Chapter 16 – New Media and Communication

Media and communication work together in powerful ways. New technologies develop and diffuse into regular usage by large numbers of people, which in turn shapes how we communicate and how we view our society and ourselves. The transition over the past twenty or so years from “old media” to “new media” marks a significant change in how we use technology to communicate, as devices and the messages carried on them move from “mass” to “micro” and our relationship with new media becomes much more personal and social than it was with old media. This chapter is just an introduction to the dynamic area of research and development involving new media and communication.

16.1 New Media Technologies

Learning Objectives

Trace the evolution of new media.

Discuss how new media are more personal and social than old media.

So what makes “new media” new media? When we consider “old media,” which consist of mainly print, radio, and television/movies, we see that their presence in our lives and our societies was limited to a few places. For example, television and radio have long been key technology features in the home. Movies were primarily enjoyed in theaters until VCRs and DVD players brought them into our homes. The closest thing to a portable mass medium was reading a book or paper on a commute to and from work. New media, however, are more personal and more social than old media, which creates a paradox we will explore later in this chapter, as we discuss how new media simultaneously separate and connect us. In this section, we will trace the evolution of new media and discuss how personal media and social media fit under the umbrella of new media.

The Evolution of New Media

New media, as we are discussing them here, couldn’t exist without the move from analogue to digital technology, as all the types of new media we will discuss are digitally based. Eugenia Siapera, Understanding New Media (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2012), 3. Digital media are composed of and/or are designed to read numerical codes (hence the root word digit). The most commonly used system of numbers is binary code, which converts information into a series of 0s and 1s. This shared code system means that any machine that can decode (read) binary code can make sense of, store, and replay the information. Analogue media are created by encoding information onto a physical object that must then be paired with another device capable of reading that specific code. So what most distinguishes analogue media from digital media are their physicality and their need to be matched with a specific decoding device. In terms of physicality, analogue media are a combination of mechanical and physical parts, while digital media can be completely electronic and have no physicality; think of an MP3 music file, for example. To understand the second distinction between analogue and digital media, we can look at predigital music and how various types of analogue music had to be paired with a specific decoding device. To make recordings using old media technology, grooves were carved into vinyl to make records or changes were made in the electromagnetic signature of ribbon or tape to make cassette tapes. So each of these physical objects must be paired with a specific device, such as a record player or a cassette deck, to be able to decode and listen to the music. New media changed how we collect and listen to music. Many people who came of age in the digital revolution are now so used to having digital music that the notion of a physical music collection is completely foreign to them. Now music files are stored electronically and can be played on many different platforms, including iPods, computers, and smartphones.

In news coverage and academic scholarship, you will see several different terms used when discussing new media. Other terms used include digital media, online media, social media, and personal media. For the sake of our discussion, we will subsume all these under the term new media. The term new media itself has been critiqued by some for setting up a false dichotomy between new and old. The technology that made new media possible has been in development for many years. The Internet has existed in some capacity for more than forty years, and the World Wide Web, which made the Internet accessible to the masses, just celebrated its twenty-first birthday in August of 2012.

So in addition to the word new helping us realize some key technological changes from older forms of media, we should also think of new as present and future oriented, since media and technology are now changing faster than ever before. In short, what is new today may not be considered new in a week. Despite the rapid changes in technology, the multiplatform compatibility of much of new media paradoxically allows for some stability. Whereas new technology often made analogue media devices and products obsolete, the format of much of the new media objects stays the same even as newer and updated devices with which to access digital media become available. Key to new media is the notion of technological convergence. Most new media are already digital, and the ongoing digitalization of old media allows them to circulate freely and be read/accessed/played by any digital media platform without the need for conversion. Eugenia Siapera, Understanding New Media (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2012), 47. This multiplatform compatibility has never existed before, as each type of media had a corresponding platform. For example, you couldn’t play records in an eight-track cassette tape player or a VHS tape in a DVD player. Likewise, whereas machines that printed words on paper and the human eye were the encoding and decoding devices needed to engage with analogue forms of print media, you can read this textbook in print, on a computer, or on an e-reader, iPad, smartphone, or other handheld device. Another characteristic of new media is the blurring of lines between producers and consumers, as individual users now have a more personal relationship with their media.

Personal Media

Personal media is so named because users are more free to choose the media content to which they want to be exposed, to generate their own content, to comment on and link to other content, to share content with others, and, in general, to create personalized media environments. To better understand personal media, we must take a look at personal media devices and the messages and social connections they facilitate.

In terms of devices, the label personal media entered regular usage in the late 1970s when the personal computer was first being produced and plans were in the works to create even more personal (and portable) computing devices. Marika Lüders, “Conceptualizing Personal Media,” New Media and Society 10, no. 5 (2008): 684. The 1980s saw an explosion of personal media devices such as the Walkman, the VCR, the camcorder, the cell phone, and the personal computer. At this time, though, personal media devices lacked the connectivity that later allowed personal media to become social media. Still, during this time, people created personalized media environments that allowed for more control over the media messages with which they engaged. For example, while portable radios had been around for years, the Walkman allowed people to listen to any cassette tape they owned instead of having to listen to whatever the radio station played. Beyond that, people began creating mix tapes by recording their favorite songs from the radio or by dubbing select songs from other cassette tapes. Although a little more labor intensive, these mix tapes were the precursor to the playlists of digital music that we create today. Additionally, VCRs allowed people to watch specific movies on their own schedule rather than having to watch movies shown on television or at the movie theater.

