiar with or highlight novel relevant and interesting facts about a familiar object.

Speeches about people focus on real or fictional individuals who are living or dead. These speeches require in-depth biographical research; an encyclopedia entry is not sufficient. Introduce a new person to the audience or share little-known or surprising information about a person we already know. Although we may already be familiar with the accomplishments of historical figures and leaders, audiences often enjoy learning the “personal side” of their lives.

Speeches about concepts are less concrete than speeches about objects or people, as they focus on ideas or notions that may be abstract or multifaceted. A concept can be familiar to us, like equality, or could literally be a foreign concept like qi (or chi), which is the Chinese conception of the energy that flows through our bodies. Use the strategies discussed in this book for making content relevant and proxemic to your audience to help make abstract concepts more concrete.

Speeches about events focus on past occasions or ongoing occurrences. A particular day in history, an annual observation, or a seldom occurring event can each serve as interesting informative topics. As with speeches about people, it’s important to provide a backstory for the event, but avoid rehashing commonly known information.

Informative speeches about processes provide a step-by-step account of a procedure or natural occurrence. Speakers may walk an audience through, or demonstrate, a series of actions that take place to complete a procedure, such as making homemade cheese. Speakers can also present information about naturally occurring processes like cell division or fermentation.

Last, informative speeches about issues provide objective and balanced information about a disputed subject or a matter of concern for society. It is important that speakers view themselves as objective reporters rather than commentators to avoid tipping the balance of the speech from informative to persuasive. Rather than advocating for a particular position, the speaker should seek to teach or raise the awareness of the audience.

Researching an Informative Speech Topic

Having sharp research skills is a fundamental part of being a good informative speaker. Since informative speaking is supposed to convey factual information, speakers should take care to find sources that are objective, balanced, and credible. Periodicals, books, newspapers, and credible websites can all be useful sources for informative speeches, and you can use the guidelines for evaluating supporting materials discussed in Chapter 9 to determine the best information to include in your speech. Aside from finding credible and objective sources, informative speakers also need to take time to find engaging information. This is where sharp research skills are needed to cut through all the typical information that comes up in the research process to find novel information. Novel information is atypical or unexpected, but it takes more skill and effort to locate. Even seemingly boring informative speech topics like the history of coupons can be brought to life with information that defies the audience’s expectations. A student recently delivered an engaging speech about coupons by informing us that coupons have been around for 125 years, are most frequently used by wealthier and more educated households, and that a coupon fraud committed by an Italian American businessman named Charles Ponzi was the basis for the term Ponzi scheme, which is still commonly used today.

As a teacher, I can attest to the challenges of keeping an audience engaged during an informative presentation. While it’s frustrating to look out at my audience of students and see glazed-over eyes peering back at me, I also know that it is my responsibility to choose interesting information and convey it in a way that’s engaging. Even though the core content of what I teach hasn’t change dramatically over the years, I constantly challenge myself to bring that core information to life through application and example. As we learned earlier, finding proxemic and relevant information and examples is typically a good way to be engaging. The basic information may not change quickly, but the way people use it and the way it relates to our lives changes. Finding current, relevant examples and finding novel information are both difficult, since you, as the researcher, probably don’t know this information exists.

Here is where good research skills become necessary to be a good informative speaker. Using advice from Chapter 9 should help you begin to navigate through the seas of information to find hidden treasure that excites you and will in turn excite your audience.

As was mentioned earlier, the goal for informative speaking is to teach your audience. An audience is much more likely to remain engaged when they are actively learning. This is like a balancing act. You want your audience to be challenged enough by the information you are presenting to be interested, but not so challenged that they become overwhelmed and shut down. You should take care to consider how much information your audience already knows about a topic. Be aware that speakers who are very familiar with their speech topic tend to overestimate their audience’s knowledge about the topic. It’s better to engage your topic at a level slightly below your audience’s knowledge level than above. Most people won’t be bored by a brief review, but many people become lost and give up listening if they can’t connect to the information right away or feel it’s over their heads.

A good informative speech leaves the audience thinking long after the speech is done. Try to include some practical “takeaways” in your speech. I’ve learned many interesting and useful things from the informative speeches my students have done. Some of the takeaways are more like trivia information that is interesting to share—for example, how prohibition led to the creation of NASCAR. Other takeaways are more practical and useful—for example, how to get wine stains out of clothing and carpet or explanations of various types of student financial aid.

Organizing and Supporting an Informative Speech

You can already see that informing isn’t as easy as we may initially think. To effectively teach, a speaker must present quality information in an organized and accessible way. Once you have chosen an informative speech topic and put your research skills to the test in order to locate novel and engaging information, it’s time to organize and support your speech.

Organizational Patterns

Three organizational patterns that are particularly useful for informative speaking are topical, chronological, and spatial. As you’ll recall, to organize a speech topically, you break a larger topic down into logical subdivisions. An informative speech about labor unions could focus on unions in three different areas of employment, three historically significant strikes, or three significant legal/legislative decisions. Speeches organized chronologically trace the development of a topic or overview the steps in a process. An informative speech could trace the rise of the economic crisis in Greece or explain the steps in creating a home compost pile. Speeches organized spatially convey the layout or physical characteristics of a location or concept. An informative speech about the layout of a fire station or an astrology wheel would follow a spatial organization pattern.

Methods of Informing

Types of and strategies for incorporating supporting material into speeches are discussed in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech”, but there are some specific ways to go about developing ideas within informative speeches. Speakers often inform an audience using definitions, descriptions, demonstrations, and explanations. It is likely that a speaker will combine these methods of informing within one speech, but a speech can also be primarily organized using one of these methods.

Informing through Definition

Informing through definition entails defining concepts clearly and concisely and is an important skill for informative speaking. There are several ways a speaker can inform through definition: synonyms and antonyms, use or function, example, and etymology. Rudolph Verderber, Essentials of Informative Speaking: Theory and Contexts (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1991), 53–55. Defining a concept using a synonym or an antonym is a short and effective way to convey meaning. Synonyms are words that have the same or similar meanings, and antonyms are words that have opposite meanings. In a speech about how to effectively inform an audience, I would claim that using concrete words helps keep an audience engaged. I could enhance your understanding of what concrete means by defining it with synonyms like tangible and relatable. Or I could define concrete using antonyms like abstract and theoretical.

