Appendix B: The Writing Process and Peer Review

The Writing Process

Many students mistakenly think that the only step involved in completing a writing assignment is sitting down at computer with a blank document and writing the assignment from start to finish. While this may work for some students for smaller assignments, it is unlikely to work as you get into longer assignments that require more complex thinking. And even if the strategy of sitting down and writing from start to finish does get the assignment done, your work is likely to be lower quality than it would be if you were to engage in the writing process. Writing as a process means taking time to think carefully and critically about your ideas even before you start writing them on paper, collecting more evidence from sources, creating and revising multiple drafts of your writing, and getting advice from teachers or classmates to help you improve your writing.

Read the article below by Chris Blankenship to understand the writing process more completely. This article originally appeared in the textbook Open English @ SLCC.

You’re probably familiar with the root of the word: “cursive.” It’s the style of writing that you may have been taught in elementary school or that you’ve seen in historical documents like the Declaration of Independence or Constitution.

Invention: Coming up with ideas.

This can include thinking about what you want to accomplish with your writing, who will be reading your writing and how to adapt to them, the genre you are writing in, your position on a topic, what you know about a topic already, etc. Invention can be as formal as brainstorm activities like mind mapping and as informal as thinking about your writing task over breakfast.

Research: Finding new information.

Even if you’re not writing a research paper, you still generally have to figure out new things to complete a writing task. This can include the traditional reading of books, articles, and websites to find information to cite in a paper, but it can also include just reading up on a topic to learn more about it, interviewing an expert, looking at examples of the genre that you’re using to figure out what its characteristics are, taking careful notes on a text that you’re analyzing, or anything else that helps you to learn something important for your writing.

Drafting: Creating the text.

This is the part that we’re all familiar with: putting words down on paper, writing introductions and conclusions, and creating cohesive paragraphs and clear sentences. But, beyond the words themselves, drafting can also include shaping the medium for your writing, such as creating an e-portfolio where your writing will be displayed. Writing includes making design choices, such as formatting, font and color use, including and positioning images, and citing sources appropriately.

Revision: Literally, seeing the text again.

I’m talking about the big ideas here: looking over what you’ve created to see if you’ve accomplished your purpose, that you’ve effectively considered your audience, that your text is cohesive and coherent, and that it does the things that other texts in that genre do.

Editing: Looking at the surface level of the text.

Editing sometimes gets lumped in with revision (or replaces it entirely). I think it’s helpful to consider them as two separate ways of thinking about a text. Editing involves thinking about the clarity of word choice and sentence structure, noticing spelling and grammatical errors, making sure that source citations meet the requirements of your citation style, and other such issues. Even if editing isn’t big-concept like revision is, it’s still a very important way of thinking about a writing task.

In your previous writing experiences, you’ve probably thought about your writing in all of the ways listed above, even if you used different terms or organized the ideas differently. However, Nancy Sommers, a researcher in rhetoric and writing studies, has found[1] that student writers tend to think about the writing process in a simple, linear way that mimics speech:

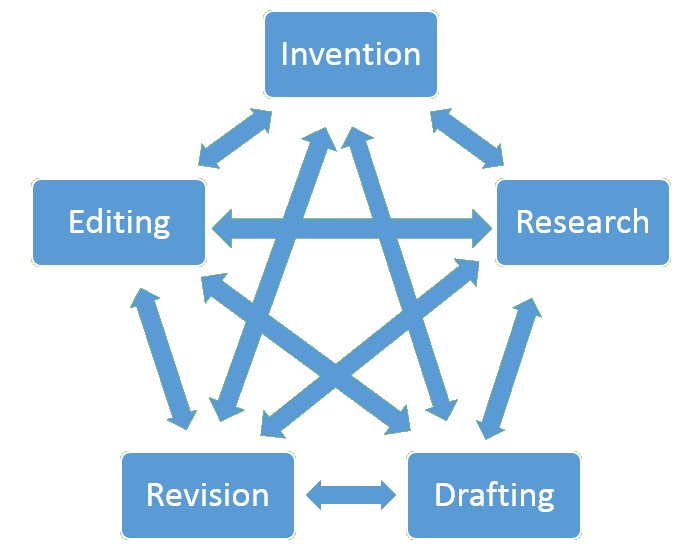

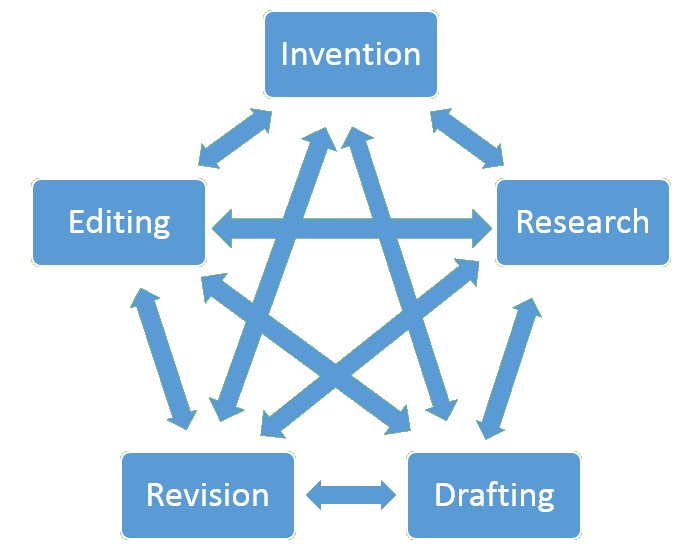

This process starts with thinking about the writing task and then moves through each part in order until, after editing, you’re finished. Even if you don’t do this every time, I’m betting that this linear process is probably familiar to you, especially if you just graduated high school.On the other hand, Sommers also researched how experienced writers approach a writing task. She found that their writing process is different from that of student writers:

Unlike student writers, professional writers, like Steven Pinker, don’t view each part of the writing process as a step to be visited just once in a particular order. Yes, they generally begin with invention and end with editing, but they view each part of the process as a valuable way of thinking that can be revisited again and again until they are confident that the product effectively meets their goals.For example, a colleague and I wrote a chapter for a book on working conditions at colleges, a topic we’re interested in.

- When we started, we had to come up with an idea for the text by talking through our experiences and deciding on a purpose for the text. [Invention]

- Although we both knew something about the topic already, we read articles and talked to experts to learn more about it. [Research]

- From that research, we decided that our original idea didn’t quite fit with the research that was out there already, so we made some changes to the big idea. [Invention]

- After that, we sat down and, over several sessions on different days, created a draft of our text. [Drafting]

- When we read through the text, we discovered that the order of the information didn’t make as much sense as we had first thought, so we moved around some paragraphs, making changes to those paragraphs to help the flow of the new order. [Revision]

- After that, we sent the rough draft to the editors of the book for feedback. When we got the chapter back, the editors commented that our topic didn’t quite fit the theme of the book, so, using that feedback, we changed the focus of the ideas. [Invention]

- Then we changed the text to reflect those new ideas. [Revision]

- We also got feedback from peer reviewers who pointed out that one part of the text was a little confusing, so we had to learn more about the ideas in that section. [Research]

- We changed the text to reflect that new understanding. [Revision and Editing]

- After the editors were satisfied with those revisions, we proofread the article and sent it off for final approval. [Editing]

In this process, we produced three distinct drafts, but each of those drafts represents several different ways that we made changes, small and large, to the text to better craft it for our audience, purpose, and context.

Although your future professors, bosses, co-workers, clients, and patients may only see the final product, mastering a complex, recursive writing process will help you to create effective texts for any situation you encounter.

- “Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers” in College Composition and Communication 31.4, 378–88 ↵

Blankenship, Chris. “Writing is Recursive.” Open English @ SLCC, 1 August, 2016, https://slcc.pressbooks.pub/openenglishatslcc/ (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License)

Peer Review

An important part of the writing process is peer review. To understand the meaning of this phrase, we can break it down into its parts. A peer is someone, like a classmate or coworker, who is at the same level as you. To “review” a text means to look it over and give suggestions to improve it so that it more clearly communicates its message to the desired audience. All levels of writers, including professional authors, use peer review to get feedback on their work and improve it.

