Chapter 7

Communication in Relationships

More than 2,300 years ago, Aristotle wrote about the importance of friendships to society, and other Greek philosophers wrote about emotions and their effects on relationships. Although research on relationships has increased dramatically over the past few decades, the fact that these revered ancient philosophers included them in their writings illustrates the important place interpersonal relationships have in human life. Daniel Perlman and Steve Duck, “The Seven Seas of the Study of Personal Relationships: From ‘The Thousand Islands’ to Interconnected Waterways,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 13. But how do we come to form relationships with friends, family, romantic partners, and coworkers? Why are some of these relationships more exciting, stressful, enduring, or short-lived than others? Are we guided by fate, astrology, luck, personality, or other forces to the people we like and love? We’ll begin to answer those questions in this chapter.

7.1 Foundations of Relationships

Learning Objectives

Distinguish between personal and social relationships.

Describe stages of relational interaction.

Discuss social exchange theory.

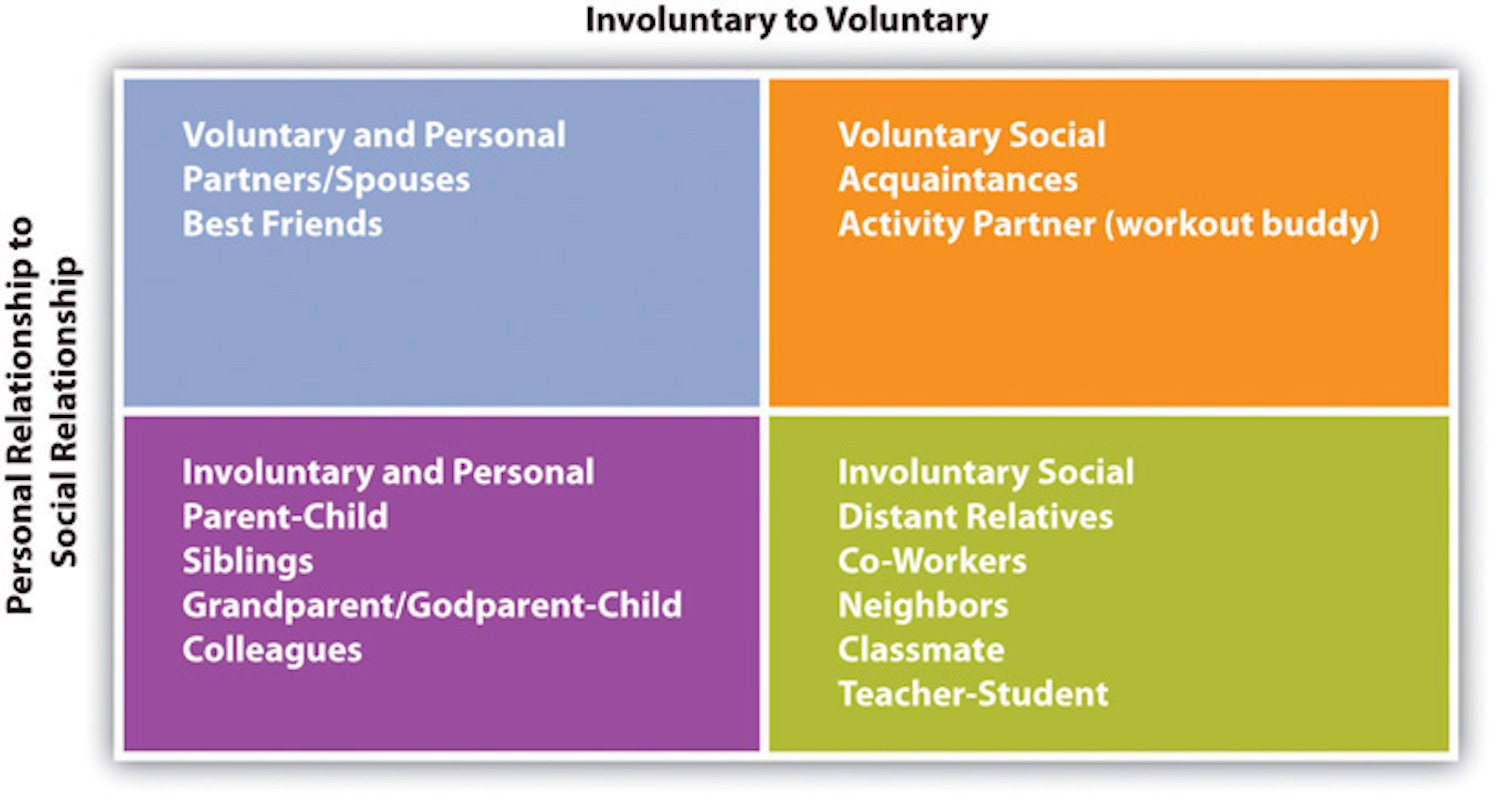

We can begin to classify key relationships we have by distinguishing between our personal and our social relationships. C. Arthur VanLear, Ascan Koerner, and Donna M. Allen, “Relationship Typologies,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 95. Personal relationships meet emotional, relational, and instrumental needs, as they are intimate, close, and interdependent relationships such as those we have with best friends, partners, or immediate family. Social relationships are relationships that occasionally meet our needs and lack the closeness and interdependence of personal relationships. Examples of social relationships include coworkers, distant relatives, and acquaintances. Another distinction useful for categorizing relationships is whether or not they are voluntary. For example, some personal relationships are voluntary, like those with romantic partners, and some are involuntary, like those with close siblings. Likewise, some social relationships are voluntary, like those with acquaintances, and some are involuntary, like those with neighbors or distant relatives. You can see how various relationships fall into each of these dimensions in Figure 7.1 “Types of Relationships”. Now that we have a better understanding of how we define relationships, we’ll examine the stages that most of our relationships go through as they move from formation to termination.

Figure 7.1Types of Relationships

Source: Adapted from C. Arthur VanLear, AscanKoerner, and Donna M. Allen, “Relationship Typologies,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 95.

Stages of Relational Interaction

Communication is at the heart of forming our interpersonal relationships. We reach the achievement of relating through the everyday conversations and otherwise trivial interactions that form the fabric of our relationships. It is through our communication that we adapt to the dynamic nature of our relational worlds, given that relational partners do not enter each encounter or relationship with compatible expectations. Communication allows us to test and be tested by our potential and current relational partners. It is also through communication that we respond when someone violates or fails to meet those expectations. Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 32–51.