Identifying the use or function of an object, item, or idea is also a short way of defining. We may think we already know the use and function of most of the things we interact with regularly. This is true in obvious cases like cars, elevators, and smartphones. But there are many objects and ideas that we may rely on and interact with but not know the use or function. For example, QR codes (or quick response codes) are popping up in magazines, at airports, and even on t-shirts. Andy Vuong, “Wanna Read That QR Code? Get the Smartphone App,” The Denver Post, April 18, 2011, accessed March 6, 2012, http://www.denverpost.com/business/ci_17868932. Many people may notice them but not know what they do. As a speaker, you could define QR codes by their function by informing the audience that QR codes allow businesses, organizations, and individuals to get information to consumers/receivers through a barcode-like format that can be easily scanned by most smartphones.

A speaker can also define a topic using examples, which are cited cases that are representative of a larger concept. In an informative speech about anachronisms in movies and literature, a speaker might provide the following examples: the film Titanic shows people on lifeboats using flashlights to look for survivors from the sunken ship (such flashlights weren’t invented until two years later);The Past in Pictures, “Teaching Using Movies: Anachronisms!” accessed March 6, 2012,http://www.thepastinthepictures.wildelearning.co.uk/Introductoryunit!.htm. Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar includes a reference to a clock, even though no mechanical clocks existed during Caesar’s time. Scholasticus K, “Anachronism Examples in Literature,” February 2, 2012, accessed March 6, 2012, http://www.buzzle.com/articles/anachronism-examples-in-literature.html. Examples are a good way to repackage information that’s already been presented to help an audience retain and understand the content of a speech. Later we’ll learn more about how repackaging information enhances informative speaking.

Etymology refers to the history of a word. Defining by etymology entails providing an overview of how a word came to its current meaning. The Oxford English Dictionary is the best source for finding etymology and often contains interesting facts that can be presented as novel information to better engage your audience. For example, the word assassin, which refers to a person who intentionally murders another, literally means “hashish-eater” and comes from the Arabic word hashshashin. The current meaning emerged during the Crusades as a result of the practices of a sect of Muslims who would get high on hashish before killing Christian leaders—in essence, assassinating them. Oxford English Dictionary Online, accessed March 6, 2012, http://www.oed.com.

Informing through Description

As the saying goes, “Pictures are worth a thousand words.” Informing through description entails creating verbal pictures for your audience. Description is also an important part of informative speeches that use a spatial organizational pattern, since you need to convey the layout of a space or concept. Good descriptions are based on good observations, as they convey what is taken in through the senses and answer these type of questions: What did that look like? Smell like? Sound like? Feel like? Taste like? If descriptions are vivid and well written, they can actually invoke a sensory reaction in your audience. Just as your mouth probably begins to salivate when I suggest that you imagine biting into a fresh, bright yellow, freshly cut, juicy lemon wedge, so can your audience be transported to a setting or situation through your descriptions. I once had a student set up his speech about the history of streaking by using the following description: “Imagine that you are walking across campus to your evening class. You look up to see a parade of hundreds upon hundreds of your naked peers jogging by wearing little more than shoes.”

Informing through Demonstration

When informing through demonstration, a speaker gives verbal directions about how to do something while also physically demonstrating the steps. Early morning infomercials are good examples of demonstrative speaking, even though they are also trying to persuade us to buy their “miracle product.” Whether straightforward or complex, it’s crucial that a speaker be familiar with the content of their speech and the physical steps necessary for the demonstration. Speaking while completing a task requires advanced psycho-motor skills that most people can’t wing and therefore need to practice. Tasks suddenly become much more difficult than we expect when we have an audience. Have you ever had to type while people are reading along with you? Even though we type all the time, even one extra set of eyes seems to make our fingers more clumsy than usual.

Television chefs are excellent examples of speakers who frequently inform through demonstration. While many of them make the process of speaking while cooking look effortless, it took much practice over many years to make viewers think it is effortless.

Part of this practice also involves meeting time limits. Since television segments are limited and chefs may be demonstrating and speaking live, they have to be able to adapt as needed. Demonstration speeches are notorious for going over time, especially if speakers haven’t practiced with their visual aids / props. Be prepared to condense or edit as needed to meet your time limit. The reality competition show The Next Food Network Star (https://www.foodnetwork.com/shows/food-network-star) captures these difficulties, as many experienced cooks who have the content knowledge and know how to physically complete their tasks fall apart when faced with a camera challenge because they just assumed they could speak and cook at the same time.

Tips for Demonstration Speeches

- Include personal stories and connections to the topic, in addition to the “how-to” information, to help engage your audience.

- Ask for audience volunteers (if appropriate) to make the demonstration more interactive.

- Include a question-and-answer period at the end (if possible) so audience members can ask questions and seek clarification.

- Follow an orderly progression. Do not skip around or backtrack when reviewing the steps.

- Use clear signposts like first, second, and third.

- Use orienting material like internal previews and reviews, and transitions.

- Group steps together in categories, if needed, to help make the information more digestible.

- Assess the nonverbal feedback of your audience. Review or slow down if audience members look lost or confused.

- Practice with your visual aids / props many times. Things suddenly become more difficult and complicated than you expect when an audience is present.

- Practice for time and have contingency plans if you need to edit some information out to avoid going over your time limit.

Informing through Explanation

Informing through explanation entails sharing how something works, how something came to be, or why something happened. This method of informing may be useful when a topic is too complex or abstract to demonstrate. When presenting complex information make sure to break the topic up into manageable units, avoid information overload, and include examples that make the content relevant to the audience. Informing through explanation works well with speeches about processes, events, and issues. For example, a speaker could explain the context surrounding the Lincoln-Douglas debates or the process that takes place during presidential primaries.

“Getting Plugged In”

TED Talks as a Model of Effective Informative Speaking

Over the past few years, I have heard more and more public speaking teachers mention their use of TED speeches in their classes. What started in 1984 as a conference to gather people involved in Technology, Entertainment, and Design has now turned into a worldwide phenomenon that is known for its excellent speeches and presentations, many of which are informative in nature. “About TED,” accessed October 23, 2012, http://www.ted.com/pages/about. The motto of TED is “Ideas worth spreading,” which is in keeping with the role that we should occupy as informative speakers. We should choose topics that are worth speaking about and then work to present them in such a way that audience members leave with “take-away” information that is informative and useful. TED fits in with the purpose of the “Getting Plugged In” feature in this book because it has been technology focused from the start. For example, Andrew Blum’s speech focuses on the infrastructure of the Internet, and Pranav Mistry’s speech focuses on a new technology he developed that allows for more interaction between the physical world and the world of data. Even speakers who don’t focus on technology still skillfully use technology in their presentations, as is the case with David Gallo’s speech about exotic underwater life. Here are links to all these speeches:

Andrew Blum’s speech: What Is the Internet, Really?http://www.ted.com/talks/andrew_blum_what_is_the_internet_really.html

Pranav Mistry’s speech: The Thrilling Potential of Sixth Sense Technology.http://www.ted.com/talks/pranav_mistry_the_thrilling_potential_of_sixthsense_technology.html

David Gallo’s speech: Underwater Astonishments.http://www.ted.com/talks/david_gallo_shows_underwater_astonishments.html

What can you learn from the TED model and/or TED speakers that will help you be a better informative speaker?

