Chapter 6 – Interpersonal Communication Processes

Taking an interpersonal communication course as an undergraduate is what made me change my major from music to communication studies. I was struck by the clear practicality of key interpersonal communication concepts in my everyday life and in my relationships. I found myself thinking, “Oh, that’s what it’s called!” or “My mom does that to me all the time!” I hope that you will have similar reactions as we learn more about how we communicate with the people in our daily lives.

6.1 Principles of Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

Define interpersonal communication.

Discuss the functional aspects of interpersonal communication.

Discuss the cultural aspects of interpersonal communication.

In order to understand interpersonal communication, we must understand how interpersonal communication functions to meet our needs and goals and how our interpersonal communication connects to larger social and cultural systems. Interpersonal communication is the process of exchanging messages between people whose lives mutually influence one another in unique ways in relation to social and cultural norms. This definition highlights the fact that interpersonal communication involves two or more people who are interdependent to some degree and who build a unique bond based on the larger social and cultural contexts to which they belong. So a brief exchange with a grocery store clerk who you don’t know wouldn’t be considered interpersonal communication, because you and the clerk are not influencing each other in significant ways. Obviously, if the clerk were a friend, family member, coworker, or romantic partner, the communication would fall into the interpersonal category. In this section, we discuss the importance of studying interpersonal communication and explore its functional and cultural aspects.

Why Study Interpersonal Communication?

Interpersonal communication has many implications for us in the real world. Did you know that interpersonal communication played an important role in human evolution? Early humans who lived in groups, rather than alone, were more likely to survive, which meant that those with the capability to develop interpersonal bonds were more likely to pass these traits on to the next generation. Mark R. Leary, “Toward a Conceptualization of Interpersonal Rejection,” in Interpersonal Rejection, ed. Mark R. Leary (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 3–20. Did you know that interpersonal skills have a measurable impact on psychological and physical health? People with higher levels of interpersonal communication skills are better able to adapt to stress, have greater satisfaction in relationships and more friends, and have less depression and anxiety. Owen Hargie, Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (London: Routledge, 2011), 2. In fact, prolonged isolation has been shown to severely damage a human. Kipling D. Williams and Lisa Zadro, “Ostracism: On Being Ignored, Excluded, and Rejected,” in Interpersonal Rejection, ed. Mark R. Leary (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 21–54. Have you ever heard of the boy or girl who was raised by wolves? There have been documented cases of abandoned or neglected children, sometimes referred to as feral children, who survived using their animalistic instincts but suffered psychological and physical trauma as a result of their isolation. Douglas K. Candland, Feral Children and Clever Animals: Reflections on Human Nature (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995). There are also examples of solitary confinement, which has become an ethical issue in many countries. In “supermax” prisons, which now operate in at least forty-four states, prisoners spend 22.5 to 24 hours a day in their cells and have no contact with the outside world or other prisoners. Sharon Shalev, “Solitary Confinement and Supermax Prisons: A Human Rights and Ethical Analysis,” Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice 11, no. 2 (2011): 151.

Aside from making your relationships and health better, interpersonal communication skills are highly sought after by potential employers, consistently ranking in the top ten in national surveys. National Association of Colleges and Employers, Job Outlook 2011 (2010): 25. Each of these examples illustrates how interpersonal communication meets our basic needs as humans for security in our social bonds, health, and careers. But we are not born with all the interpersonal communication skills we’ll need in life. So in order to make the most out of our interpersonal relationships, we must learn some basic principles.

Think about a time when a short communication exchange affected a relationship almost immediately. Did you mean for it to happen? Many times we engage in interpersonal communication to fulfill certain goals we may have, but sometimes we are more successful than others. This is because interpersonal communication is strategic, meaning we intentionally create messages to achieve certain goals that help us function in society and our relationships. Goals vary based on the situation and the communicators, but ask yourself if you are generally successful at achieving the goals with which you enter a conversation or not. If so, you may already possess a high degree of interpersonal communication competence, or the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in personal relationships. This chapter will help you understand some key processes that can make us more effective and appropriate communicators. You may be asking, “Aren’t effectiveness and appropriateness the same thing?” The answer is no. Imagine that you are the manager of a small department of employees at a marketing agency where you often have to work on deadlines. As a deadline approaches, you worry about your team’s ability to work without your supervision to complete the tasks, so you interrupt everyone’s work and assign them all individual tasks and give them a bulleted list of each subtask with a deadline to turn each part in to you. You meet the deadline and have effectively accomplished your goal. Over the next month, one of your employees puts in her two-weeks’ notice, and you learn that she and a few others have been talking about how they struggle to work with you as a manager. Although your strategy was effective, many people do not respond well to strict hierarchy or micromanaging and may have deemed your communication inappropriate. A more competent communicator could have implemented the same detailed plan to accomplish the task in a manner that included feedback, making the employees feel more included and heard. In order to be competent interpersonal communicators, we must learn to balance being effective and appropriate.

Functional Aspects of Interpersonal Communication

We have different needs that are met through our various relationships. Whether we are aware of it or not, we often ask ourselves, “What can this relationship do for me?” In order to understand how relationships achieve strategic functions, we will look at instrumental goals, relationship-maintenance goals, and self-presentation goals.

What motivates you to communicate with someone? We frequently engage in communication designed to achieve instrumental goals such as gaining compliance (getting someone to do something for us), getting information we need, or asking for support. Brant R. Burleson, Sandra Metts, and Michael W. Kirch, “Communication in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 247. In short, instrumental talk helps us “get things done” in our relationships. Our instrumental goals can be long term or day to day. The following are examples of communicating for instrumental goals:

- You ask your friend to help you move this weekend (gaining/resisting compliance).

- You ask your coworker to remind you how to balance your cash register till at the end of your shift (requesting or presenting information).

- You console your roommate after he loses his job (asking for or giving support).

When we communicate to achieve relational goals, we are striving to maintain a positive relationship. Engaging in relationship-maintenance communication is like taking your car to be serviced at the repair shop. To have a good relationship, just as to have a long-lasting car, we should engage in routine maintenance. For example, have you ever wanted to stay in and order a pizza and watch a movie, but your friend suggests that you go to a local restaurant and then to the theatre? Maybe you don’t feel like being around a lot of people or spending money (or changing out of your pajamas), but you decide to go along with his or her suggestion. In that moment, you are putting your relational partner’s needs above your own, which will likely make him or her feel valued. It is likely that your friend has made or will also make similar concessions to put your needs first, which indicates that there is a satisfactory and complimentary relationship. Obviously, if one partner always insists on having his or her way or always concedes, becoming the martyr, the individuals are not exhibiting interpersonal-communication competence. Other routine relational tasks include celebrating special occasions or honoring accomplishments, spending time together, and checking in regularly by phone, e-mail, text, social media, or face-to-face communication. The following are examples of communicating for relational goals:

- You organize an office party for a coworker who has just become a US citizen (celebrating/honoring accomplishments).

- You make breakfast with your mom while you are home visiting (spending time together).

- You post a message on your long-distance friend’s Facebook wall saying you miss him (checking in).

Another form of relational talk that I have found very useful is what I call the DTR talk, which stands for “defining-the-relationship talk” and serves a relationship-maintenance function. In the early stages of a romantic relationship, you may have a DTR talk to reduce uncertainty about where you stand by deciding to use the term boyfriend, girlfriend, or partner. In a DTR talk, you may proactively define your relationship by saying, “I’m glad I’m with you and no one else.” Your romantic interest may respond favorably, echoing or rephrasing your statement, which gives you an indication that he or she agrees with you. The talk may continue on from there, and you may talk about what to call your relationship, set boundaries, or not. It is not unusual to have several DTR talks as a relationship progresses. At times, you may have to define the relationship when someone steps over a line by saying, “I think we should just be friends.” This more explicit and reactive (rather than proactive) communication can be especially useful in situations where a relationship may be unethical, inappropriate, or create a conflict of interest—for example, in a supervisor-supervisee, mentor-mentee, professional-client, or collegial relationship.