While mass media messages are the creation of institutions and professionals, many personal media messages are the creation of individuals or small groups whose skills range from amateur to professional. Marika Lüders, “Conceptualizing Personal Media,” New Media and Society 10, no. 5 (2008): 683. Personal computers allowed amateurs and hobbyists to create new computer programs that they could circulate on discs or perhaps through early Internet connections. Camcorders allowed people to create a range of products from home videos to amateur or independent films. As was mentioned earlier, portable music recording and listening devices also allowed people to create their own mix tapes and gave amateur musicians an affordable and accessible way to make demo tapes. These amateur personal media creations weren’t as easily distributed as they are today, as the analogue technology still required that people send their messages on discs or tapes.

Personal media crossed the line to new and social media with the growing accessibility of the Internet and digital media. As media products like videos, music, and pictures turned digital, the analogue personal media devices that people once carried around were no longer necessary. New online platforms gave people the opportunity to create and make content that could be accessed by anyone with an Internet connection. For example, the singer who would have once sold demo tapes on cassettes out of his or her car might be now discovered after putting his or her music on MySpace.

Social Media

Media and mass media have long been discussed as a unifying force. The shared experience of national mourning after President Kennedy was assassinated and after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, was facilitated through media. Online media, in particular, is characterized by its connectivity. This type of connectivity is different from that of the mass media. Whereas a large audience was connected to the same radio or television broadcast, newspaper story, book, or movie via a one-way communication channel sent from one place to many, online media connects mass media outlets to people and allows people to connect back to them. The basis for this connectivity is the Internet, which connects individual computers, smartphones, and other devices in an interactive web, and it is this web of connected personal media devices like computers and smartphones that facilitates and defines social media. Technology has allowed for mediated social interaction since the days of the telegraph, but these connections were not at the mass level they are today. So even if we think of the telegram as a precursor to a “tweet,” we can still see that the potential connection points and the audience size are much different. While a telegraph went to one person, Olympian Michael Phelps can send a tweet instantly to 1.2 million people, and Justin Bieber’s tweets reach 23 million people! Social media doesn’t just allow for connection; it allows us more control over the quality and degree of connection that we maintain with others. Eugenia Siapera, Understanding New Media (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2012), 5.

The potential for social media was realized under the conditions of what is called Web 2.0, which refers to a new way of using the connectivity of the Internet to bring people together for collaboration and creativity—to harness collective intelligence. Tim O’Reilly, “What Is Web 2.0?” O’Reilly: Spreading the Knowledge of Innovators, accessed November 3, 2012, http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html. This entails using the web to collaborate on projects and problem solving rather than making and protecting one’s own material. Megan Boler, “Introduction,” in Digital Media and Democracy: Tactics in Hard Times, ed. Megan Boler (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 39. Much of this was achieved through platforms and websites such as Napster, Flickr, YouTube, and Wikipedia that encouraged and enable user-generated content. It is important to note that user-generated content and collaboration have been a part of the World Wide Web for decades, but much of it was in the form of self-publishing information such as user reviews, online journal entries/diaries, and later blogs, which cross over between the “old” web and Web 2.0.

The most influential part of the new web is social networking sites (SNSs), which allow users to build a public or semipublic profile, create a network of connections to other people, and view other people’s profiles and networks of connections. Danah M. Boyd and Nicole B. Ellison, “Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship,” Journal of Computer Mediated Communication 13, no. 1 (2008): 211. Although SNSs have existed for over a decade, earlier iterations such as Friendster and MySpace have given way to the giant that is Facebook. Facebook, which now has more than 955 million monthly active users is unquestionably the most popular SNS. “Key Facts,” Facebook Newsroom, accessed November 8, 2012, http://newsroom.fb.com/content/default.aspx?NewsAreaId=22. And the number of users is predicted to reach one billion by the end of 2012. Christy Hunter, “Number of Facebook Users Could Reach 1 Billion by 2012,” The Exponent Online, January 12, 2012, accessed November 8, 2012, http://www.purdueexponent.org/features/article_8815d757-8b7c-566f-8fbe-49528d4d8037 .html. More specific SNSs like LinkedIn focus on professional networking. In any case, the ability to self-publish information, likes/dislikes, status updates, profiles, and links allows people to craft their own life narrative and share it with other people. Likewise, users can follow the narratives of others in their network as they are constructed. The degree to which we engage with others’ narratives varies based on the closeness of the relationship and situational factors, but SNSs are used to sustain strong, moderate, and weak ties with others. Kathleen Richardson and Sue Hessey, “Archiving the Self?: Facebook as Biography of Social and Relational Memory,” Journal of Information, Communication, and Ethics in Society 7, no. 1 (2009): 29.

Let’s conceptualize social media in another way—through the idea of collaboration and sharing rather than just through interpersonal connection and interaction. The growth of open source publishing and creative commons licensing also presents a challenge to traditional media outlets and corporations and copyrights. Open source publishing first appeared most notably with software programs. The idea was that the users could improve on openly available computer programs and codes and then the new versions, sometimes called derivatives, would be made available again to the community. Crowdsourcing refers more to the idea stage of development where people from various perspectives and positions offer proposals or information to solve a problem or create something new. Daren C. Brabham, “Crowdsourcing as a Model for Problem Solving: An Introduction and Cases,” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14, no. 1 (2008): 76. This type of open access and free collaboration helps encourage participation and improve creativity through the synergy created by bringing together different perspectives and has been referred to as the biggest shift in innovation since the Industrial Revolution. Wendy Kaufman, “Crowd Sourcing Turns Business on Its Head,” NPR, August 20, 2008, accessed November 8, 2012, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=93495217. In short, the combination of open source publishing and crowdsourcing allows a community of users to collectively improve on and create more innovative ideas, products, and projects. Unlike most media products that are tightly copyrighted and closely monitored by the companies that create them, open source publishing and crowdsourcing increase the democratizing potential of new media.