There are ten established stages of interaction that can help us understand how relationships come together and come apart. Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 32–51. We will discuss each stage in more detail, but in Table 7.1 “Relationship Stages” you will find a list of the communication stages. We should keep the following things in mind about this model of relationship development: relational partners do not always go through the stages sequentially, some relationships do not experience all the stages, we do not always consciously move between stages, and coming together and coming apart are not inherently good or bad. As we have already discussed, relationships are always changing—they are dynamic. Although this model has been applied most often to romantic relationships, most relationships follow a similar pattern that may be adapted to a particular context.

Table 7.1 Relationship Stages

|

Process |

Stage |

Representative Communication |

| Coming Together | Initiating | “My name’s Rich. It’s nice to meet you.” |

| Experimenting | “I like to cook and refinish furniture in my spare time. What about you?” | |

| Intensifying | “I feel like we’ve gotten a lot closer over the past couple months.” | |

| Integrating | (To friend) “We just opened a joint bank account.” | |

| Bonding | “I can’t wait to tell my parents that we decided to get married!” | |

| Coming Apart | Differentiating | “I’d really like to be able to hang out with my friends sometimes.” |

| Circumscribing | “Don’t worry about problems I’m having at work. I can deal with it.” | |

| Stagnating | (To self) “I don’t know why I even asked him to go out to dinner. He never wants to go out and have a good time.” | |

| Avoiding | “I have a lot going on right now, so I probably won’t be home as much.” | |

| Terminating | “It’s important for us both to have some time apart. I know you’ll be fine.” | |

Source: Adapted from Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 34.

Initiating

In the initiating stage, people size each other up and try to present themselves favorably. Whether you run into someone in the hallway at school or in the produce section at the grocery store, you scan the person and consider any previous knowledge you have of them, expectations for the situation, and so on. Initiating is influenced by several factors.

If you encounter a stranger, you may say, “Hi, my name’s Rich.” If you encounter a person you already know, you’ve already gone through this before, so you may just say, “What’s up?” Time constraints also affect initiation. A quick passing calls for a quick hello, while a scheduled meeting may entail a more formal start. If you already know the person, the length of time that’s passed since your last encounter will affect your initiation. For example, if you see a friend from high school while home for winter break, you may set aside a long block of time to catch up; however, if you see someone at work that you just spoke to ten minutes earlier, you may skip initiating communication. The setting also affects how we initiate conversations, as we communicate differently at a crowded bar than we do on an airplane. Even with all this variation, people typically follow typical social scripts for interaction at this stage.