In what innovative and/or informative ways do the speakers reference or incorporate technology in their speeches?

Effective Informative Speaking

There are several challenges to overcome to be an effective informative speaker. They include avoiding persuasion, avoiding information overload, and engaging your audience.

Avoiding Persuasion

We should avoid thinking of informing and persuading as dichotomous, meaning that it’s either one or the other. It’s more accurate to think of informing and persuading as two poles on a continuum, as in Figure 11.1. Thomas H. Olbricht, Informative Speaking (Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, 1968), 14. Most persuasive speeches rely on some degree of informing to substantiate the reasoning. And informative speeches, although meant to secure the understanding of an audience, may influence audience members’ beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors.

Figure 11.1 Continuum of Informing and Persuading

Speakers can look to three areas to help determine if their speech is more informative or persuasive: speaker purpose, function of information, and audience perception. Rudolph Verderber, Essentials of Informative Speaking: Theory and Contexts (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1991), 5–6. First, for informative speaking, a speaker’s purpose should be to create understanding by sharing objective, factual information. Specific purpose and thesis statements help establish a speaker’s goal and purpose and can serve as useful reference points to keep a speech on track. When reviewing your specific purpose and thesis statement, look for words like should/shouldn’t, good/bad, and right/wrong, as these often indicate a persuasive slant in the speech.

Second, information should function to clarify and explain in an informative speech. Supporting materials shouldn’t function to prove a thesis or to provide reasons for an audience to accept the thesis, as they do in persuasive speeches. Although informative messages can end up influencing the thoughts or behaviors of audience members, that shouldn’t be the goal.

Third, an audience’s perception of the information and the speaker helps determine whether a speech is classified as informative or persuasive. The audience must perceive that the information being presented is not controversial or disputed, which will lead audience members to view the information as factual. The audience must also accept the speaker as a credible source of information. Being prepared, citing credible sources, and engaging the audience help establish a speaker’s credibility. Last, an audience must perceive the speaker to be trustworthy and not have a hidden agenda. Avoiding persuasion is a common challenge for informative speakers, but it is something to consider, as violating the speaking occasion may be perceived as unethical by the audience. Be aware of the overall tone of your speech by reviewing your specific purpose and thesis to make sure your speech isn’t tipping from informative to persuasive.

Words like should/shouldn’t, good/bad, and right/wrong in a specific purpose and/or thesis statement often indicate that the speaker’s purpose is tipping from informative to persuasive.

Avoiding Information Overload

Many informative speakers have a tendency to pack a ten-minute speech with as much information as possible. This can result in information overload, which is a barrier to effective listening that occurs when a speech contains more information than an audience can process. Editing can be a difficult task, but it’s an important skill to hone, because you will be editing more than you think. Whether it’s reading through an e-mail before you send it, condensing a report down to an executive summary, or figuring out how to fit a client’s message on the front page of a brochure, you will have to learn how to discern what information is best to keep and what can be thrown out. In speaking, being a discerning editor is useful because it helps avoid information overload. While a receiver may not be attracted to a brochure that’s covered in text, they could take the time to read it, and reread it, if necessary. Audience members cannot conduct their own review while listening to a speaker live. Unlike readers, audience members can’t review words over and over. Rudolph Verderber, Essentials of Informative Speaking: Theory and Contexts (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1991), 10. Therefore competent speakers, especially informative speakers who are trying to teach their audience something, should adapt their message to a listening audience. To help avoid information overload, adapt your message to make it more listenable.

Although the results vary, research shows that people only remember a portion of a message days or even hours after receiving it. Laura Janusik, “Listening Facts,” accessed March 6, 2012, http://d1025403.site.myhosting.com/files.listen.org/Facts.htm. If you spend 100 percent of your speech introducing new information, you have wasted approximately 30 percent of your time and your audience’s time. Information overload is a barrier to effective listening, and as good speakers, we should be aware of the limitations of listening and compensate for that in our speech preparation and presentation. I recommend that my students follow a guideline that suggests spending no more than 30 percent of your speech introducing new material and 70 percent of your speech repackaging that information. I specifically use the word repackaging and not repeating. Simply repeating the same information would also be a barrier to effective listening, since people would just get bored. Repackaging will help ensure that your audience retains most of the key information in the speech. Even if they don’t remember every example, they will remember the main underlying point.

Avoiding information overload requires a speaker to be a good translator of information. To be a good translator, you can compare an unfamiliar concept with something familiar, give examples from real life, connect your information to current events or popular culture, or supplement supporting material like statistics with related translations of that information. These are just some of the strategies a good speaker can use. While translating information is important for any oral presentation, it is especially important when conveying technical information. Being able to translate complex or technical information for a lay audience leads to more effective informing, because the audience feels like they are being addressed on their level and don’t feel lost or “talked down to.” The History Channel show The Universe provides excellent examples of informative speakers who act as good translators. The scientists and experts featured on the show are masters of translating technical information, like physics, into concrete examples that most people can relate to based on their everyday experiences.

Following the guidelines established in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech” for organizing a speech can also help a speaker avoid information overload. Good speakers build in repetition and redundancy to make their content more memorable and their speech more consumable. Preview statements, section transitions, and review statements are some examples of orienting material that helps focus an audience’s attention and facilitates the process of informing. Rudolph Verderber, Essentials of Informative Speaking: Theory and Contexts (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1991), 12.