The advent of these new, collaborative, participative, and democratizing media has been both resisted and embraced by old media outlets. Increased participation and feedback means that traditional media outlets that were used to one-way communication and passive audiences now have to listen to and respond to feedback, some of which is critical and/or negative. User-generated content, both amateur and professional, can also compete directly with traditional mass media content that costs much more to produce. Social media is responsible for the whole phenomenon of viral videos, through which a video of a kitten doing a flip or a parody of a commercial can reach many more audience members than a network video blooper show or an actual commercial. Media outlets are again in a paradox. They want to encourage audience participation, but they also want to be able to control and predict the media consumption habits and reactions of audiences. Eugenia Siapera, Understanding New Media (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2012), 56.

Key Takeaways

New media are distinct from old media in that they are less linked to a specific media platform and are therefore more transferable from device to device. They are also less bound to a physical object, meaning that information can be stored electronically rather than needing to be encoded onto a physical object.

New media are also distinct from old media in that they are more personal and social. As the line between consumers and producers of media blur in new media, users gain more freedom to personalize their media experiences. Additionally, the interactive web of personal media devices also allows people to stay in touch with each other, collaborate, and share information in ways that increase the social nature of technology use.

Exercises

Getting integrated: Identify some ways that you might use new media in each of the following contexts: academic, professional, personal, and civic.

How do you personalize the media that you use? How do digital media make it easier for you to personalize your media experiences than analogue media?

Aside from using social media to maintain interpersonal connections, how have you used social media to collaborate or share information?

16.2 New Media, the Self, and Relationships

Learning Objectives

Discuss the relationship between new media and the self.

Identify positive and negative impacts of new media on our interpersonal relationships.

Think about some ways that new media have changed the way you think about yourself and the way you think about and interact in your relationships. Have you ever given your Facebook page a “once-over” before you send or accept a friend request just to make sure that the content displayed is giving off the desired impression? The technological changes of the past twenty years have affected you and your relationships whether you are a heavy user or not. Even people who don’t engage with technology as much as others are still affected by it, since the people they interact with use and are affected by new media to varying degrees.

New Media and the Self

The explicit way we become conscious of self-presentation when using new media, social networking sites (SNSs) in particular, may lead to an increase in self-consciousness. You’ll recall that in Chapter 1 “Introduction to Communication Studies” we talked about the role that communication plays in helping us meet our identity needs and, in Chapter 2 “Communication and Perception”, the role that self-discrepancy theory plays in self-perception. The things that we “like” on Facebook, the pictures we are tagged in, and the news stories or jokes that we share on our timeline all come together to create a database of information that new and old friends can access to form and reform impressions of us. Because we know that others are making impressions based on this database of information and because we have control over most of what appears in this database, people may become overfocused on crafting their online presence to the point that they neglect their offline relationships. This extra level of self-consciousness has also manifested in an increase in self-image and self-esteem issues for some users. For example, some cosmetic surgeons have noted an uptick in patients coming in to have facial surgeries or procedures specifically because they don’t like the way their chin looks on the webcam while chatting on Skype or because they feel self-conscious about the way they look in the numerous digital pictures that are now passed around and stored on new media. Since new media are being increasingly used in professional capacities, some people are also seeking cosmetic surgery or procedures as a way of investing in their personal brand or as a way of giving them an edge in a tight job market. Jessica Roy, “Facebook, Skype Give Cosmetic Surgery Industry a Lift,” BetaBeat.com, July 11, 2012, accessed November 8, 2012, http://betabeat.com/2012/07/facebook-skype-plastic-surgery-cosmetic-increase-07112012.

The personal and social nature of new media also creates an openness that isn’t necessarily part of our offline social reality. Although some people try to address this problem by creating more than one Facebook account, according to the terms of use we all agreed to, we are not allowed to create more than one personal profile. People may also have difficulty managing their different commitments, especially if they develop a dependence on or even addiction to new media devices and/or platforms. New media blur the lines between personal and professional in many ways, which can be positive and negative. For example, the constant connection offered by laptops and smartphones increases the expectation that people will continue working from home or while on vacation. At the same time, however, people may use new media for non-work-related purposes while at work, which may help even out the work/life balance. Cyberslacking, which is the non-work-related use of new media while on the job, is seen as a problem in many organizations and workplaces. However, some research shows that occasional use of new media for personal reasons while at work can have positive effects, as it may relieve boredom, help reduce stress, or lead to greater job satisfaction. Jessica Vitak, Julia Crouse, and Robert LaRose, “Personal Internet Use at Work: Understanding Cyberslacking,” Computers in Human Behavior 27, no. 5 (2011): 1752.

Pexel.com – CC0 public domain.