We also pursue self-presentation goals by adapting our communication in order to be perceived in particular ways. Just as many companies, celebrities, and politicians create a public image, we desire to present different faces in different contexts. The well-known scholar Erving Goffman compared self-presentation to a performance and suggested we all perform different roles in different contexts. Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (New York: Anchor Books, 1959). Indeed, competent communicators can successfully manage how others perceive them by adapting to situations and contexts. A parent may perform the role of stern head of household, supportive shoulder to cry on, or hip and culturally aware friend to his or her child. A newly hired employee may initially perform the role of serious and agreeable coworker. Sometimes people engage in communication that doesn’t necessarily present them in a positive way. For example, Haley, the oldest daughter in the television show Modern Family, often presents herself as incapable in order to get her parents to do her work. In one episode she pretended she didn’t know how to crack open an egg so her mom Claire would make the brownies for her school bake sale. Here are some other examples of communicating to meet self-presentation goals:

- As your boss complains about struggling to format the company newsletter, you tell her about your experience with Microsoft Word and editing and offer to look over the newsletter once she’s done to fix the formatting (presenting yourself as competent).

- You and your new college roommate stand in your dorm room full of boxes. You let him choose which side of the room he wants and then invite him to eat lunch with you (presenting yourself as friendly).

- You say, “I don’t know,” in response to a professor’s question even though you have an idea of the answer (presenting yourself as aloof, or “too cool for school”).

As if managing instrumental, relational, and self-presentation goals isn’t difficult enough when we consider them individually, we must also realize that the three goal types are always working together. In some situations we may privilege instrumental goals over relational or self-presentation goals. For example, if your partner is offered a great job in another state and you decided to go with him or her, which will move you away from your job and social circle, you would be focusing on relational goals over instrumental or self-presentation goals. When you’re facing a stressful situation and need your best friend’s help and call saying, “Hurry and bring me a gallon of gas or I’m going to be late to work!” you are privileging instrumental goals over relational goals. Of course, if the person really is your best friend, you can try to smooth things over or make up for your shortness later. However, you probably wouldn’t call your boss and bark a request to bring you a gallon of gas so you can get to work, because you likely want your boss to see you as dependable and likable, meaning you have focused on self-presentation goals.

The functional perspective of interpersonal communication indicates that we communicate to achieve certain goals in our relationships. We get things done in our relationships by communicating for instrumental goals. We maintain positive relationships through relational goals. We also strategically present ourselves in order to be perceived in particular ways. As our goals are met and our relationships build, they become little worlds we inhabit with our relational partners, complete with their own relationship cultures.

Cultural Aspects of Interpersonal Communication

Aside from functional aspects of interpersonal communication, communicating in relationships also helps establish relationship cultures. Just as large groups of people create cultures through shared symbols (language), values, and rituals, people in relationships also create cultures at a smaller level. Relationship cultures are the climates established through interpersonal communication that are unique to the relational partners but based on larger cultural and social norms. We also enter into new relationships with expectations based on the schemata we have developed in previous relationships and learned from our larger society and culture. Think of relationship schemata as blueprints or plans that show the inner workings of a relationship. Just like a schematic or diagram for assembling a new computer desk helps you put it together, relationship schemata guide us in how we believe our interpersonal relationships should work and how to create them. So from our life experiences in our larger cultures, we bring building blocks, or expectations, into our relationships, which fundamentally connect our relationships to the outside world. Brant R. Burleson, Sandra Metts, and Michael W. Kirch, “Communication in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 252. Even though we experience our relationships as unique, they are at least partially built on preexisting cultural norms.

Some additional communicative acts that create our relational cultures include relational storytelling, personal idioms, routines and rituals, and rules and norms. Storytelling is an important part of how we create culture in larger contexts and how we create a uniting and meaningful storyline for our relationships. In fact, an anthropologist coined the term homo narrans to describe the unique storytelling capability of modern humans. Walter R. Fisher, “Narration as Human Communication Paradigm: The Case of Public Moral Argument,” Communication Monographs 51, no. 1 (1985): 1–22. We often rely on relationship storytelling to create a sense of stability in the face of change, test the compatibility of potential new relational partners, or create or maintain solidarity in established relationships. Think of how you use storytelling among your friends, family, coworkers, and other relational partners. If you recently moved to a new place for college, you probably experienced some big changes. One of the first things you started to do was reestablish a social network—remember, human beings are fundamentally social creatures. As you began to encounter new people in your classes, at your new job, or in your new housing, you most likely told some stories of your life before—about your friends, job, or teachers back home. One of the functions of this type of storytelling, early in forming interpersonal bonds, is a test to see if the people you are meeting have similar stories or can relate to your previous relationship cultures. In short, you are testing the compatibility of your schemata with the new people you encounter. Although storytelling will continue to play a part in your relational development with these new people, you may be surprised at how quickly you start telling stories with your new friends about things that have happened since you met. You may recount stories about your first trip to the dance club together, the weird geology professor you had together, or the time you all got sick from eating the cafeteria food. In short, your old stories will start to give way to new stories that you’ve created. Storytelling within relationships helps create solidarity, or a sense of belonging and closeness. This type of storytelling can be especially meaningful for relationships that don’t fall into the dominant culture. For example, research on a gay male friendship circle found that the gay men retold certain dramatic stories frequently to create a sense of belonging and to also bring in new members to the group.{Author’s name retracted as requested by work’s original creator or licensee}, “Drag Queens, Drama Queens, and Friends: Drama and Performance as a Solidarity Building Function in a Gay Male Friendship Circle,” Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research 6, no. 1 (2007): 61–84.

We also create personal idioms in our relationships. R. A. Bell and J. G. Healey, “Idiomatic Communication and Interpersonal Solidarity in Friends’ Relational Cultures,” Human Communication Research 18 (1992): 307–35. If you’ve ever studied foreign languages, you know that idiomatic expressions like “I’m under the weather today” are basically nonsense when translated. For example, the equivalent of this expression in French translates to “I’m not in my plate today.” When you think about it, it doesn’t make sense to use either expression to communicate that you’re sick, but the meaning would not be lost on English or French speakers, because they can decode their respective idiom. This is also true of idioms we create in our interpersonal relationships. Just as idioms are unique to individual cultures and languages, personal idioms are unique to certain relationships, and they create a sense of belonging due to the inside meaning shared by the relational partners. In romantic relationships, for example, it is common for individuals to create nicknames for each other that may not directly translate for someone who overhears them. You and your partner may find that calling each other “booger” is sweet, while others may think it’s gross. Researchers have found that personal idioms are commonly used in the following categories: activities, labels for others, requests, and sexual references. Robert A. Bell and Jonathan G. Healey, “Idiomatic Communication and Interpersonal Solidarity in Friends’ Relational Cultures,” Human Communication Research 18, no. 3 (1992): 312–13. The recent cultural phenomenon Jersey Shore on MTV has given us plenty of examples of personal idioms created by the friends on the show. GTL is an activity idiom that stands for “gym, tan, laundry”—a common routine for the cast of the show. There are many examples of idioms labeling others, including grenade for an unattractive female, gorilla juice head for a very muscular man, and backpack for a clingy boyfriend/girlfriend or a clingy person at a club. There are also many idioms for sexual references, such as smush, meaning to hook up / have sex, and smush room, which is the room set aside for these activities. Anthony Benigno, “Jersey Shore Glossary: This Dictionary of Terms Will Get You (Fist) Pumped for Season Two,” N.Y. Daily News, July 28, 2010, http://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/tv-movies/jersey-shore-glossary-dictionary-terms-fist-pumped-season-article-1.200467. Idioms help create cohesiveness, or solidarity in relationships, because they are shared cues between cultural insiders. They also communicate the uniqueness of the relationship and create boundaries, since meaning is only shared within the relationship.