Engaging Your Audience

As a speaker, you are competing for the attention of your audience against other internal and external stimuli. Getting an audience engaged and then keeping their attention is a challenge for any speaker, but it can be especially difficult when speaking to inform. As was discussed earlier, once you are in the professional world, you will most likely be speaking informatively about topics related to your experience and expertise. Some speakers fall into the trap of thinking that their content knowledge is enough to sustain them through an informative speech or that their position in an organization means that an audience will listen to them and appreciate their information despite their delivery. Content expertise is not enough to be an effective speaker. A person must also have speaking expertise. Rudolph Verderber, Essentials of Informative Speaking: Theory and Contexts (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1991), 4. Effective speakers, even renowned experts, must still translate their wealth of content knowledge into information that is suited for oral transmission, audience centered, and well organized. I’m sure we’re all familiar with the stereotype of the absentminded professor or the genius who thinks elegantly in his or her head but can’t convey that same elegance verbally. Having well-researched and organized supporting material is an important part of effective informative speaking, but having good content is not enough.

Audience members are more likely to stay engaged with a speaker they view as credible. So complementing good supporting material with a practiced and fluent delivery increases credibility and audience engagement. In addition, as we discussed earlier, good informative speakers act as translators of information. Repackaging information into concrete familiar examples is also a strategy for making your speech more engaging. Understanding relies on being able to apply incoming information to life experiences.

Repackaging information is also a good way to appeal to different learning styles, as you can present the same content in various ways, which helps reiterate a point. While this strategy is useful with any speech, since the goal of informing is teaching, it makes sense to include a focus on learning within your audience adaptation. There are three main learning styles that help determine how people most effectively receive and process information: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. Neil Fleming, “The VARK Helpsheets,” accessed March 6, 2012, http://www.vark-learn.com/english/page.asp?p=helpsheets. Visual learners respond well to information presented via visual aids, so repackage information using text, graphics, charts and other media. Public speaking is a good way to present information for auditory learners who process information well when they hear it. Kinesthetic learners are tactile; they like to learn through movement and “doing.” Asking for volunteers to help with a demonstration, if appropriate, is a way to involve kinesthetic learners in your speech. You can also have an interactive review activity at the end of a speech, much like many teachers incorporate an activity after a lesson to reinforce the material.

Sample Informative Speech

Title: Going Green in the World of Education

General purpose: To inform

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, the audience will be able to describe some ways in which schools are going green.

Thesis statement: The green movement has transformed school buildings, how teachers teach, and the environment in which students learn.

Introduction

Attention getter: Did you know that attending or working at a green school can lead students and teachers to have less health problems? Did you know that allowing more daylight into school buildings increases academic performance and can lessen attention and concentration challenges? Well, the research I will cite in my speech supports both of these claims, and these are just two of the many reasons why more schools, both grade schools and colleges, are going green.

Introduction of topic: Today, I’m going to inform you about the green movement that is affecting many schools.

Credibility and relevance: Because of my own desire to go into the field of education, I decided to research how schools are going green in the United States. But it’s not just current and/or future teachers that will be affected by this trend. As students at Eastern Illinois University, you are already asked to make “greener” choices. Whether it’s the little signs in the dorm rooms that ask you to turn off your lights when you leave the room, the reusable water bottles that were given out on move-in day, or even our new Renewable Energy Center, the list goes on and on. Additionally, younger people in our lives, whether they be future children or younger siblings or relatives, will likely be affected by this continuing trend.

Preview statement: In order to better understand what makes a “green school,” we need to learn about how K–12 schools are going green, how college campuses are going green, and how these changes affect students and teachers.

Transition: I’ll begin with how K–12 schools are going green.

Body

I. According to the “About Us” section on their official website, the US Green Building Council was established in 1993 with the mission to promote sustainability in the building and construction industry, and it is this organization that is responsible for the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, or LEED, which is a well-respected green building certification system. While homes, neighborhoods, and businesses can also pursue LEED certification, I’ll focus today on K–12 schools and college campuses.

A. It’s important to note that principles of “going green” can be applied to the planning of a building from its first inception or be retroactively applied to existing buildings.

1. A 2011 article by Ash in Education Week notes that the pathway to creating a greener school is flexible based on the community and its needs.

a. In order to garner support for green initiatives, the article recommends that local leaders like superintendents, mayors, and college administrators become involved in the green movement.

b. Once local leaders are involved, the community, students, parents, faculty, and staff can be involved by serving on a task force, hosting a summit or conference, and implementing lessons about sustainability into everyday conversations and school curriculum.

2. The US Green Building Council’s website also includes a tool kit with a lot of information about how to “green” existing schools.

B. Much of the efforts to green schools have focused on K–12 schools and districts, but what makes a school green?

1. According to the US Green Building Council’s Center for Green Schools, green school buildings conserve energy and natural resources.

a. For example, Fossil Ridge High School in Fort Collins, Colorado, was built in 2006 and received LEED certification because it has automatic light sensors to conserve electricity and uses wind energy to offset nonrenewable energy use.

b. To conserve water, the school uses a pond for irrigation, has artificial turf on athletic fields, and installed low-flow toilets and faucets.

c. According to the 2006 report by certified energy manager Gregory Kats titled “Greening America’s Schools,” a LEED certified school uses 30–50 percent less energy, 30 percent less water, and reduces carbon dioxide emissions by 40 percent compared to a conventional school.

2. The Center for Green Schools also presents case studies that show how green school buildings also create healthier learning environments.

a. Many new building materials, carpeting, and furniture contain chemicals that are released into the air, which reduces indoor air quality.

b. So green schools purposefully purchase materials that are low in these chemicals.

c. Natural light and fresh air have also been shown to promote a healthier learning environment, so green buildings allow more daylight in and include functioning windows.

Transition: As you can see, K–12 schools are becoming greener; college campuses are also starting to go green.

II. Examples from the University of Denver and Eastern Illinois University show some of the potential for greener campuses around the country.

A. The University of Denver is home to the nation’s first “green” law school.

1. According to the Sturm College of Law’s website, the building was designed to use 40 percent less energy than a conventional building through the use of movement-sensor lighting; high-performance insulation in the walls, floors, and roof; and infrared sensors on water faucets and toilets.

2. Electric car recharging stations were also included in the parking garage, and the building has extra bike racks and even showers that students and faculty can use to freshen up if they bike or walk to school or work.

B. Eastern Illinois University has also made strides toward a more green campus.

1. Some of the dining halls on campus have gone “trayless,” which according to a 2009 article by Calder in the journal Independent School has the potential to dramatically reduce the amount of water and chemical use, since there are no longer trays to wash, and also helps reduce food waste since people take less food without a tray.

2. The biggest change on campus has been the opening of the Renewable Energy Center in 2011, which according to EIU’s website is one of the largest biomass renewable energy projects in the country.

a. The Renewable Energy Center uses slow-burn technology to use wood chips that are a byproduct of the lumber industry that would normally be discarded.

b. This helps reduce our dependency on our old coal-fired power plant, which reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

c. The project was the first known power plant to be registered with the US Green Building Council and is on track to receive LEED certification.