Personal media devices bring with them a sense of constant connectivity that makes us “reachable” nearly all the time and can be comforting or anxiety inducing. Devices such as smartphones and computers, and platforms such as e-mail, Facebook, and the web, are within an arm’s reach of many people. While this can be convenient and make things more efficient in some cases, it can also create a dependence that we might not be aware of until those connections are broken or become unreliable. You don’t have to look too far to see people buried in their smartphones, tablets, or laptops all around. While some people have learned to rely on peripheral vision in order to text and walk at the same time, others aren’t so graceful. In fact, London saw the creation of a “text safe” street with padding on street signs and lamp poles to help prevent injuries when people inevitably bump into them while engrossed in their gadgets’ screens. Follow this link to read a story in Time magazine and see a picture of the street: http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1724522,00.html. Additionally, a survey conducted in the United Kingdom found that being away from social networks causes more anxiety than being a user of them. Another study found that 73 percent of people would panic if they lost their smartphone. Brittney Fitzgerald, “Social Media Is Causing Anxiety, Study Finds,” Huffington Post, July 11, 2012, accessed November 8, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/07/10/social-media-anxiety_n_1662224.html.

Of course, social media can also increase self-esteem or have other social benefits. A recent survey of fifteen thousand women found that 48 percent of the respondents felt that social media helped them stay in touch with others while also adding a little stress in terms of overstimulation. Forty-two percent didn’t mention the stress of overstimulation and focused more on the positive effects of being in touch with others and the world in general. When asked about how social media affects their social lives, 30 percent of the women felt that increased use of social media helped them be more social offline as well. Bonnie Kintzer, “Women Find Social Media Make Them More Social Offline, Too,” Advertising Age, July 9, 2012, accessed November 8, 2012, http://adage.com/article/guest-columnists/women-find-social-media-makes-social-offline/235712. Other research supports this finding for both genders, finding that Facebook can help people with social anxiety feel more confident and socially connected. Tracii Ryan and Sophia Xenos, “Who Uses Facebook? An Investigation into the Relationship between the Big Five, Shyness, Narcissism, Loneliness, and Facebook Usage,” Computers in Human Behavior 27, no. 5 (2011): 1659.

Your Online Identity

Adapted from — Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

https://milneopentextbooks.org/interpersonal-communication-a-mindful-approach-to-relationships/

In the earliest days of the Internet, it was common for people to be completely anonymous on the Internet (more on this in a minute). For our purposes, it’s important to realize that different people present themselves differently in CMC contexts. For example, someone chatting with a complete stranger on Tinder may act one way and then act completely differently when texting with her/his/their mother.

Erving Goffman and Identity

Erving Goffman, in his book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, was the first to note that when interacting with others, people tended to guide or control the presentation of themselves to the other person.1 As people, we can alter how we look (to a degree), how we behave, and how we communicate, and all of these will impact the perception that someone builds of us during an interaction. So, while we’re attempting to create an impression of ourselves, the other person is also attempting to create a perception of who you are as a person at the same time.

In an ideal world, how we hope we’re presenting ourselves will be how the other person interprets this self-presentation, but it doesn’t always work out that way. Goffman coined this type of interactive sensemaking the dramaturgical analysis because he saw the faces people put when interacting with others as similar to roles actors put in on a play. In this respect, Goffman used the term “front stage” to the types of behavior we exhibit when we know others are watching us (e.g., an interpersonal interaction). “Backstage” then is the behavior we engage in when we have no audience present, so we are free from the rules and norms of interaction that govern our day-to-day interactions with others. Basically, we can let our hair down and relax by taking off the character we perform on stage. At the same time, we also prepare for future interactions on stage while we’re backstage. For example, maybe a woman will practice a pick up line she plans on using in a bar after work, or a guy will rehearse what he’s going to say when he meets his boyfriend’s parents at dinner that night.

Erving Goffman died in 1982 well before the birth of the WWW and the Internet as most of us know it today, so he didn’t write about the issue of online identities. Syed Murtaza Alfarid Hussain applied Goffman’s dramaturgical approach to Facebook.2 Alfarid Hussain argues that Facebook can be seen as part of the “front stage” for interaction where we perform our identities. As such, Facebook “provides the opportunity for individuals to use props such as user profile information, photo posting/sharing/tagging, status updates, ‘Like’ and ‘Unlike’ others posts, comments or wall posts, profile image/cover page image, online befriending, group/community membership, weblinks and security and privacy settings.”3 If you’re like us, maybe sat in front of your smartphone, tablet computer, laptop, or desktop computer and wanted to share a meme, but realized that many people you’re friends with on Facebook wouldn’t find the meme humorous, so you don’t share the meme. When you do this, you are negotiating your identity on stage. You are determining and influencing how others will view you through the types of posts you make, the shares you make, and even the likes you give to others’ posts.