Routines and rituals help form relational cultures through their natural development in repeated or habitual interaction. Brant R. Burleson, Sandra Metts, and Michael W. Kirch, “Communication in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 254–55. While “routine” may connote boring in some situations, relationship routines are communicative acts that create a sense of predictability in a relationship that is comforting. Some communicative routines may develop around occasions or conversational topics.

For example, it is common for long-distance friends or relatives to schedule a recurring phone conversation or for couples to review the day’s events over dinner. When I studied abroad in Sweden, my parents and I talked on the phone at the same time every Sunday, which established a comfortable routine for us. Other routines develop around entire conversational episodes. For example, two best friends recounting their favorite spring-break story may seamlessly switch from one speaker to the other, finish each other’s sentences, speak in unison, or gesture simultaneously because they have told the story so many times. Relationship rituals take on more symbolic meaning than do relationship routines and may be variations on widely recognized events—such as birthdays, anniversaries, Passover, Christmas, or Thanksgiving—or highly individualized and original. Relational partners may personalize their traditions by eating mussels and playing Yahtzee on Christmas Eve or going hiking on their anniversary. Other rituals may be more unique to the relationship, such as celebrating a dog’s birthday or going to opening day at the amusement park. The following highly idiosyncratic ritual was reported by a participant in a research study:

I would check my husband’s belly button for fuzz on a daily basis at bedtime. It originated when I noticed some blanket fuzz in his belly button one day and thought it was funny…We both found it funny and teased often about the fuzz. If there wasn’t any fuzz for a few days my husband would put some in his belly button for me to find. It’s been happening for about 10 years now. Carol J. S. Bruess and Judy C. Pearson, “Interpersonal Rituals in Marriage and Adult Friendship,” Communication Monographs 64, no. 1 (1997): 35.

Whether the routines and rituals involve phone calls, eating certain foods, or digging for belly button fuzz, they all serve important roles in building relational cultures. However, as with storytelling, rituals and routines can be negative. For example, verbal and nonverbal patterns to berate or belittle your relational partner will not have healthy effects on a relational culture. Additionally, visiting your in-laws during the holidays loses its symbolic value when you dislike them and comply with the ritual because you feel like you have to. In this case, the ritual doesn’t enrich the relational culture, but it may reinforce norms or rules that have been created in the relationship.

Relationship rules and norms help with the daily function of the relationship. They help create structure and provide boundaries for interacting in the relationship and for interacting with larger social networks. Brant R. Burleson, Sandra Metts, and Michael W. Kirch, “Communication in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 255–56. Relationship rules are explicitly communicated guidelines for what should and should not be done in certain contexts. A couple could create a rule to always confer with each other before letting their child spend the night somewhere else. If a mother lets her son sleep over at a friend’s house without consulting her partner, a more serious conflict could result. Relationship norms are similar to routines and rituals in that they develop naturally in a relationship and generally conform to or are adapted from what is expected and acceptable in the larger culture or society. For example, it may be a norm that you and your coworkers do not “talk shop” at your Friday happy-hour gathering. So when someone brings up work at the gathering, his coworkers may remind him that there’s no shop talk, and the consequences may not be that serious. In regards to topic of conversation, norms often guide expectations of what subjects are appropriate within various relationships. Do you talk to your boss about your personal finances? Do you talk to your father about your sexual activity? Do you tell your classmates about your medical history? In general, there are no rules that say you can’t discuss any of these topics with anyone you choose, but relational norms usually lead people to answer “no” to the questions above. Violating relationship norms and rules can negatively affect a relationship, but in general, rule violations can lead to more direct conflict, while norm violations can lead to awkward social interactions. Developing your interpersonal communication competence will help you assess your communication in relation to the many rules and norms you will encounter.

Key Takeaways

Getting integrated: Interpersonal communication occurs between two or more people whose lives are interdependent and mutually influence one another. These relationships occur in academic, professional, personal, and civic contexts, and improving our interpersonal communication competence can also improve our physical and psychological health, enhance our relationships, and make us more successful in our careers.

There are functional aspects of interpersonal communication.

We “get things done” in our relationships by communicating for instrumental goals such as getting someone to do something for us, requesting or presenting information, and asking for or giving support.

We maintain our relationships by communicating for relational goals such as putting your relational partner’s needs before your own, celebrating accomplishments, spending time together, and checking in.

We strategically project ourselves to be perceived in particular ways by communicating for self-presentation goals such as appearing competent or friendly.

There are cultural aspects of interpersonal communication.

We create relationship cultures based on the relationship schemata we develop through our interactions with our larger society and culture.

We engage in relationship storytelling to create a sense of stability in the face of change, to test our compatibility with potential relational partners, and to create a sense of solidarity and belonging in established relationships.

We create personal idioms such as nicknames that are unique to our particular relationship and are unfamiliar to outsiders to create cohesiveness and solidarity.

We establish relationship routines and rituals to help establish our relational culture and bring a sense of comfort and predictability to our relationships.

Exercises

Getting integrated: In what ways might interpersonal communication competence vary among academic, professional, and civic contexts? What competence skills might be more or less important in one context than in another?

Recount a time when you had a DTR talk. At what stage in the relationship was the talk? What motivated you or the other person to initiate the talk? What was the result of the talk?

Pick an important relationship and describe its relationship culture. When the relationship started, what relationship schemata guided your expectations? Describe a relationship story that you tell with this person or about this person. What personal idioms do you use? What routines and rituals do you observe? What norms and rules do you follow?

6.2 Conflict and Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

Define interpersonal conflict.

Compare and contrast the five styles of interpersonal conflict management.

Explain how perception and culture influence interpersonal conflict.

List strategies for effectively managing conflict.

Who do you have the most conflict with right now? Your answer to this question probably depends on the various contexts in your life. If you still live at home with a parent or parents, you may have daily conflicts with your family as you try to balance your autonomy, or desire for independence, with the practicalities of living under your family’s roof. If you’ve recently moved away to go to college, you may be negotiating roommate conflicts as you adjust to living with someone you may not know at all. You probably also have experiences managing conflict in romantic relationships and in the workplace. So think back and ask yourself, “How well do I handle conflict?” As with all areas of communication, we can improve if we have the background knowledge to identify relevant communication phenomena and the motivation to reflect on and enhance our communication skills.

Interpersonal conflict occurs in interactions where there are real or perceived incompatible goals, scarce resources, or opposing viewpoints. Interpersonal conflict may be expressed verbally or nonverbally along a continuum ranging from a nearly imperceptible cold shoulder to a very obvious blowout. Interpersonal conflict is, however, distinct from interpersonal violence, which goes beyond communication to include abuse. Domestic violence is a serious issue and is discussed in the section “The Dark Side of Relationships.”

Conflict is an inevitable part of close relationships and can take a negative emotional toll. It takes effort to ignore someone or be passive aggressive, and the anger or guilt we may feel after blowing up at someone are valid negative feelings. However, conflict isn’t always negative or unproductive. In fact, numerous research studies have shown that quantity of conflict in a relationship is not as important as how the conflict is handled. Howard J. Markman, Mari Jo Renick, Frank J. Floyd, Scott M. Stanley, and Mari Clements, “Preventing Marital Distress through Communication and Conflict Management Training: A 4- and 5-Year Follow-Up,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61, no. 1 (1993): 70–77. Additionally, when conflict is well managed, it has the potential to lead to more rewarding and satisfactory relationships. Daniel J. Canary and Susan J. Messman, “Relationship Conflict,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 261–70.