Transition: All these efforts to go green in K–12 schools and on college campuses will obviously affect students and teachers at the schools.

III. The green movement affects students and teachers in a variety of ways.

A. Research shows that going green positively affects a student’s health.

1. Many schools are literally going green by including more green spaces such as recreation areas, gardens, and greenhouses, which according to a 2010 article in the Journal of Environmental Education by University of Colorado professor Susan Strife has been shown to benefit a child’s cognitive skills, especially in the areas of increased concentration and attention capacity.

2. Additionally, the report I cited earlier, “Greening America’s Schools,” states that the improved air quality in green schools can lead to a 38 percent reduction in asthma incidents and that students in “green schools” had 51 percent less chance of catching a cold or the flu compared to children in conventional schools.

B. Standard steps taken to green schools can also help students academically.

1. The report “Greening America’s Schools” notes that a recent synthesis of fifty-three studies found that more daylight in the school building leads to higher academic achievement.

2. The report also provides data that show how the healthier environment in green schools leads to better attendance and that in Washington, DC, and Chicago, schools improved their performance on standardized tests by 3–4 percent.

C. Going green can influence teachers’ lesson plans as well their job satisfaction and physical health.

1. There are several options for teachers who want to “green” their curriculum.

a. According to the article in Education Week that I cited earlier, the Sustainability Education Clearinghouse is a free online tool that provides K–12 educators with the ability to share sustainability-oriented lesson ideas.

b. The Center for Green Schools also provides resources for all levels of teachers, from kindergarten to college, that can be used in the classroom.

2. The report “Greening America’s Schools” claims that the overall improved working environment that a green school provides leads to higher teacher retention and less teacher turnover.

3. Just as students see health benefits from green schools, so do teachers, as the same report shows that teachers in these schools get sick less, resulting in a decrease of sick days by 7 percent.

Conclusion

Transition to conclusion and summary of importance: In summary, the going-green era has impacted every aspect of education in our school systems.

Review of main points: From K–12 schools to college campuses like ours, to the students and teachers in the schools, the green movement is changing the way we think about education and our environment.

Closing statement: As Glenn Cook, the editor in chief of the American School Board Journal, states on the Center for Green Schools’s website, “The green schools movement is the biggest thing to happen to education since the introduction of technology to the classroom.”

References

Ash, K. (2011). “Green schools” benefit budgets and students, report says. Education Week, 30(32), 10.

Calder, W. (2009). Go green, save green. Independent School, 68(4), 90–93.

The Center for Green Schools. (n.d.). K–12: How. Retrieved from http://www.centerforgreenschools.org/main-nav/k-12/buildings.aspx

Eastern Illinois University. (n.d.). Renewable Energy Center. Retrieved from http://www.eiu.edu/sustainability/eiu_renewable.php

Kats, G. (2006). Greening America’s schools: Costs and benefits. A Capital E Report. Retrieved from http://www.usgbc.org/ShowFile.aspx?DocumentID=2908

Strife, S. (2010). Reflecting on environmental education: Where is our place in the green movement? Journal of Environmental Education, 41(3), 179–191. doi:10.1080/00958960903295233

Sturm College of Law. (n.d.). About DU law: Building green. Retrieved from http://www.law.du.edu/index.php/about/building-green

USGBC. (n.d.). About us. US Green Building Council. Retrieved from https://new.usgbc.org/about

Key Takeaways

Getting integrated: Informative speaking is likely the type of public speaking we will most often deliver and be audience to in our lives. Informative speaking is an important part of academic, professional, personal, and civic contexts.

Informative speeches teach an audience through objective factual information and can emerge from one or more of the following categories: objects, people, concepts, events, processes, and issues.Effective informative speaking requires good research skills, as speakers must include novel information, relevant and proxemic examples, and “take-away” information that audience members will find engaging and useful.

The four primary methods of informing are through definition, description, demonstration, or explanation.

Informing through definition entails defining concepts clearly and concisely using synonyms and antonyms, use or function, example, or etymology.

Informing through description entails creating detailed verbal pictures for your audience.

Informing through demonstration entails sharing verbal directions about how to do something while also physically demonstrating the steps.

Informing through explanation entails sharing how something works, how something came to be, or why something happened.

An effective informative speaker should avoid persuasion by reviewing the language used in the specific purpose and thesis statements, using objective supporting material, and appearing trustworthy to the audience.

An effective informative speaker should avoid information overload by repackaging information and building in repetition and orienting material like reviews and previews.

An effective informative speaker engages the audience by translating information into relevant and concrete examples that appeal to different learning styles.

Exercises

Getting integrated: How might you use informative speaking in each of the following contexts: academic, professional, personal, and civic?

Brainstorm potential topics for your informative speech and identify which topic category each idea falls into. Are there any risks of persuading for the topics you listed? If so, how can you avoid persuasion if you choose that topic?

Of the four methods of informing (through definition, description, demonstration, or explanation), which do you think is most effective for you? Why?

11.2 Persuasive Speaking

Learning Objectives

Explain how claims, evidence, and warrants function to create an argument.

Identify strategies for choosing a persuasive speech topic.

Identify strategies for adapting a persuasive speech based on an audience’s orientation to the proposition.

Distinguish among propositions of fact, value, and policy.

Choose an organizational pattern that is fitting for a persuasive speech topic.

We produce and receive persuasive messages daily, but we don’t often stop to think about how we make the arguments we do or the quality of the arguments that we receive. In this section, we’ll learn the components of an argument, how to choose a good persuasive speech topic, and how to adapt and organize a persuasive message.

Foundation of Persuasion

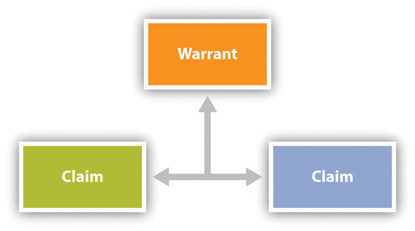

Persuasive speaking seeks to influence the beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors of audience members. In order to persuade, a speaker has to construct arguments that appeal to audience members. Arguments form around three components: claim, evidence, and warrant. The claim is the statement that will be supported by evidence. Your thesis statement is the overarching claim for your speech, but you will make other claims within the speech to support the larger thesis. Evidence, also called grounds, supports the claim. The main points of your persuasive speech and the supporting material you include serve as evidence. For example, a speaker may make the following claim: “There should be a national law against texting while driving.” The speaker could then support the claim by providing the following evidence: “Research from the US Department of Transportation has found that texting while driving creates a crash risk that is twenty-three times worse than driving while not distracted.” The warrant is the underlying justification that connects the claim and the evidence. One warrant for the claim and evidence cited in this example is that the US Department of Transportation is an institution that funds research conducted by credible experts. An additional and more implicit warrant is that people shouldn’t do things they know are unsafe.