In another study examining identity in blogging and the online 3D multiverse SecondLife, Liam Bullingham and Ana C. Vasconcelos found that most people who blog and those who participated on SecondLife (in their study) “were keen to re-create their offline self online. This was achieved by creating a blogging voice that is true to the offline one, and by publishing personal details about the offline self online, or designing the avatar to resemble the offline self in SL, and in disclosing offline identity in SL.”4 In “Goffman-speak,” people online attempt to mimic their onstage performances across different mediums. Now clearly, not everyone who blogs and hangs out in SecondLife will do this, but the majority of the individuals in Bullingham and Vasconcelos’ study did. The authors noted differences between bloggers and SL users. Specifically, SL users have:

more obvious options to deviate from the offline self and adopt personae in terms of the appearance of the 3D avatar. In blogging, it is perhaps expected that persona adoption does not occur, unless a detachment from the offline self is obvious, such as in the case of pseudonymous blogging. Also, the nature of interaction is different, with blogging resembling more closely platform performances and the SL environment offering more opportunities for contacts and encounters.5

Types of Online Identities

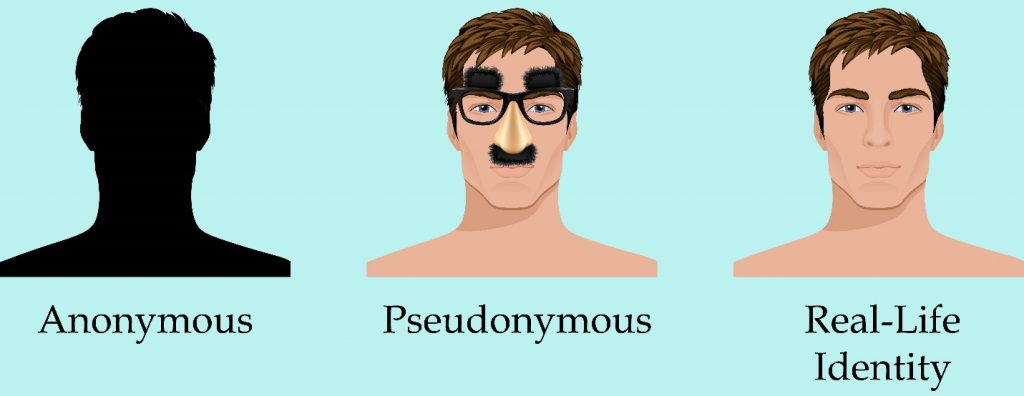

Unlike traditional FtF interactions, online interactions can go even further blurring the identities as people act in ways impossible in FtF interaction. Andrew F. Wood and Matthew J. Smith discussed three different ways that people express their identities online: anonymity, pseudonymity, and real-life (Figure 12.9).6

Anonymous Identity

First, people in a CMC context can behavior in a way that is completely anonymous. In this case, people in CMC interactions can communicate in a manner where their actual identity is simply not known. Now, it may be possible for some people to figure out who an anonymous person is (e.g., the NSA, the CIA, etc.), but if someone wants to maintain her or his anonymity, it’s possible to do so. Think about how many fake Facebook, Twitter, Tinder, Grindr accounts exist. Some exist to try to persuade you to go to a website (often for illicit purposes like hacking your computer), while others may be attempting “catfishing” for the fun of it.

Catfishing is a deceptive activity perpetrated by Internet predators where they fabricate online identities on social networking sites to lure unsuspecting victims into an emotional/romantic relationship. In the 2010 documentary Catfish, we are introduced Yaniv “Nev” Schulman, a New York-based photographer, who starts an online relationship with an 8-year-old prodigy named Abby via Facebook. Over the course of nine months, the two exchange more than 1,500 messages, and Abby’s family (mother, father, and sister) also become friends with Nev on Facebook as well. Throughout the documentary, Nev and his brother Ariel (who is also the documentarian) start noticing inconsistencies in various stories that are being told. Music that was allegedly created by Abby is found to be right off of YouTube. Ariel convinces Nev to continue the relationship knowing that there are inconsistencies and lies just to see how it will all play out. The success of Catfish spawned a television show by the same name on MTV.

From this one story, we can easily see the problems that can arise from anonymity on the Internet. Often behavior that would be deemed completely inappropriate in a FtF encounter suddenly becomes appropriate because it’s deemed as “less real” by some. One of the major problems with anonymity online has been cyberbullying. Teenagers today can post horrible things about one another online without any worry that the messages will be linked back to them directly. Unlike bullying that happened at school, teens facing cyberbullying cannot even find peace at home because the Internet follows them everywhere. In 2013 12-year-old Rebecca Ann Sedwick committed suicide after being the perpetual victim of cyberbullying through social media apps on her phone. Some of the messages found on her phone after her suicide included, “why are you still alive?” and “you haven’t killed yourself yet? Go jump off a building.” Rebecca suffered this barrage of bullying for over a year and by around 15 different girls in her school. Sadly, Rebecca’s tale is one that is all too familiar in today’s world. Although only 9% of middle-school age kids have reported being victims of cyberbullying, there is a relationship between victimization and suicidal ideation.7

It’s also important to understand that cyberbullying isn’t just a phenomenon that happens with children. In a 2009 survey of Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union members, they found that 34% of respondents faced FtF bullying, and 10.7% faced cyberbullying. All of the individuals who were targets of cyberbullying were also ones bullied FtF.8

Many people prefer anonyms when interacting with others online, and there can be legitimate reasons to engage in online interactions with others. For example, when one of our authors was coming out as LGBTQIA, our coauthor regularly talked with people online as our coauthor melded the new LGBTQIA identity with their Southern/Christian identity. Having the ability to talk anonymously with others allowed our coauthor to gradually come out by forming anonymous relationships with others dealing with the same issues.