Experimenting

The scholars who developed these relational stages have likened the experimenting stage, where people exchange information and often move from strangers to acquaintances, to the “sniffing ritual” of animals. Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 38–39. A basic exchange of information is typical as the experimenting stage begins. For example, on the first day of class, you may chat with the person sitting beside you and take turns sharing your year in school, hometown, residence hall, and major. Then you may branch out and see if there are any common interests that emerge. Finding out you’re both St. Louis Cardinals fans could then lead to more conversation about baseball and other hobbies or interests; however, sometimes the experiment may fail. If your attempts at information exchange with another person during the experimenting stage are met with silence or hesitation, you may interpret their lack of communication as a sign that you shouldn’t pursue future interaction.

Experimenting continues in established relationships. Small talk, a hallmark of the experimenting stage, is common among young adults catching up with their parents when they return home for a visit or committed couples when they recount their day while preparing dinner. Small talk can be annoying sometimes, especially if you feel like you have to do it out of politeness. I have found, for example, that strangers sometimes feel the need to talk to me at the gym (even when I have ear buds in). Although I’d rather skip the small talk and just work out, I follow social norms of cheerfulness and politeness and engage in small talk. Small talk serves important functions, such as creating a communicative entry point that can lead people to uncover topics of conversation that go beyond the surface level, helping us audition someone to see if we’d like to talk to them further, and generally creating a sense of ease and community with others. And even though small talk isn’t viewed as very substantive, the authors of this model of relationships indicate that most of our relationships do not progress far beyond this point. Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 39.

Intensifying

As we enter the intensifying stage, we indicate that we would like or are open to more intimacy, and then we wait for a signal of acceptance before we attempt more intimacy. This incremental intensification of intimacy can occur over a period of weeks, months, or years and may involve inviting a new friend to join you at a party, then to your place for dinner, then to go on vacation with you. It would be seen as odd, even if the experimenting stage went well, to invite a person who you’re still getting to know on vacation with you without engaging in some less intimate interaction beforehand. In order to save face and avoid making ourselves overly vulnerable, steady progression is key in this stage. Aside from sharing more intense personal time, requests for and granting favors may also play into intensification of a relationship. For example, one friend helping the other prepare for a big party on their birthday can increase closeness. However, if one person asks for too many favors or fails to reciprocate favors granted, then the relationship can become unbalanced, which could result in a transition to another stage, such as differentiating.

Other signs of the intensifying stage include creation of nicknames, inside jokes, and personal idioms; increased use of we and our; increased communication about each other’s identities (e.g., “My friends all think you are really laid back and easy to get along with”); and a loosening of typical restrictions on possessions and personal space (e.g., you have a key to your best friend’s apartment and can hang out there if your roommate is getting on your nerves). Navigating the changing boundaries between individuals in this stage can be tricky, which can lead to conflict or uncertainty about the relationship’s future as new expectations for relationships develop. Successfully managing this increasing closeness can lead to relational integration.

Integrating

In the integrating stage, two people’s identities and personalities merge, and a sense of interdependence develops. Even though this stage is most evident in romantic relationships, there are elements that appear in other relationship forms. Some verbal and nonverbal signals of the integrating stage are when the social networks of two people merge; those outside the relationship begin to refer to or treat the relational partners as if they were one person (e.g., always referring to them together—“Let’s invite Olaf and Bettina”); or the relational partners present themselves as one unit (e.g., both signing and sending one holiday card or opening a joint bank account). Even as two people integrate, they likely maintain some sense of self by spending time with friends and family separately, which helps balance their needs for independence and connection.

Bonding

The bonding stage includes a public ritual that announces formal commitment. These types of rituals include weddings, commitment ceremonies, and civil unions. Obviously, this stage is almost exclusively applicable to romantic couples. In some ways, the bonding ritual is arbitrary, in that it can occur at any stage in a relationship. In fact, bonding rituals are often later annulled or reversed because a relationship doesn’t work out, perhaps because there wasn’t sufficient time spent in the experimenting or integrating phases. However, bonding warrants its own stage because the symbolic act of bonding can have very real effects on how two people communicate about and perceive their relationship. For example, the formality of the bond may lead the couple and those in their social network to more diligently maintain the relationship if conflict or stress threatens it.

Differentiating

Individual differences can present a challenge at any given stage in the relational interaction model; however, in the differentiating stage, communicating these differences becomes a primary focus. Differentiating is the reverse of integrating, as we and our reverts back to I and my. People may try to reboundary some of their life prior to the integrating of the current relationship, including other relationships or possessions. For example, Carrie may reclaim friends who became “shared” as she got closer to her roommate Julie and their social networks merged by saying, “I’m having my friends over to the apartment and would like to have privacy for the evening.” Differentiating may onset in a relationship that bonded before the individuals knew each other in enough depth and breadth. Even in relationships where the bonding stage is less likely to be experienced, such as a friendship, unpleasant discoveries about the other person’s past, personality, or values during the integrating or experimenting stage could lead a person to begin differentiating.