Improving your competence in dealing with conflict can yield positive effects in the real world. Since conflict is present in our personal and professional lives, the ability to manage conflict and negotiate desirable outcomes can help us be more successful at both. Whether you and your partner are trying to decide what brand of flat-screen television to buy or discussing the upcoming political election with your mother, the potential for conflict is present. In professional settings, the ability to engage in conflict management, sometimes called conflict resolution, is a necessary and valued skill. However, many professionals do not receive training in conflict management even though they are expected to do it as part of their job. Steve Gates, “Time to Take Negotiation Seriously,” Industrial and Commercial Training 38 (2006): 238–41. A lack of training and a lack of competence could be a recipe for disaster, which is illustrated in an episode of The Office titled “Conflict Resolution.” In the episode, Toby, the human-resources officer, encourages office employees to submit anonymous complaints about their coworkers. Although Toby doesn’t attempt to resolve the conflicts, the employees feel like they are being heard. When Michael, the manager, finds out there is unresolved conflict, he makes the anonymous complaints public in an attempt to encourage resolution, which backfires, creating more conflict within the office. As usual, Michael doesn’t demonstrate communication competence; however, there are career paths for people who do have an interest in or talent for conflict management. In fact, being a mediator was named one of the best careers for 2011 by U.S. News and World Report. “Mediator on Best Career List for 2011,” UNCG Program in Conflict and Peace Studies Blog, accessed November 5, 2012, http://conresuncg.blogspot.com/2011/04/mediator-on-best-career-list-for-2011.html. Many colleges and universities now offer undergraduate degrees, graduate degrees, or certificates in conflict resolution, such as this one at the University of North Carolina Greensboro: http://conflictstudies.uncg.edu/site. Being able to manage conflict situations can make life more pleasant rather than letting a situation stagnate or escalate. The negative effects of poorly handled conflict could range from an awkward last few weeks of the semester with a college roommate to violence or divorce. However, there is no absolute right or wrong way to handle a conflict. Remember that being a competent communicator doesn’t mean that you follow a set of absolute rules. Rather, a competent communicator assesses multiple contexts and applies or adapts communication tools and skills to fit the dynamic situation.

Conflict Management Styles

Would you describe yourself as someone who prefers to avoid conflict? Do you like to get your way? Are you good at working with someone to reach a solution that is mutually beneficial? Odds are that you have been in situations where you could answer yes to each of these questions, which underscores the important role context plays in conflict and conflict management styles in particular. The way we view and deal with conflict is learned and contextual. Is the way you handle conflicts similar to the way your parents handle conflict? If you’re of a certain age, you are likely predisposed to answer this question with a certain “No!” It wasn’t until my late twenties and early thirties that I began to see how similar I am to my parents, even though I, like many, spent years trying to distinguish myself from them. Research does show that there is intergenerational transmission of traits related to conflict management. As children, we test out different conflict resolution styles we observe in our families with our parents and siblings. Later, as we enter adolescence and begin developing platonic and romantic relationships outside the family, we begin testing what we’ve learned from our parents in other settings. If a child has observed and used negative conflict management styles with siblings or parents, he or she is likely to exhibit those behaviors with non–family members. Maria Reese-Weber and Suzanne Bartle-Haring, “Conflict Resolution Styles in Family Subsystems and Adolescent Romantic Relationships,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 27, no. 6 (1998): 735–52.

There has been much research done on different types of conflict management styles, which are communication strategies that attempt to avoid, address, or resolve a conflict. Keep in mind that we don’t always consciously choose a style. We may instead be caught up in emotion and become reactionary. The strategies for more effectively managing conflict that will be discussed later may allow you to slow down the reaction process, become more aware of it, and intervene in the process to improve your communication. A powerful tool to mitigate conflict is information exchange. Asking for more information before you react to a conflict-triggering event is a good way to add a buffer between the trigger and your reaction. Another key element is whether or not a communicator is oriented toward self-centered or other-centered goals. For example, if your goal is to “win” or make the other person “lose,” you show a high concern for self and a low concern for other. If your goal is to facilitate a “win/win” resolution or outcome, you show a high concern for self and other. In general, strategies that facilitate information exchange and include concern for mutual goals will be more successful at managing conflict. Allan L. Sillars, “Attributions and Communication in Roommate Conflicts,” Communication Monographs 47, no. 3 (1980): 180–200.

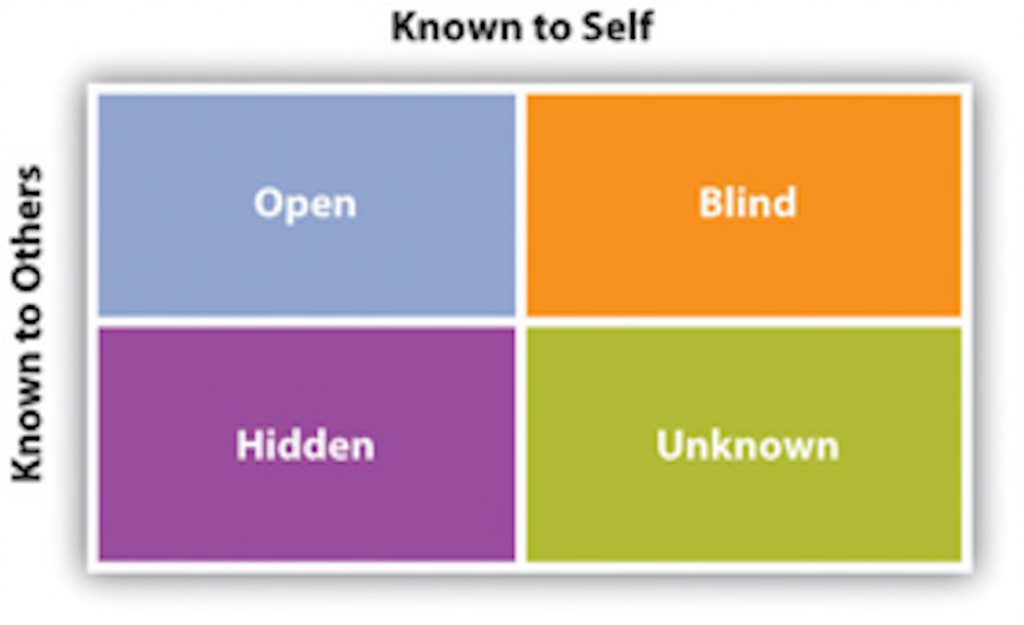

The five strategies for managing conflict we will discuss are competing, avoiding, accommodating, compromising, and collaborating. Each of these conflict styles accounts for the concern we place on self versus other (see Figure 6.1 “Five Styles of Interpersonal Conflict Management”).

Figure 6.1 Five Styles of Interpersonal Conflict Management

Source: Adapted from M. Afzalur Rahim, “A Measure of Styles of Handling Interpersonal Conflict,” Academy of Management Journal 26, no. 2 (1983): 368–76.

In order to better understand the elements of the five styles of conflict management, we will apply each to the follow scenario. Rosa and D’Shaun have been partners for seventeen years. Rosa is growing frustrated because D’Shaun continues to give money to their teenage daughter, Casey, even though they decided to keep the teen on a fixed allowance to try to teach her more responsibility. While conflicts regarding money and child rearing are very common, we will see the numerous ways that Rosa and D’Shaun could address this problem.