Pseudonymous Identity

Second, the second category of interaction is pseudonymity CMC identity. Wood and Smith used the term pseudonymous because of the prefix “pseudonym,” “Pseudonym comes from the Latin words for ‘false’ and ‘name,’ and it provides an audience with the ability to attribute statements and actions to a common source [emphasis in original].”9 Whereas an anonym allows someone to be completely anonymous, a pseudonym “allows one to contribute to the fashioning of one’s own image.”10

Using pseudonyms is hardly something new. Famed mystery author Agatha Christi wrote over 66 detective novels, but still published six romance novels using the pseudonym Mary Westmacott. Bestselling science fiction author Michael Crichton (of Jurassic Park fame – among others), wrote under three different pseudonyms (John Lange, Jeffery Hudson, and Michael Douglas) when he was in medical school. Even J. K. Rowling (of Harry Potter fame) used the pseudonym Robert Galbraith to write her follow-up novel to the series. Rowling didn’t want the hype or expectation while writing her follow-up novel. Unfortunately for Rowling, the secret didn’t stay hidden very long.

There are many famous people who use pseudonyms in their social media: @TheTweetOfGod (comedy writer and Daily Show producer, David Javerbaum), @pewdiepie (online personality and producer Felix Arvid Ulf Kjellberg), @baddiewinkle (Octogenarian fashionista and online personality Helen Van Winkle), @doctor.mike (Internet celebrity family practitioner Dr. Mike Varshavski), etc…. Some of these people used parts of their real names, and others used complete pseudonyms. All of them have enormous Internet followings and have used their pseudonyms to build profitable brands. So, why do people use a pseudonym?

The veneer of the Internet allows us to determine how much of an identity we wish to front in online presentations. These images can range from a vague silhouette to a detailed snapshot. Whatever the degree of identity presented, however, it appears that control and empowerment are benefits for users of these communication technologies.11

Now, some people adopt a pseudonym because their online actions may be “out of brand” for their day-job or because they don’t want to be fully exposed online.

Real Life Identity

Lastly, some people have their real-life identities displayed online. You can find JasonSWrench on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc…. Our coauthor made the decision to have his social networking site behavior very public from the beginning. Part of that reason was that when he first joined Facebook in 2007, he was required to use his professional school email address that ended with.edu. In the early days, only people with.edu email addresses could join Facebook. Jason also realizes that this behavior is a part of his professional persona, so he doesn’t put anything on one of these sites he wouldn’t want other professionals (or even you) to see and read. When it comes to people in the public eye, most of them use some variation of their real names to enhance their brands. That’s not to say that many of these same people may have multiple online accounts, and some of these accounts could be completely anonymous or even pseudonymous.

1 Goffman, E, (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books.

2 Alfarid Hussain, S. M. (2015). Presentation of self among social media users in Assam: Appropriating Goffman to Facebook users’ engagement with online communities. Global Media Journal: Indian Edition, 6(1&2), 1–14. https://tinyurl.com/sbbll8a

3 Alfarid Hussain, S. M. (2015). Presentation of self among social media users in Assam: Appropriating Goffman to Facebook users’ engagement with online communities. Global Media Journal: Indian Edition, 6(1&2), 1–14. https://tinyurl.com/sbbll8a; pg. 3.

4 Bullingham, L., & Vasconcelos, A. C. (2013). “The presentation of self in the online world:” Goffman and the study of online identities. Journal of Information Science, 39(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551512470051; pg. 110.

5 Bullingham, L., & Vasconcelos, A. C. (2013). “The presentation of self in the online world:” Goffman and the study of online identities. Journal of Information Science, 39(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551512470051; pg. 110.

6 Wood, A. F., & Smith, M. J. (2005). Online communication: Linking technology, identity, & culture (2nd ed.). Routledge.

7 Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2010). Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 14, 206-221.

8 Privitera, C. (2009). Cyberbullying: The new face of workplace bullying? Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(4), 395-400. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2009.0025

9 Wood, A. F., & Smith, M. J. (2005). Online communication: Linking technology, identity, & culture (2nd ed.). Routledge; pg. 64.

10 Wood, A. F., & Smith, M. J. (2005). Online communication: Linking technology, identity, & culture (2nd ed.). Routledge; pg. 66.

11 Wood, A. F., & Smith, M. J. (2005). Online communication: Linking technology, identity, & culture (2nd ed.). Routledge; pgs. 66-67.

New Media and Interpersonal Relationships

How do new media affect our interpersonal relationships, if at all? This is a question that has been addressed by scholars, commentators, and people in general. To provide some perspective, similar questions and concerns have been raised along with each major change in communication technology. New media, however, have been the primary communication change of the past few generations, which likely accounts for the attention they receive. Some scholars in sociology have decried the negative effects of new technology on society and relationships in particular, saying that the quality of relationships is deteriorating and the strength of connections is weakening. Kathleen Richardson and Sue Hessey, “Archiving the Self?: Facebook as Biography of Social and Relational Memory,” Journal of Information, Communication, and Ethics in Society 7, no. 1 (2009): 29.

Facebook greatly influenced our use of the word friend, although people’s conceptions of the word may not have changed as much. When someone “friends you” on Facebook, it doesn’t automatically mean that you now have the closeness and intimacy that you have with some offline friends. And research shows that people don’t regularly accept friend requests from or send them to people they haven’t met, preferring instead to have met a person at least once. Kathleen Richardson and Sue Hessey, “Archiving the Self?: Facebook as Biography of Social and Relational Memory,” Journal of Information, Communication, and Ethics in Society 7, no. 1 (2009): 32. Some users, though, especially adolescents, engage in what is called “friend-collecting behavior,” which entails users friending people they don’t know personally or that they wouldn’t talk to in person in order to increase the size of their online network. Emily Christofides, Amy Muise, and Serge Desmarais, “Hey Mom, What’s on Your Facebook? Comparing Facebook Disclosure and Privacy in Adolescents and Adults,” Social Psychological and Personality Science 3, no. 1 (2012): 51. As we will discuss later, this could be an impression management strategy, as the user may assume that a large number of Facebook friends will make him or her appear more popular to others.