Figure 11.2 Components of an Argument [Note: This graphic is incorrect. The lower left box should read “Evidence”, not “Claim”.]

The quality of your evidence often impacts the strength of your warrant, and some warrants are stronger than others. A speaker could also provide evidence to support their claim advocating for a national ban on texting and driving by saying, “I have personally seen people almost wreck while trying to text.” While this type of evidence can also be persuasive, it provides a different type and strength of warrant since it is based on personal experience. In general, the anecdotal evidence from personal experience would be given a weaker warrant than the evidence from the national research report. The same process works in our legal system when a judge evaluates the connection between a claim and evidence. If someone steals my car, I could say to the police, “I’m pretty sure Mario did it because when I said hi to him on campus the other day, he didn’t say hi back, which proves he’s mad at me.” A judge faced with that evidence is unlikely to issue a warrant for Mario’s arrest. Fingerprint evidence from the steering wheel that has been matched with a suspect is much more likely to warrant arrest.

As you put together a persuasive argument, you act as the judge. You can evaluate arguments that you come across in your research by analyzing the connection (the warrant) between the claim and the evidence. If the warrant is strong, you may want to highlight that argument in your speech. You may also be able to point out a weak warrant in an argument that goes against your position, which you could then include in your speech. Every argument starts by putting together a claim and evidence, but arguments grow to include many interrelated units.

Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

As with any speech, topic selection is important and is influenced by many factors. Good persuasive speech topics are current, controversial, and have important implications for society. If your topic is currently being discussed on television, in newspapers, in the lounges in your dorm, or around your family’s dinner table, then it’s a current topic. A persuasive speech aimed at getting audience members to wear seat belts in cars wouldn’t have much current relevance, given that statistics consistently show that most people wear seat belts. Giving the same speech would have been much more timely in the 1970s when there was a huge movement to increase seat-belt use.

Many topics that are current are also controversial, which is what gets them attention by the media and citizens. Current and controversial topics will be more engaging for your audience. A persuasive speech to encourage audience members to donate blood or recycle wouldn’t be very controversial, since the benefits of both practices are widely agreed on. However, arguing that the restrictions on blood donation by men who have had sexual relations with men be lifted would be controversial. I must caution here that controversial is not the same as inflammatory. An inflammatory topic is one that evokes strong reactions from an audience for the sake of provoking a reaction. Being provocative for no good reason or choosing a topic that is extremist will damage your credibility and prevent you from achieving your speech goals.

You should also choose a topic that is important to you and to society as a whole. As we have already discussed in this book, our voices are powerful, as it is through communication that we participate and make change in society. Therefore we should take seriously opportunities to use our voices to speak publicly. Choosing a speech topic that has implications for society is probably a better application of your public speaking skills than choosing to persuade the audience that Lebron James is the best basketball player in the world or that Superman is a better hero than Spiderman. Although those topics may be very important to you, they don’t carry the same social weight as many other topics you could choose to discuss. Remember that speakers have ethical obligations to the audience and should take the opportunity to speak seriously.

You will also want to choose a topic that connects to your own interests and passions. If you are an education major, it might make more sense to do a persuasive speech about funding for public education than the death penalty. If there are hot-button issues for you that make you get fired up and veins bulge out in your neck, then it may be a good idea to avoid those when speaking in an academic or professional context.

Choosing such topics may interfere with your ability to deliver a speech in a competent and ethical manner. You want to care about your topic, but you also want to be able to approach it in a way that’s going to make people want to listen to you. Most people tune out speakers they perceive to be too ideologically entrenched and write them off as extremists or zealots.

You also want to ensure that your topic is actually persuasive. Draft your thesis statement as an “I believe” statement so your stance on an issue is clear. Also, think of your main points as reasons to support your thesis. Students end up with speeches that aren’t very persuasive in nature if they don’t think of their main points as reasons. Identifying arguments that counter your thesis is also a good exercise to help ensure your topic is persuasive. If you can clearly and easily identify a competing thesis statement and supporting reasons, then your topic and approach are arguable.

Review of Tips for Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

Choose a topic that is current.

Not current. People should use seat belts.

Current. People should not text while driving.

Choose a topic that is controversial.

Not controversial. People should recycle.

Controversial. Recycling should be mandatory by law.

Choose a topic that meaningfully impacts society.

Not as impactful. Superman is the best superhero.

Impactful. Colleges and universities should adopt zero-tolerance bullying policies.

Write a thesis statement that is clearly argumentative and states your stance.

Unclear thesis. Homeschooling is common in the United States.

Clear, argumentative thesis with stance. Homeschooling does not provide the same benefits of traditional education and should be strictly monitored and limited.

Adapting Persuasive Messages

Competent speakers should consider their audience throughout the speech-making process. Given that persuasive messages seek to directly influence the audience in some way, audience adaptation becomes even more important. If possible, poll your audience to find out their orientation toward your thesis. I read my students’ thesis statements aloud and have the class indicate whether they agree with, disagree with, or are neutral in regards to the proposition. It is unlikely that you will have a homogenous audience, meaning that there will probably be some who agree, some who disagree, and some who are neutral. So you may employ all of the following strategies, in varying degrees, in your persuasive speech.

When you have audience members who already agree with your proposition, you should focus on intensifying their agreement. You can also assume that they have foundational background knowledge of the topic, which means you can take the time to inform them about lesser-known aspects of a topic or cause to further reinforce their agreement. Rather than move these audience members from disagreement to agreement, you can focus on moving them from agreement to action. Remember, calls to action should be as specific as possible to help you capitalize on audience members’ motivation in the moment so they are more likely to follow through on the action.

There are two main reasons audience members may be neutral in regards to your topic: (1) they are uninformed about the topic or (2) they do not think the topic affects them. In this case, you should focus on instilling a concern for the topic. Uninformed audiences may need background information before they can decide if they agree or disagree with your proposition. If the issue is familiar but audience members are neutral because they don’t see how the topic affects them, focus on getting the audience’s attention and demonstrating relevance. Remember that concrete and proxemic supporting materials will help an audience find relevance in a topic. Students who pick narrow or unfamiliar topics will have to work harder to persuade their audience, but neutral audiences often provide the most chance of achieving your speech goal since even a small change may move them into agreement.