Competing

The competing style indicates a high concern for self and a low concern for other. When we compete, we are striving to “win” the conflict, potentially at the expense or “loss” of the other person. One way we may gauge our win is by being granted or taking concessions from the other person. For example, if D’Shaun gives Casey extra money behind Rosa’s back, he is taking an indirect competitive route resulting in a “win” for him because he got his way. The competing style also involves the use of power, which can be noncoercive or coercive. Allan L. Sillars, “Attributions and Communication in Roommate Conflicts,” Communication Monographs 47, no. 3 (1980): 180–200. Noncoercive strategies include requesting and persuading. When requesting, we suggest the conflict partner change a behavior. Requesting doesn’t require a high level of information exchange. When we persuade, however, we give our conflict partner reasons to support our request or suggestion, meaning there is more information exchange, which may make persuading more effective than requesting. Rosa could try to persuade D’Shaun to stop giving Casey extra allowance money by bringing up their fixed budget or reminding him that they are saving for a summer vacation. Coercive strategies violate standard guidelines for ethical communication and may include aggressive communication directed at rousing your partner’s emotions through insults, profanity, and yelling, or through threats of punishment if you do not get your way. If Rosa is the primary income earner in the family, she could use that power to threaten to take D’Shaun’s ATM card away if he continues giving Casey money. In all these scenarios, the “win” that could result is only short term and can lead to conflict escalation. Interpersonal conflict is rarely isolated, meaning there can be ripple effects that connect the current conflict to previous and future conflicts. D’Shaun’s behind-the-scenes money giving or Rosa’s confiscation of the ATM card could lead to built-up negative emotions that could further test their relationship.

Competing has been linked to aggression, although the two are not always paired. If assertiveness does not work, there is a chance it could escalate to hostility. There is a pattern of verbal escalation: requests, demands, complaints, angry statements, threats, harassment, and verbal abuse. Kristen Linnea Johnson and Michael E. Roloff, “Correlates of the Perceived Resolvability and Relational Consequences of Serial Arguing in Dating Relationships: Argumentative Features and the Use of Coping Strategies,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 17, no. 4–5 (2000): 677–78. Aggressive communication can become patterned, which can create a volatile and hostile environment. The reality television show The Bad Girls Club is a prime example of a chronically hostile and aggressive environment. If you do a Google video search for clips from the show, you will see yelling, screaming, verbal threats, and some examples of physical violence. The producers of the show choose houseguests who have histories of aggression, and when the “bad girls” are placed in a house together, they fall into typical patterns, which creates dramatic television moments. Obviously, living in this type of volatile environment would create stressors in any relationship, so it’s important to monitor the use of competing as a conflict resolution strategy to ensure that it does not lapse into aggression.

The competing style of conflict management is not the same thing as having a competitive personality. Competition in relationships isn’t always negative, and people who enjoy engaging in competition may not always do so at the expense of another person’s goals. In fact, research has shown that some couples engage in competitive shared activities like sports or games to maintain and enrich their relationship. Kathryn Dindia and Leslie A. Baxter, “Strategies for Maintaining and Repairing Marital Relationships,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 4, no. 2 (1987): 143–58. And although we may think that competitiveness is gendered, research has often shown that women are just as competitive as men. Susan J. Messman and Rebecca L. Mikesell, “Competition and Interpersonal Conflict in Dating Relationships,” Communication Reports 13, no. 1 (2000): 32.

Avoiding

The avoiding style of conflict management often indicates a low concern for self and a low concern for other, and no direct communication about the conflict takes place. However, as we will discuss later, in some cultures that emphasize group harmony over individual interests, and even in some situations in the United States, avoiding a conflict can indicate a high level of concern for the other. In general, avoiding doesn’t mean that there is no communication about the conflict. Remember, you cannot not communicate. Even when we try to avoid conflict, we may intentionally or unintentionally give our feelings away through our verbal and nonverbal communication. Rosa’s sarcastic tone as she tells D’Shaun that he’s “Soooo good with money!” and his subsequent eye roll both bring the conflict to the surface without specifically addressing it. The avoiding style is either passive or indirect, meaning there is little information exchange, which may make this strategy less effective than others. We may decide to avoid conflict for many different reasons, some of which are better than others. If you view the conflict as having little importance to you, it may be better to ignore it. If the person you’re having conflict with will only be working in your office for a week, you may perceive a conflict to be temporary and choose to avoid it and hope that it will solve itself. If you are not emotionally invested in the conflict, you may be able to reframe your perspective and see the situation in a different way, therefore resolving the issue. In all these cases, avoiding doesn’t really require an investment of time, emotion, or communication skill, so there is not much at stake to lose.

Avoidance is not always an easy conflict management choice, because sometimes the person we have conflict with isn’t a temp in our office or a weekend houseguest. While it may be easy to tolerate a problem when you’re not personally invested in it or view it as temporary, when faced with a situation like Rosa and D’Shaun’s, avoidance would just make the problem worse. For example, avoidance could first manifest as changing the subject, then progress from avoiding the issue to avoiding the person altogether, to even ending the relationship.

Indirect strategies of hinting and joking also fall under the avoiding style. While these indirect avoidance strategies may lead to a buildup of frustration or even anger, they allow us to vent a little of our built-up steam and may make a conflict situation more bearable. When we hint, we drop clues that we hope our partner will find and piece together to see the problem and hopefully change, thereby solving the problem without any direct communication. In almost all the cases of hinting that I have experienced or heard about, the person dropping the hints overestimates their partner’s detective abilities. For example, when Rosa leaves the bank statement on the kitchen table in hopes that D’Shaun will realize how much extra money he is giving Casey, D’Shaun may simply ignore it or even get irritated with Rosa for not putting the statement with all the other mail. We also overestimate our partner’s ability to decode the jokes we make about a conflict situation. It is more likely that the receiver of the jokes will think you’re genuinely trying to be funny or feel provoked or insulted than realize the conflict situation that you are referencing. So more frustration may develop when the hints and jokes are not decoded, which often leads to a more extreme form of hinting/joking: passive-aggressive behavior.

Passive-aggressive behavior is a way of dealing with conflict in which one person indirectly communicates their negative thoughts or feelings through nonverbal behaviors, such as not completing a task. For example, Rosa may wait a few days to deposit money into the bank so D’Shaun can’t withdraw it to give to Casey, or D’Shaun may cancel plans for a romantic dinner because he feels like Rosa is questioning his responsibility with money. Although passive-aggressive behavior can feel rewarding in the moment, it is one of the most unproductive ways to deal with conflict. These behaviors may create additional conflicts and may lead to a cycle of passive-aggressiveness in which the other partner begins to exhibit these behaviors as well, while never actually addressing the conflict that originated the behavior. In most avoidance situations, both parties lose. However, as noted above, avoidance can be the most appropriate strategy in some situations—for example, when the conflict is temporary, when the stakes are low or there is little personal investment, or when there is the potential for violence or retaliation.