Although many have critiqued the watering down of the term friend when applied to SNSs, specifically Facebook, some scholars have explored how the creation of these networks affects our interpersonal relationships and may even restructure how we think about our relationships. Even though a person may have hundreds of Facebook friends that he or she doesn’t regularly interact with on- or offline, just knowing that the network exists in a somewhat tangible form (catalogued on Facebook) can be comforting. Even the people who are distant acquaintances but are “friends” on Facebook can serve important functions. Rather than Facebook users seeing these connections as pointless, frivolous, or stressful, they are often comforting background presences. A dormant network is a network of people with whom users may not feel obligated to explicitly interact but may find comfort in knowing the connections exist. Such networks can be beneficial, because when needed, a person may be able to more easily tap into that dormant network than they would an offline extended network. It’s almost like being friends on Facebook keeps the communication line open, because both people can view the other’s profile and keep up with their lives even without directly communicating. This can help sustain tenuous friendships or past friendships and prevent them from fading away, which as we learned in Chapter 7 “Communication in Relationships” is a common occurrence as we go through various life changes.

A key part of interpersonal communication is impression management, and some forms of new media allow us more tools for presenting ourselves than others. Social networking sites (SNSs) in many ways are platforms for self-presentation. Even more than blogs, web pages, and smartphones, the environment on an SNS like Facebook or Twitter facilitates self-disclosure in a directed way and allows others who have access to our profile to see our other “friends.” This convergence of different groups of people (close friends, family, acquaintances, friends of friends, colleagues, and strangers) can present challenges for self-presentation. Although Facebook is often thought of as a social media outlet for teens and young adults, research shows half of all US adults have a profile on Facebook or another SNS. Jessica Vitak and Nicole B. Ellison, “‘There’s a Network Out There You Might as Well Tap’: Exploring the Benefits of and Barriers to Exchanging Informational and Support-Based Resources on Facebook,” New Media and Society (in press). The fact that Facebook is expanding to different generations of users has coined a new phrase—“the graying of Facebook.” This is due to a large increase in users over the age of fifty-five. In fact, it has been stated the fastest-growing Facebook user group is women fifty-five and older, which is up more than 175 percent since fall 2008. Anita Gates, “For Baby Boomers, the Joys of Facebook,” New York Times, March 19, 2009, accessed November 8, 2012,http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/22/nyregion/new-jersey/22Rgen.html. So now we likely have people from personal, professional, and academic contexts in our Facebook network, and those people are now more likely than ever to be from multiple generations. The growing diversity of our social media networks creates new challenges as we try to engage in impression management.

We should be aware that people form impressions of us based not just on what we post on our profiles but also on our friends and the content that they post on our profiles. In short, as in our offline lives, we are judged online by the company we keep. Joseph B. Walther, Brandon Van Der Heide, Sang-Yeon Kim, David Westerman, and Stephanie Tom Tong, “The Role of Friends’ Appearance and Behavior on Evaluations of Individuals on Facebook: Are We Known by the Company We Keep?” Human Communication Research 34 (2008): 29. The difference is, though, that via Facebook a person (unless blocked or limited by privacy settings) can see our entire online social network and friends, which doesn’t happen offline. The information on our Facebook profiles is also archived, meaning there is a record the likes of which doesn’t exist in offline interactions. Recent research found that a person’s perception of a profile owner’s attractiveness is influenced by the attractiveness of the friends shown on the profile. In short, a profile owner is judged more physically attractive when his or her friends are judged as physically attractive, and vice versa. The profile owner is also judged as more socially attractive (likable, friendly) when his or her friends are judged as physically attractive. The study also found that complimentary and friendly statements made about profile owners on their wall or on profile comments increased perceptions of the profile owner’s social attractiveness and credibility. An interesting, but not surprising, gender double standard also emerged. When statements containing sexual remarks or references to the profile owner’s excessive drinking were posted on the profile, perceptions of attractiveness increased if the profile owner was male and decreased if female. Joseph B. Walther, Brandon Van Der Heide, Sang-Yeon Kim, David Westerman, and Stephanie Tom Tong, “The Role of Friends’ Appearance and Behavior on Evaluations of Individuals on Facebook: Are We Known by the Company We Keep?” Human Communication Research 34 (2008): 41–45.

Self-disclosure is a fundamental building block of interpersonal relationships, and new media make self-disclosures easier for many people because of the lack of immediacy, meaning the fact that a message is sent through electronic means arouses less anxiety or inhibition than would a face-to-face exchange. SNSs provide opportunities for social support. Research has found that Facebook communication behaviors such as “friending” someone or responding to a request posted on someone’s wall lead people to feel a sense of attachment and perceive that others are reliable and helpful. Jessica Vitak and Nicole B. Ellison, “‘There’s a Network Out There You Might as Well Tap’: Exploring the Benefits of and Barriers to Exchanging Informational and Support-Based Resources on Facebook,” New Media and Society (in press). Much of the research on Facebook, though, has focused on the less intimate alliances that we maintain through social media. Since most people maintain offline contact with their close friends and family, Facebook is more of a supplement to interpersonal communication. Since most people’s Facebook “friend” networks are composed primarily of people with whom they have less face-to-face contact in their daily lives, Facebook provides an alternative space for interaction that can more easily fit into a person’s busy schedule or interest area. For example, to stay connected, both people don’t have to look at each other’s profiles simultaneously. I often catch up on a friend by scrolling through a couple weeks of timeline posts rather than checking in daily.