Circumscribing

To circumscribe means to draw a line around something or put a boundary around it. Oxford English Dictionary Online, accessed September 13, 2011, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/circumscribe. So in the circumscribing stage, communication decreases and certain areas or subjects become restricted as individuals verbally close themselves off from each other. They may say things like “I don’t want to talk about that anymore” or “You mind your business and I’ll mind mine.” If one person was more interested in differentiating in the previous stage, or the desire to end the relationship is one-sided, verbal expressions of commitment may go unechoed—for example, when one person’s statement, “I know we’ve had some problems lately, but I still like being with you,” is met with silence. Passive-aggressive behavior and the demand-withdrawal conflict pattern, which we discussed in Chapter 6 “Interpersonal Communication Processes”, may occur more frequently in this stage. Once the increase in boundaries and decrease in communication becomes a pattern, the relationship further deteriorates toward stagnation.

Stagnating

During the stagnating stage, the relationship may come to a standstill, as individuals basically wait for the relationship to end. Outward communication may be avoided, but internal communication may be frequent. The relational conflict flaw of mindreading takes place as a person’s internal thoughts lead them to avoid communication. For example, a person may think, “There’s no need to bring this up again, because I know exactly how he’ll react!” This stage can be prolonged in some relationships. Parents and children who are estranged, couples who are separated and awaiting a divorce, or friends who want to end a relationship but don’t know how to do it may have extended periods of stagnation. Short periods of stagnation may occur right after a failed exchange in the experimental stage, where you may be in a situation that’s not easy to get out of, but the person is still there. Although most people don’t like to linger in this unpleasant stage, some may do so to avoid potential pain from termination, some may still hope to rekindle the spark that started the relationship, or some may enjoy leading their relational partner on.

Avoiding

Moving to the avoiding stage may be a way to end the awkwardness that comes with stagnation, as people signal that they want to close down the lines of communication. Communication in the avoiding stage can be very direct—“I don’t want to talk to you anymore”—or more indirect—“I have to meet someone in a little while, so I can’t talk long.” While physical avoidance such as leaving a room or requesting a schedule change at work may help clearly communicate the desire to terminate the relationship, we don’t always have that option. In a parent-child relationship, where the child is still dependent on the parent, or in a roommate situation, where a lease agreement prevents leaving, people may engage in cognitive dissociation, which means they mentally shut down and ignore the other person even though they are still physically copresent.

Terminating

The terminating stage of a relationship can occur shortly after initiation or after a ten- or twenty-year relational history has been established. Termination can result from outside circumstances such as geographic separation or internal factors such as changing values or personalities that lead to a weakening of the bond. Termination exchanges involve some typical communicative elements and may begin with a summary message that recaps the relationship and provides a reason for the termination (e.g., “We’ve had some ups and downs over our three years together, but I’m getting ready to go to college, and I either want to be with someone who is willing to support me, or I want to be free to explore who I am.”). The summary message may be followed by a distance message that further communicates the relational drift that has occurred (e.g., “We’ve really grown apart over the past year”), which may be followed by a disassociation message that prepares people to be apart by projecting what happens after the relationship ends (e.g., “I know you’ll do fine without me. You can use this time to explore your options and figure out if you want to go to college too or not.”). Finally, there is often a message regarding the possibility for future communication in the relationship (e.g., “I think it would be best if we don’t see each other for the first few months, but text me if you want to.”). Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 46–47. These ten stages of relational development provide insight into the complicated processes that affect relational formation and deterioration. We also make decisions about our relationships by weighing costs and rewards.

Social Exchange Theory

Social exchange theory essentially entails a weighing of the costs and rewards in a given relationship. John H. Harvey and Amy Wenzel, “Theoretical Perspectives in the Study of Close Relationships,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 38–39. Rewards are outcomes that we get from a relationship that benefit us in some way, while costs range from granting favors to providing emotional support. When we do not receive the outcomes or rewards that we think we deserve, then we may negatively evaluate the relationship, or at least a given exchange or moment in the relationship, and view ourselves as being underbenefited. In an equitable relationship, costs and rewards are balanced, which usually leads to a positive evaluation of the relationship and satisfaction.

Commitment and interdependence are important interpersonal and psychological dimensions of a relationship that relate to social exchange theory. Interdependence refers to the relationship between a person’s well-being and involvement in a particular relationship. A person will feel interdependence in a relationship when (1) satisfaction is high or the relationship meets important needs; (2) the alternatives are not good, meaning the person’s needs couldn’t be met without the relationship; or (3) investment in the relationship is high, meaning that resources might decrease or be lost without the relationship. John H. Harvey and Amy Wenzel, “Theoretical Perspectives in the Study of Close Relationships,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 40.