Accommodating

The accommodating conflict management style indicates a low concern for self and a high concern for other and is often viewed as passive or submissive, in that someone complies with or obliges another without providing personal input. The context for and motivation behind accommodating play an important role in whether or not it is an appropriate strategy. Generally, we accommodate because we are being generous, we are obeying, or we are yielding. Lionel Bobot, “Conflict Management in Buyer-Seller Relationships,” Conflict Resolution Quarterly 27, no. 3 (2010): 296. If we are being generous, we accommodate because we genuinely want to; if we are obeying, we don’t have a choice but to accommodate (perhaps due to the potential for negative consequences or punishment); and if we yield, we may have our own views or goals but give up on them due to fatigue, time constraints, or because a better solution has been offered. Accommodating can be appropriate when there is little chance that our own goals can be achieved, when we don’t have much to lose by accommodating, when we feel we are wrong, or when advocating for our own needs could negatively affect the relationship. Myra Warren Isenhart and Michael Spangle, Collaborative Approaches to Resolving Conflict (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 26. The occasional accommodation can be useful in maintaining a relationship—remember earlier we discussed putting another’s needs before your own as a way to achieve relational goals. For example, Rosa may say, “It’s OK that you gave Casey some extra money; she did have to spend more on gas this week since the prices went up.” However, being a team player can slip into being a pushover, which people generally do not appreciate. If Rosa keeps telling D’Shaun, “It’s OK this time,” they may find themselves short on spending money at the end of the month. At that point, Rosa and D’Shaun’s conflict may escalate as they question each other’s motives, or the conflict may spread if they direct their frustration at Casey and blame it on her irresponsibility.

Research has shown that the accommodating style is more likely to occur when there are time restraints and less likely to occur when someone does not want to appear weak. Deborah A. Cai and Edward L. Fink, “Conflict Style Differences between Individualists and Collectivists,” Communication Monographs69, no. 1 (2002): 67–87. If you’re standing outside the movie theatre and two movies are starting, you may say, “Let’s just have it your way,” so you don’t miss the beginning. If you’re a new manager at an electronics store and an employee wants to take Sunday off to watch a football game, you may say no to set an example for the other employees. As with avoiding, there are certain cultural influences we will discuss later that make accommodating a more effective strategy.

Compromising

The compromising style shows a moderate concern for self and other and may indicate that there is a low investment in the conflict and/or the relationship. Even though we often hear that the best way to handle a conflict is to compromise, the compromising style isn’t a win/win solution; it is a partial win/lose. In essence, when we compromise, we give up some or most of what we want. It’s true that the conflict gets resolved temporarily, but lingering thoughts of what you gave up could lead to a future conflict. Compromising may be a good strategy when there are time limitations or when prolonging a conflict may lead to relationship deterioration. Compromise may also be good when both parties have equal power or when other resolution strategies have not worked. Gerrard Macintosh and Charles Stevens, “Personality, Motives, and Conflict Strategies in Everyday Service Encounters,” International Journal of Conflict Management 19, no. 2 (2008): 115.

A negative of compromising is that it may be used as an easy way out of a conflict. The compromising style is most effective when both parties find the solution agreeable. Rosa and D’Shaun could decide that Casey’s allowance does need to be increased and could each give ten more dollars a week by committing to taking their lunch to work twice a week instead of eating out. They are both giving up something, and if neither of them have a problem with taking their lunch to work, then the compromise was equitable. If the couple agrees that the twenty extra dollars a week should come out of D’Shaun’s golf budget, the compromise isn’t as equitable, and D’Shaun, although he agreed to the compromise, may end up with feelings of resentment. Wouldn’t it be better to both win?

Collaborating

The collaborating style involves a high degree of concern for self and other and usually indicates investment in the conflict situation and the relationship. Although the collaborating style takes the most work in terms of communication competence, it ultimately leads to a win/win situation in which neither party has to make concessions because a mutually beneficial solution is discovered or created. The obvious advantage is that both parties are satisfied, which could lead to positive problem solving in the future and strengthen the overall relationship. For example, Rosa and D’Shaun may agree that Casey’s allowance needs to be increased and may decide to give her twenty more dollars a week in exchange for her babysitting her little brother one night a week. In this case, they didn’t make the conflict personal but focused on the situation and came up with a solution that may end up saving them money. The disadvantage is that this style is often time consuming, and only one person may be willing to use this approach while the other person is eager to compete to meet their goals or willing to accommodate.

Here are some tips for collaborating and achieving a win/win outcome: Owen Hargie, Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (London: Routledge, 2011), 406–7, 430.

- Do not view the conflict as a contest you are trying to win.

- Remain flexible and realize there are solutions yet to be discovered.

- Distinguish the people from the problem (don’t make it personal).

- Determine what the underlying needs are that are driving the other person’s demands (needs can still be met through different demands).

- Identify areas of common ground or shared interests that you can work from to develop solutions.

- Ask questions to allow them to clarify and to help you understand their perspective.

- Listen carefully and provide verbal and nonverbal feedback.

“Getting Competent”

Handling Roommate Conflicts

Whether you have a roommate by choice, by necessity, or through the random selection process of your school’s housing office, it’s important to be able to get along with the person who shares your living space. While having a roommate offers many benefits such as making a new friend, having someone to experience a new situation like college life with, and having someone to split the cost on your own with, there are also challenges. Some common roommate conflicts involve neatness, noise, having guests, sharing possessions, value conflicts, money conflicts, and personality conflicts. Ball State University, “Roommate Conflicts,” accessed June 16, 2001, http://cms.bsu.edu/campuslife/housing/roomsignup/roommates. Read the following scenarios and answer the following questions for each one:

- Which conflict management style, from the five discussed, would you use in this situation?

- What are the potential strengths of using this style?

- What are the potential weaknesses of using this style?

Scenario 1: Neatness. Your college dorm has bunk beds, and your roommate takes a lot of time making his bed (the bottom bunk) each morning. He has told you that he doesn’t want anyone sitting on or sleeping in his bed when he is not in the room. While he is away for the weekend, your friend comes to visit and sits on the bottom bunk bed. You tell him what your roommate said, and you try to fix the bed back before he returns to the dorm. When he returns, he notices that his bed has been disturbed and he confronts you about it.

Scenario 2: Noise and having guests. Your roommate has a job waiting tables and gets home around midnight on Thursday nights. She often brings a couple friends from work home with her. They watch television, listen to music, or play video games and talk and laugh. You have an 8 a.m. class on Friday mornings and are usually asleep when she returns. Last Friday, you talked to her and asked her to keep it down in the future. Tonight, their noise has woken you up and you can’t get back to sleep.

Scenario 3: Sharing possessions. When you go out to eat, you often bring back leftovers to have for lunch the next day during your short break between classes. You didn’t have time to eat breakfast, and you’re really excited about having your leftover pizza for lunch until you get home and see your roommate sitting on the couch eating the last slice.

Scenario 4: Money conflicts. Your roommate got mono and missed two weeks of work last month. Since he has a steady job and you have some savings, you cover his portion of the rent and agree that he will pay your portion next month. The next month comes around and he informs you that he only has enough to pay his half.

Scenario 5: Value and personality conflicts. You like to go out to clubs and parties and have friends over, but your roommate is much more of an introvert. You’ve tried to get her to come out with you or join the party at your place, but she’d rather study. One day she tells you that she wants to break the lease so she can move out early to live with one of her friends. You both signed the lease, so you have to agree or she can’t do it. If you break the lease, you automatically lose your portion of the security deposit.

Culture and Conflict

Culture is an important context to consider when studying conflict, and recent research has called into question some of the assumptions of the five conflict management styles discussed so far, which were formulated with a Western bias. John Oetzel, Adolfo J. Garcia, and Stella Ting-Toomey, “An Analysis of the Relationships among Face Concerns and Facework Behaviors in Perceived Conflict Situations: A Four-Culture Investigation,” International Journal of Conflict Management 19, no. 4 (2008): 382–403. For example, while the avoiding style of conflict has been cast as negative, with a low concern for self and other or as a lose/lose outcome, this research found that participants in the United States, Germany, China, and Japan all viewed avoiding strategies as demonstrating a concern for the other. While there are some generalizations we can make about culture and conflict, it is better to look at more specific patterns of how interpersonal communication and conflict management are related. We can better understand some of the cultural differences in conflict management by further examining the concept of face.