When audience members disagree with your proposition, you should focus on changing their minds. To effectively persuade, you must be seen as a credible speaker. When an audience is hostile to your proposition, establishing credibility is even more important, as audience members may be quick to discount or discredit someone who doesn’t appear prepared or doesn’t present well-researched and supported information. Don’t give an audience a chance to write you off before you even get to share your best evidence. When facing a disagreeable audience, the goal should also be small change. You may not be able to switch someone’s position completely, but influencing him or her is still a success. Aside from establishing your credibility, you should also establish common ground with an audience.

Acknowledging areas of disagreement and logically refuting counterarguments in your speech is also a way to approach persuading an audience in disagreement, as it shows that you are open-minded enough to engage with other perspectives.

Determining Your Proposition

The proposition of your speech is the overall direction of the content and how that relates to the speech goal. A persuasive speech will fall primarily into one of three categories: propositions of fact, value, or policy. A speech may have elements of any of the three propositions, but you can usually determine the overall proposition of a speech from the specific purpose and thesis statements.

Propositions of fact focus on beliefs and try to establish that something “is or isn’t.” Propositions of value focus on persuading audience members that something is “good or bad,” “right or wrong,” or “desirable or undesirable.” Propositions of policy advocate that something “should or shouldn’t” be done. Since most persuasive speech topics can be approached as propositions of fact, value, or policy, it is a good idea to start thinking about what kind of proposition you want to make, as it will influence how you go about your research and writing. As you can see in the following example using the topic of global warming, the type of proposition changes the types of supporting materials you would need:

- Proposition of fact. Global warming is caused by increased greenhouse gases related to human activity.

- Proposition of value. America’s disproportionately large amount of pollution relative to other countries is wrong.

- Proposition of policy. There should be stricter emission restrictions on individual cars.

To support propositions of fact, you would want to present a logical argument based on objective facts that can then be used to build persuasive arguments. Propositions of value may require you to appeal more to your audience’s emotions and cite expert and lay testimony. Persuasive speeches about policy usually require you to research existing and previous laws or procedures and determine if any relevant legislation or propositions are currently being considered.

“Getting Critical”

Persuasion and Masculinity

The traditional view of rhetoric that started in ancient Greece and still informs much of our views on persuasion today has been critiqued for containing Western and masculine biases. Traditional persuasion has been linked to Western and masculine values of domination, competition, and change, which have been critiqued as coercive and violent. Sally M. Gearhart, “The Womanization of Rhetoric,” Women’s Studies International Quarterly 2 (1979): 195–201.

Communication scholars proposed an alternative to traditional persuasive rhetoric in the form of invitational rhetoric. Invitational rhetoric differs from a traditional view of persuasive rhetoric that “attempts to win over an opponent, or to advocate the correctness of a single position in a very complex issue.” Jennifer Emerling Bone, Cindy L. Griffin, and T. M. Linda Scholz, “Beyond Traditional Conceptualizations of Rhetoric: Invitational Rhetoric and a Move toward Civility,” Western Journal of Communication 72 (2008): 436. Instead, invitational rhetoric proposes a model of reaching consensus through dialogue. The goal is to create a climate in which growth and change can occur but isn’t required for one person to “win” an argument over another. Each person in a communication situation is acknowledged to have a standpoint that is valid but can still be influenced through the offering of alternative perspectives and the invitation to engage with and discuss these standpoints. Kathleen J. Ryan and Elizabeth J. Natalle, “Fusing Horizons: Standpoint Hermeneutics and Invitational Rhetoric,” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 31 (2001): 69–90. Safety, value, and freedom are three important parts of invitational rhetoric. Safety involves a feeling of security in which audience members and speakers feel like their ideas and contributions will not be denigrated. Value refers to the notion that each person in a communication encounter is worthy of recognition and that people are willing to step outside their own perspectives to better understand others. Last, freedom is present in communication when communicators do not limit the thinking or decisions of others, allowing all participants to speak up. Jennifer Emerling Bone, Cindy L. Griffin, and T. M. Linda Scholz, “Beyond Traditional Conceptualizations of Rhetoric: Invitational Rhetoric and a Move toward Civility,” Western Journal of Communication 72 (2008): 436–37.

Invitational rhetoric doesn’t claim that all persuasive rhetoric is violent. Instead, it acknowledges that some persuasion is violent and that the connection between persuasion and violence is worth exploring. Invitational rhetoric has the potential to contribute to the civility of communication in our society. When we are civil, we are capable of engaging with and appreciating different perspectives while still understanding our own. People aren’t attacked or reviled because their views diverge from ours. Rather than reducing the world to “us against them, black or white, and right or wrong,” invitational rhetoric encourages us to acknowledge human perspectives in all their complexity. Jennifer Emerling Bone, Cindy L. Griffin, and T. M. Linda Scholz, “Beyond Traditional Conceptualizations of Rhetoric: Invitational Rhetoric and a Move toward Civility,” Western Journal of Communication 72 (2008): 457.

What is your reaction to the claim that persuasion includes Western and masculine biases?

What are some strengths and weaknesses of the proposed alternatives to traditional persuasion?

In what situations might an invitational approach to persuasion be useful? In what situations might you want to rely on traditional models of persuasion?

Organizing a Persuasive Speech

We have already discussed several patterns for organizing your speech, but some organization strategies are specific to persuasive speaking. Some persuasive speech topics lend themselves to a topical organization pattern, which breaks the larger topic up into logical divisions. Earlier, in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech”, we discussed recency and primacy, and in this chapter we discussed adapting a persuasive speech based on the audience’s orientation toward the proposition. These concepts can be connected when organizing a persuasive speech topically. Primacy means putting your strongest information first and is based on the idea that audience members put more weight on what they hear first. This strategy can be especially useful when addressing an audience that disagrees with your proposition, as you can try to win them over early. Recency means putting your strongest information last to leave a powerful impression. This can be useful when you are building to a climax in your speech, specifically if you include a call to action.