Here is a video by writing professors at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to help you better understand the purpose of peer review for students as well as for professional researchers and scholars:

In the article below, which originally appeared in the textbook Open English @ SLCC, Jim Beatty gives some tips for successful peer review:

“Peer Review” by Jim Beatty

Peer review is a daunting prospect for many students. It can be nerve-wracking to let other people see a draft that is far from perfect. It can also be uncomfortable to critique drafts written by people you hardly know. Peer review is essential for effective public writing, however. Professors often publish in “peer-reviewed” journals, which means their drafts are sent to several experts around the world. The professor/author must then address these people’s concerns before the journal will publish the article. This process is done because, overall, the best ideas come out of conversations with other people about your writing. You should always be supportive of your peers, but you should also not pull any punches regarding things you think could really hurt their grade or the efficacy of their paper.

How to Give Feedback

The least helpful thing you can do when peer reviewing is correct grammar and typos. While these issues are important, they are commonly the least important thing English professors consider when grading. Poor grammar usually only greatly impacts your grade if it gets in the way of clarity (if the professor cannot decode what you are trying to say) or your authority (it would affect how much readers would trust you as a writer). And, with a careful editing process, a writer can catch these errors on their own. If they are convinced they have a good thesis statement and they don’t, however, then you can help them by identifying that.

Your professor may give you specific things to evaluate during peer review. If so, those criteria are your clue to what your professor values in the paper. If your professor doesn’t give you things to evaluate, make sure to have the assignment sheet in front of you when peer reviewing. If your professor provides a rubric or grading criteria, focus on those issues when giving advice to your peers. Again, don’t just look for things to “fix.” Pose questions to your classmate; let them know where they need to give you more to clarify and convince you.

How to Receive Feedback

Resist the powerful urge to get defensive over your writing. Try your best not to respond until your reviewer is finished giving and explaining their feedback. Keep in mind that your peers do not have all the information about your paper that you do. If they misunderstand something, take it as an opportunity to be clearer in your writing rather than simply blaming them for not getting it. Once you give a paper to another person, you cannot provide additional commentary or explanations. They can only evaluate what’s on the page.

Perhaps the biggest challenge in peer review is deciding what advice to use and what to ignore. When in doubt, always ask your professor. They know how they will grade, so they can give you a more definitive answer than anyone else. This holds true for the advice you get from a writing tutor too.

Make Peer Review Part of Your Life

Don’t think of peer review as an isolated activity you do because it is required in class. Make friends in the class that can help you outside of it. Call on people outside the class whom you trust to give you feedback, including writing tutors. Integrate peer review into every step of your writing process, not just when you have a complete draft. Classmates, writing tutors, and your friends can be an invaluable resource as you brainstorm your ideas. Conversations with them can give you a safe, informal opportunity to work things out before you stare at a blank screen wondering what to write. A writing tutor can help you talk out your ideas and maybe produce an outline by the end of your appointment. A friend can offer another perspective or additional information of which you are initially unaware. Again, you can get the most direct advice by visiting your professor during office hours to go over ideas and drafts. Take advantage of all the formal and informal resources surrounding you at SLCC to help you succeed.

Conclusion

Far from being scary or annoying, peer review is one of the most powerful tools at your disposal in the life-long process of becoming a more effective public writer. No good writing exists in isolation. The best writing comes out of a communal effort.

Beatty, Jim. “Peer Review.” Open English @ SLCC, 1 August, 2016, https://slcc.pressbooks.pub/openenglishatslcc/ (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License)

Reflecting on Your Writing Process

After you have completed a writing assignment, reflect on the process that you used, and think about how that process was similar to or different from your typical writing process. You can discuss these questions with your classmates:

1. What do the various stages of the writing process (invention, research, drafting, revising, editing) typically look like for you?

2. Do you usually follow a linear process, like a typical student writer, or a nonlinear process, like a professional writer, as described in the Blankenship article?

3. What areas of your writing process would you like to improve or give more attention to? How do you think giving more attention to certain parts of your process would improve the quality of your writing?