What does it mean to “save face?” This saying generally refers to preventing embarrassment or preserving our reputation or image, which is similar to the concept of face in interpersonal and intercultural communication. Our face is the projected self we desire to put into the world, and facework refers to the communicative strategies we employ to project, maintain, or repair our face or maintain, repair, or challenge another’s face. Face negotiation theory argues that people in all cultures negotiate face through communication encounters, and that cultural factors influence how we engage in facework, especially in conflict situations. John G. Oetzel and Stella Ting-Toomey, “Face Concerns in Interpersonal Conflict: A Cross-Cultural Empirical Test of the Face Negotiation Theory,” Communication Research 30, no. 6 (2003): 600. These cultural factors influence whether we are more concerned with self-face or other-face and what types of conflict management strategies we may use. One key cultural influence on face negotiation is the distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultures.

The distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultures is an important dimension across which all cultures vary. Individualistic cultures like the United States and most of Europe emphasize individual identity over group identity and encourage competition and self-reliance. Collectivistic cultures like Taiwan, Colombia, China, Japan, Vietnam, and Peru value in-group identity over individual identity and value conformity to social norms of the in-group. Mararet U. Dsilva and Lisa O. Whyte, “Cultural Differences in Conflict Styles: Vietnamese Refugees and Established Residents,” Howard Journal of Communication 9 (1998): 59. However, within the larger cultures, individuals will vary in the degree to which they view themselves as part of a group or as a separate individual, which is called self-construal. Independent self-construal indicates a perception of the self as an individual with unique feelings, thoughts, and motivations. Interdependent self-construal indicates a perception of the self as interrelated with others. John G. Oetzel and Stella Ting-Toomey, “Face Concerns in Interpersonal Conflict: A Cross-Cultural Empirical Test of the Face Negotiation Theory,” Communication Research 30, no. 6 (2003): 603. Not surprisingly, people from individualistic cultures are more likely to have higher levels of independent self-construal, and people from collectivistic cultures are more likely to have higher levels of interdependent self-construal. Self-construal and individualistic or collectivistic cultural orientations affect how people engage in facework and the conflict management styles they employ.

Self-construal alone does not have a direct effect on conflict style, but it does affect face concerns, with independent self-construal favoring self-face concerns and interdependent self-construal favoring other-face concerns. There are specific facework strategies for different conflict management styles, and these strategies correspond to self-face concerns or other-face concerns.

- Accommodating. Giving in (self-face concern).

- Avoiding. Pretending conflict does not exist (other-face concern).

- Competing. Defending your position, persuading (self-face concern).

- Collaborating. Apologizing, having a private discussion, remaining calm (other-face concern). John Oetzel, Adolfo J. Garcia, and Stella Ting-Toomey, “An Analysis of the Relationships among Face Concerns and Facework Behaviors in Perceived Conflict Situations: A Four-Culture Investigation,” International Journal of Conflict Management 19, no. 4 (2008): 385.

Research done on college students in Germany, Japan, China, and the United States found that those with independent self-construal were more likely to engage in competing, and those with interdependent self-construal were more likely to engage in avoiding or collaborating. John G. Oetzel and Stella Ting-Toomey, “Face Concerns in Interpersonal Conflict: A Cross-Cultural Empirical Test of the Face Negotiation Theory,” Communication Research 30, no. 6 (2003): 599–624. And in general, this research found that members of collectivistic cultures were more likely to use the avoiding style of conflict management and less likely to use the integrating or competing styles of conflict management than were members of individualistic cultures. The following examples bring together facework strategies, cultural orientations, and conflict management style: Someone from an individualistic culture may be more likely to engage in competing as a conflict management strategy if they are directly confronted, which may be an attempt to defend their reputation (self-face concern). Someone in a collectivistic culture may be more likely to engage in avoiding or accommodating in order not to embarrass or anger the person confronting them (other-face concern) or out of concern that their reaction could reflect negatively on their family or cultural group (other-face concern). While these distinctions are useful for categorizing large-scale cultural patterns, it is important not to essentialize or arbitrarily group countries together, because there are measurable differences within cultures. For example, expressing one’s emotions was seen as demonstrating a low concern for other-face in Japan, but this was not so in China, which shows there is variety between similarly collectivistic cultures. Culture always adds layers of complexity to any communication phenomenon, but experiencing and learning from other cultures also enriches our lives and makes us more competent communicators.

Handling Conflict Better

Conflict is inevitable and it is not inherently negative. A key part of developing interpersonal communication competence involves being able to effectively manage the conflict you will encounter in all your relationships. One key part of handling conflict better is to notice patterns of conflict in specific relationships and to generally have an idea of what causes you to react negatively and what your reactions usually are.

Identifying Conflict Patterns

Much of the research on conflict patterns has been done on couples in romantic relationships, but the concepts and findings are applicable to other relationships. Four common triggers for conflict are criticism, demand, cumulative annoyance, and rejection. Andrew Christensen and Neil S. Jacobson, Reconcilable Differences (New York: Guilford Press, 2000), 17–20. We all know from experience that criticism, or comments that evaluate another person’s personality, behavior, appearance, or life choices, may lead to conflict. Comments do not have to be meant as criticism to be perceived as such. If Gary comes home from college for the weekend and his mom says, “Looks like you put on a few pounds,” she may view this as a statement of fact based on observation. Gary, however, may take the comment personally and respond negatively back to his mom, starting a conflict that will last for the rest of his visit. A simple but useful strategy to manage the trigger of criticism is to follow the old adage “Think before you speak.” In many cases, there are alternative ways to phrase things that may be taken less personally, or we may determine that our comment doesn’t need to be spoken at all. I’ve learned that a majority of the thoughts that we have about another person’s physical appearance, whether positive or negative, do not need to be verbalized. Ask yourself, “What is my motivation for making this comment?” and “Do I have anything to lose by not making this comment?” If your underlying reasons for asking are valid, perhaps there is another way to phrase your observation. If Gary’s mom is worried about his eating habits and health, she could wait until they’re eating dinner and ask him how he likes the food choices at school and what he usually eats.

Demands also frequently trigger conflict, especially if the demand is viewed as unfair or irrelevant. It’s important to note that demands rephrased as questions may still be or be perceived as demands. Tone of voice and context are important factors here. When you were younger, you may have asked a parent, teacher, or elder for something and heard back “Ask nicely.” As with criticism, thinking before you speak and before you respond can help manage demands and minimize conflict episodes. As we discussed earlier, demands are sometimes met with withdrawal rather than a verbal response. If you are doing the demanding, remember a higher level of information exchange may make your demand clearer or more reasonable to the other person. If you are being demanded of, responding calmly and expressing your thoughts and feelings are likely more effective than withdrawing, which may escalate the conflict.

Cumulative annoyance is a building of frustration or anger that occurs over time, eventually resulting in a conflict interaction. For example, your friend shows up late to drive you to class three times in a row. You didn’t say anything the previous times, but on the third time you say, “You’re late again! If you can’t get here on time, I’ll find another way to get to class.” Cumulative annoyance can build up like a pressure cooker, and as it builds up, the intensity of the conflict also builds. Criticism and demands can also play into cumulative annoyance. We have all probably let critical or demanding comments slide, but if they continue, it becomes difficult to hold back, and most of us have a breaking point. The problem here is that all the other incidents come back to your mind as you confront the other person, which usually intensifies the conflict. You’ve likely been surprised when someone has blown up at you due to cumulative annoyance or surprised when someone you have blown up at didn’t know there was a problem building. A good strategy for managing cumulative annoyance is to monitor your level of annoyance and occasionally let some steam out of the pressure cooker by processing through your frustration with a third party or directly addressing what is bothering you with the source.