The space provided by SNSs can also help reduce some of the stress we feel in regards to relational maintenance or staying in touch by allowing for more convenient contact. The expectations for regular contact with our Facebook friends who are in our extended network are minimal. An occasional comment on a photo or status update or an even easier click on the “like” button can help maintain those relationships. However, when we post something asking for information, help, social support, or advice, those in the extended network may play a more important role and allow us to access resources and viewpoints beyond those in our closer circles. And research shows that many people ask for informational help through their status updates. Jessica Vitak and Nicole B. Ellison, “‘There’s a Network Out There You Might as Well Tap’: Exploring the Benefits of and Barriers to Exchanging Informational and Support-Based Resources on Facebook,” New Media and Society (in press).

These extended networks serve important purposes, one of which is to provide access to new information and different perspectives than those we may get from close friends and family. For example, since we tend to have significant others that are more similar to than different from us, the people that we are closest to are likely to share many or most of our beliefs, attitudes, and values. Extended contacts, however, may expose us to different political views or new sources of information, which can help broaden our perspectives. The content in this section hopefully captures what I’m sure you have already experienced in your own engagement with new media—that new media have important implications for our interpersonal relationships. Given that, we will end this chapter with a “Getting Competent” feature box that discusses some tips on how to competently use social media.

“Getting Competent”

Using Social Media Competently

We all have a growing log of personal information stored on the Internet, and some of it is under our control and some of it isn’t. We also have increasingly diverse social networks that require us to be cognizant of the information we make available and how we present ourselves. While we can’t control all the information about ourselves online or the impressions people form, we can more competently engage with social media so that we are getting the most out of it in both personal and professional contexts.

A quick search on Google for “social media dos and don’ts” will yield around 100,000 results, which shows that there’s no shortage of advice about how to competently use social media. I’ll offer some of the most important dos and don’ts that I found that relate to communication. Alison Doyle, “Top 10 Social Media Dos and Don’ts,” About.com, accessed November 8, 2012, http://jobsearch.about.com/od/onlinecareernetworking/tp/socialmediajobsearch.htm. Feel free to do your own research on specific areas of concern.

Be consistent. Given that most people have multiple social media accounts, it’s important to have some degree of consistency. At least at the top level of your profile (the part that isn’t limited by privacy settings), include information that you don’t mind anyone seeing.

Know what’s out there. Since the top level of many social media sites are visible in Google search results, you should monitor how these appear to others by regularly (about once a month) doing a Google search using various iterations of your name. Putting your name in quotation marks will help target your results. Make sure you’re logged out of all your accounts and then click on the various results to see what others can see.

Think before you post. Software that enable people to take “screen shots” or download videos and tools that archive web pages can be used without our knowledge to create records of what you post. While it is still a good idea to go through your online content and “clean up” materials that may form unfavorable impressions, it is even a better idea to not put that information out there in the first place. Posting something about how you hate school or your job or a specific person may be done in the heat of the moment and forgotten, but a potential employer might find that information and form a negative impression even if it’s months or years old.

Be familiar with privacy settings. If you are trying to expand your social network, it may be counterproductive to put your Facebook or Twitter account on “lockdown,” but it is beneficial to know what levels of control you have and to take advantage of them. For example, I have a “Limited Profile” list on Facebook to which I assign new contacts or people with whom I am not very close. You can also create groups of contacts on various social media sites so that only certain people see certain information.

Be a gatekeeper for your network. Do not accept friend requests or followers that you do not know. Not only could these requests be sent from “bots” that might skim your personal info or monitor your activity; they could be from people that might make you look bad. Remember, we learned earlier that people form impressions based on those with whom we are connected. You can always send a private message to someone asking how he or she knows you or do some research by Googling his or her name or username.

Identify information that you might want to limit for each of the following audiences: friends, family, and employers.

Google your name (remember to use multiple forms and to put them in quotation marks). Do the same with any usernames that are associated with your name (e.g., you can Google your Twitter handle or an e-mail address). What information came up? Were you surprised by anything?

What strategies can you use to help manage the impressions you form on social media?

Key Takeaways

New media affect interpersonal relationships, as conceptions of relationships are influenced by new points of connection such as “being Facebook friends.” While some people have critiqued social media for lessening the importance of face-to-face interaction, some communication scholars have found that online networks provide important opportunities to stay connected, receive emotional support, and broaden our perspectives in ways that traditional offline networks do not.

Getting integrated: Social networking sites (SNSs) can present interpersonal challenges related to self-disclosure and self-presentation since we use them in academic, professional, personal, and civic contexts. Given that people from all those contexts may have access to our profile, we have to be competent in regards to what we disclose and how we present ourselves to people from different contexts (or be really good at managing privacy settings so that only certain information is available to certain people).

Exercises

Discuss the notion that social media has increased our degree of self-consciousness. Do you agree? Why or why not?

Do you find the constant connectivity that comes with personal media overstimulating or comforting?

Have you noticed a “graying” of social media like Facebook and Twitter in your own networks? What opportunities and challenges are presented by intergenerational interactions on social media?