The problem-solution pattern is an organizational pattern that advocates for a particular approach to solve a problem. You would provide evidence to show that a problem exists and then propose a solution with additional evidence or reasoning to justify the course of action. One main point addressing the problem and one main point addressing the solution may be sufficient, but you are not limited to two. You could add a main point between the problem and solution that outlines other solutions that have failed. You can also combine the problem-solution pattern with the cause-effect pattern or expand the speech to fit with Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

As was mentioned in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech”, the cause-effect pattern can be used for informative speaking when the relationship between the cause and effect is not contested. The pattern is more fitting for persuasive speeches when the relationship between the cause and effect is controversial or unclear. There are several ways to use causes and effects to structure a speech. You could have a two-point speech that argues from cause to effect or from effect to cause. You could also have more than one cause that lead to the same effect or a single cause that leads to multiple effects. The following are some examples of thesis statements that correspond to various organizational patterns. As you can see, the same general topic area, prison overcrowding, is used for each example. This illustrates the importance of considering your organizational options early in the speech-making process, since the pattern you choose will influence your researching and writing.

Persuasive Speech Thesis Statements by Organizational Pattern

- Problem-solution. Prison overcrowding is a serious problem that we can solve by finding alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

- Problem–failed solution–proposed solution. Prison overcrowding is a serious problem that shouldn’t be solved by building more prisons; instead, we should support alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

- Cause-effect. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-cause-effect. State budgets are being slashed and prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-effect-effect. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to increased behavioral problems among inmates and lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-effect-solution. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals; therefore we need to find alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence is an organizational pattern designed for persuasive speaking that appeals to audience members’ needs and motivates them to action. If your persuasive speaking goals include a call to action, you may want to consider this organizational pattern. We already learned about the five steps of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech”, but we will review them here with an example:

Step 1: Attention

- Hook the audience by making the topic relevant to them.

- Imagine living a full life, retiring, and slipping into your golden years. As you get older you become more dependent on others and move into an assisted-living facility. Although you think life will be easier, things get worse as you experience abuse and mistreatment from the staff. You report the abuse to a nurse and wait, but nothing happens and the abuse continues. Elder abuse is a common occurrence, and unlike child abuse, there are no laws in our state that mandate complaints of elder abuse be reported or investigated.

Step 2: Need

- Cite evidence to support the fact that the issue needs to be addressed.

- According to the American Psychological Association, one to two million elderly US Americans have been abused by their caretakers. In our state, those in the medical, psychiatric, and social work field are required to report suspicion of child abuse but are not mandated to report suspicions of elder abuse.

Step 3: Satisfaction

- Offer a solution and persuade the audience that it is feasible and well thought out.

- There should be a federal law mandating that suspicion of elder abuse be reported and that all claims of elder abuse be investigated.

Step 4: Visualization

- Take the audience beyond your solution and help them visualize the positive results of implementing it or the negative consequences of not.

- Elderly people should not have to live in fear during their golden years. A mandatory reporting law for elderly abuse will help ensure that the voices of our elderly loved ones will be heard.

Step 5: Action

- Call your audience to action by giving them concrete steps to follow to engage in a particular action or to change a thought or behavior.

- I urge you to take action in two ways. First, raise awareness about this issue by talking to your own friends and family. Second, contact your representatives at the state and national level to let them know that elder abuse should be taken seriously and given the same level of importance as other forms of abuse. I brought cards with the contact information for our state and national representatives for this area. Please take one at the end of my speech. A short e-mail or phone call can help end the silence surrounding elder abuse.

Key Takeaways

Good persuasive speech topics are current, controversial (but not inflammatory), and important to the speaker and society.

When audience members agree with the proposal, focus on intensifying their agreement and moving them to action.

When audience members disagree with the proposal, focus on establishing your credibility, build common ground with the audience, and incorporate counterarguments and refute them.

Propositions of fact focus on establishing that something “is or isn’t” or is “true or false.”

Propositions of policy advocate that something “should or shouldn’t” be done.

Persuasive speeches can be organized using the following patterns: problem-solution, cause-effect, cause-effect-solution, or Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

Exercises

Getting integrated: Give an example of persuasive messages that you might need to create in each of the following contexts: academic, professional, personal, and civic. Then do the same thing for persuasive messages you may receive.

To help ensure that your persuasive speech topic is persuasive and not informative, identify the claims, evidence, and warrants you may use in your argument. In addition, write a thesis statement that refutes your topic idea and identify evidence and warrants that could support that counterargument.

Determine if your speech is primarily a proposition of fact, value, or policy. How can you tell? Identify an organizational pattern that you think will work well for your speech topic, draft one sentence for each of your main points, and arrange them according to the pattern you chose.

11.3 Persuasive Reasoning and Fallacies

Learning Objectives

Define inductive, deductive, and causal reasoning.

Evaluate the quality of inductive, deductive, and causal reasoning.

Identify common fallacies of reasoning.

Persuasive speakers should be concerned with what strengthens and weakens an argument. Earlier we discussed the process of building an argument with claims and evidence and how warrants are the underlying justifications that connect the two. We also discussed the importance of evaluating the strength of a warrant, because strong warrants are usually more persuasive. Knowing different types of reasoning can help you put claims and evidence together in persuasive ways and help you evaluate the quality of arguments that you encounter. Further, being able to identify common fallacies of reasoning can help you be a more critical consumer of persuasive messages.

Reasoning

Reasoning refers to the process of making sense of things around us. In order to understand our experiences, draw conclusions from information, and present new ideas, we must use reasoning. We often reason without being aware of it, but becoming more aware of how we think can empower us to be better producers and consumers of communicative messages. The three types of reasoning we will explore are inductive, deductive, and causal.

Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning reaches conclusions through the citation of examples and is the most frequently used form of logical reasoning. Otis M. Walter, Speaking to Inform and Persuade (New York: Macmillan, 1966), 58. While introductory speakers are initially attracted to inductive reasoning because it seems easy, it can be difficult to employ well. Inductive reasoning, unlike deductive reasoning, doesn’t result in true or false conclusions. Instead, since conclusions are generalized based on observations or examples, conclusions are “more likely” or “less likely.” Despite the fact that this type of reasoning isn’t definitive, it can still be valid and persuasive.

Some arguments based on inductive reasoning will be more cogent, or convincing and relevant, than others. For example, inductive reasoning can be weak when claims are made too generally. An argument that fraternities should be abolished from campus because they contribute to underage drinking and do not uphold high academic standards could be countered by providing examples of fraternities that sponsor alcohol education programming for the campus and have members that have excelled academically. Otis M. Walter, Speaking to Inform and Persuade (New York: Macmillan, 1966), 58. In this case, one overly general claim is countered by another general claim, and both of them have some merit. It would be more effective to present a series of facts and reasons and then share the conclusion or generalization that you have reached from them.