No one likes the feeling of rejection. Rejection can lead to conflict when one person’s comments or behaviors are perceived as ignoring or invalidating the other person. Vulnerability is a component of any close relationship. When we care about someone, we verbally or nonverbally communicate. We may tell our best friend that we miss them, or plan a home-cooked meal for our partner who is working late. The vulnerability that underlies these actions comes from the possibility that our relational partner will not notice or appreciate them. When someone feels exposed or rejected, they often respond with anger to mask their hurt, which ignites a conflict. Managing feelings of rejection is difficult because it is so personal, but controlling the impulse to assume that your relational partner is rejecting you, and engaging in communication rather than reflexive reaction, can help put things in perspective. If your partner doesn’t get excited about the meal you planned and cooked, it could be because he or she is physically or mentally tired after a long day. Concepts discussed in Chapter 2 “Communication and Perception” can be useful here, as perception checking, taking inventory of your attributions, and engaging in information exchange to help determine how each person is punctuating the conflict are useful ways of managing all four of the triggers discussed.

Interpersonal conflict may take the form of serial arguing, which is a repeated pattern of disagreement over an issue. Serial arguments do not necessarily indicate negative or troubled relationships, but any kind of patterned conflict is worth paying attention to. There are three patterns that occur with serial arguing: repeating, mutual hostility, and arguing with assurances. Kristen Linnea Johnson and Michael E. Roloff, “Correlates of the Perceived Resolvability and Relational Consequences of Serial Arguing in Dating Relationships: Argumentative Features and the Use of Coping Strategies,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 17, no. 4–5 (2000): 676–86. The first pattern is repeating, which means reminding the other person of your complaint (what you want them to start/stop doing). The pattern may continue if the other person repeats their response to your reminder. For example, if Marita reminds Kate that she doesn’t appreciate her sarcastic tone, and Kate responds, “I’m soooo sorry, I forgot how perfect you are,” then the reminder has failed to effect the desired change. A predictable pattern of complaint like this leads participants to view the conflict as irresolvable. The second pattern within serial arguments is mutual hostility, which occurs when the frustration of repeated conflict leads to negative emotions and increases the likelihood of verbal aggression. Again, a predictable pattern of hostility makes the conflict seem irresolvable and may lead to relationship deterioration. Whereas the first two patterns entail an increase in pressure on the participants in the conflict, the third pattern offers some relief. If people in an interpersonal conflict offer verbal assurances of their commitment to the relationship, then the problems associated with the other two patterns of serial arguing may be ameliorated. Even though the conflict may not be solved in the interaction, the verbal assurances of commitment imply that there is a willingness to work on solving the conflict in the future, which provides a sense of stability that can benefit the relationship. Although serial arguing is not inherently bad within a relationship, if the pattern becomes more of a vicious cycle, it can lead to alienation, polarization, and an overall toxic climate, and the problem may seem so irresolvable that people feel trapped and terminate the relationship. Andrew Christensen and Neil S. Jacobson, Reconcilable Differences (New York: Guilford Press, 2000), 116–17. There are some negative, but common, conflict reactions we can monitor and try to avoid, which may also help prevent serial arguing.

Two common conflict pitfalls are one-upping and mindreading. John M. Gottman, What Predicts Divorce?: The Relationship between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1994). One-upping is a quick reaction to communication from another person that escalates the conflict. If Sam comes home late from work and Nicki says, “I wish you would call when you’re going to be late” and Sam responds, “I wish you would get off my back,” the reaction has escalated the conflict. Mindreading is communication in which one person attributes something to the other using generalizations. If Sam says, “You don’t care whether I come home at all or not!” she is presuming to know Nicki’s thoughts and feelings. Nicki is likely to respond defensively, perhaps saying, “You don’t know how I’m feeling!” One-upping and mindreading are often reactions that are more reflexive than deliberate. Remember concepts like attribution and punctuation in these moments. Nicki may have received bad news and was eager to get support from Sam when she arrived home. Although Sam perceives Nicki’s comment as criticism and justifies her comments as a reaction to Nicki’s behavior, Nicki’s comment could actually be a sign of their closeness, in that Nicki appreciates Sam’s emotional support. Sam could have said, “I know, I’m sorry, I was on my cell phone for the past hour with a client who had a lot of problems to work out.” Taking a moment to respond mindfully rather than react with a knee-jerk reflex can lead to information exchange, which could deescalate the conflict.

Validating the person with whom you are in conflict can be an effective way to deescalate conflict. While avoiding or retreating may seem like the best option in the moment, one of the key negative traits found in research on married couples’ conflicts was withdrawal, which as we learned before may result in a demand-withdrawal pattern of conflict. Often validation can be as simple as demonstrating good listening skills discussed earlier in this book by making eye contact and giving verbal and nonverbal back-channel cues like saying “mmm-hmm” or nodding your head. John M. Gottman, What Predicts Divorce?: The Relationship between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1994). This doesn’t mean that you have to give up your own side in a conflict or that you agree with what the other person is saying; rather, you are hearing the other person out, which validates them and may also give you some more information about the conflict that could minimize the likelihood of a reaction rather than a response.

As with all the aspects of communication competence we have discussed so far, you cannot expect that everyone you interact with will have the same knowledge of communication that you have after reading this book. But it often only takes one person with conflict management skills to make an interaction more effective. Remember that it’s not the quantity of conflict that determines a relationship’s success; it’s how the conflict is managed, and one person’s competent response can deescalate a conflict. Now we turn to a discussion of negotiation steps and skills as a more structured way to manage conflict.

Negotiation Steps and Skills

We negotiate daily. We may negotiate with a professor to make up a missed assignment or with our friends to plan activities for the weekend. Negotiation in interpersonal conflict refers to the process of attempting to change or influence conditions within a relationship. The negotiation skills discussed next can be adapted to all types of relational contexts, from romantic partners to coworkers. The stages of negotiating are prenegotiation, opening, exploration, bargaining, and settlement. Owen Hargie, Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (London: Routledge, 2011), 408–22.

In the prenegotiation stage, you want to prepare for the encounter. If possible, let the other person know you would like to talk to them, and preview the topic, so they will also have the opportunity to prepare. While it may seem awkward to “set a date” to talk about a conflict, if the other person feels like they were blindsided, their reaction could be negative. Make your preview simple and nonthreatening by saying something like “I’ve noticed that we’ve been arguing a lot about who does what chores around the house. Can we sit down and talk tomorrow when we both get home from class?” Obviously, it won’t always be feasible to set a date if the conflict needs to be handled immediately because the consequences are immediate or if you or the other person has limited availability. In that case, you can still prepare, but make sure you allot time for the other person to digest and respond. During this stage you also want to figure out your goals for the interaction by reviewing your instrumental, relational, and self-presentation goals. Is getting something done, preserving the relationship, or presenting yourself in a certain way the most important? For example, you may highly rank the instrumental goal of having a clean house, or the relational goal of having pleasant interactions with your roommate, or the self-presentation goal of appearing nice and cooperative. Whether your roommate is your best friend from high school or a stranger the school matched you up with could determine the importance of your relational and self-presentation goals. At this point, your goal analysis may lead you away from negotiation—remember, as we discussed earlier, avoiding can be an appropriate and effective conflict management strategy. If you decide to proceed with the negotiation, you will want to determine your ideal outcome and your bottom line, or the point at which you decide to break off negotiation. It’s very important that you realize there is a range between your ideal and your bottom line and that remaining flexible is key to a successful negotiation—remember, through collaboration a new solution could be found that you didn’t think of.