We can be cautioned, though, to not view social exchange theory as a tit-for-tat accounting of costs and rewards. Patricia Noller, “Bringing It All Together: A Theoretical Approach,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 770. We wouldn’t be very good relational partners if we carried around a little notepad, notating each favor or good deed we completed so we can expect its repayment. As noted earlier, we all become aware of the balance of costs and rewards at some point in our relationships, but that awareness isn’t persistent. We also have communal relationships, in which members engage in a relationship for mutual benefit and do not expect returns on investments such as favors or good deeds. John H. Harvey and Amy Wenzel, “Theoretical Perspectives in the Study of Close Relationships,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 38. As the dynamics in a relationship change, we may engage communally without even being aware of it, just by simply enjoying the relationship. It has been suggested that we become more aware of the costs and rewards balance when a relationship is going through conflict. Patricia Noller, “Bringing It All Together: A Theoretical Approach,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 770. Overall, relationships are more likely to succeed when there is satisfaction and commitment, meaning that we are pleased in a relationship intrinsically or by the rewards we receive.

Key Takeaways

Personal relationships are close, intimate, and interdependent, meeting many of our interpersonal needs.

There are stages of relational interaction in which relationships come together (initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, and bonding) and come apart (differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, and terminating).

The weighing of costs and rewards in a relationship affects commitment and overall relational satisfaction.

Exercises

Review the types of relationships in Figure 7.1 “Types of Relationships”. Name at least one person from your relationships that fits into each quadrant. How does your communication differ between each of these people?

Pick a relationship important to you and determine what stage of relational interaction you are currently in with that person. What communicative signals support your determination? What other stages from the ten listed have you experienced with this person?

How do you weigh the costs and rewards in your relationships? What are some rewards you are currently receiving from your closest relationships? What are some costs?

7.2 Communication and Friends

Learning Objectives

Compare and contrast different types of friendships.

Describe the cycle of friendship from formation to maintenance to dissolution/deterioration.

Explain how culture and gender influence friendships.

Do you consider all the people you are “friends” with on Facebook to be friends? What’s the difference, if any, between a “Facebook friend” and a real-world friend? Friendships, like other relationship forms, can be divided into categories. What’s the difference between a best friend, a good friend, and an old friend? What about work friends, school friends, and friends of the family? It’s likely that each of you reading this book has a different way of perceiving and categorizing your friendships. In this section, we will learn about the various ways we classify friends, the life cycle of friendships, and how gender affects friendships.

Defining and Classifying Friends

Friendships are voluntary interpersonal relationships between two people who are usually equals and who mutually influence one another. William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 11–12. Friendships are distinct from romantic relationships, family relationships, and acquaintances and are often described as more vulnerable relationships than others due to their voluntary nature, the availability of other friends, and the fact that they lack the social and institutional support of other relationships. The lack of official support for friendships is not universal, though. In rural parts of Thailand, for example, special friendships are recognized by a ceremony in which both parties swear devotion and loyalty to each other. Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 2. Even though we do not have a formal ritual to recognize friendship in the United States, in general, research shows that people have three main expectations for close friendships. A friend is someone you can talk to, someone you can depend on for help and emotional support, and someone you can participate in activities and have fun with. William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 271.

Although friendships vary across the life span, three types of friendships are common in adulthood: reciprocal, associative, and receptive. Adapted from C. Arthur VanLear, Ascan Koerner, and Donna M. Allen, “Relationship Typologies,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 103. Reciprocal friendships are solid interpersonal relationships between people who are equals with a shared sense of loyalty and commitment. These friendships are likely to develop over time and can withstand external changes such as geographic separation or fluctuations in other commitments such as work and childcare. Reciprocal friendships are what most people would consider the ideal for best friends. Associative friendships are mutually pleasurable relationships between acquaintances or associates that, although positive, lack the commitment of reciprocal friendships. These friendships are likely to be maintained out of convenience or to meet instrumental goals.

For example, a friendship may develop between two people who work out at the same gym. They may spend time with each other in this setting a few days a week for months or years, but their friendship might end if the gym closes or one person’s schedule changes. Receptive friendships include a status differential that makes the relationship asymmetrical. Unlike the other friendship types that are between peers, this relationship is more like that of a supervisor-subordinate or clergy-parishioner. In some cases, like a mentoring relationship, both parties can benefit from the relationship. In other cases, the relationship could quickly sour if the person with more authority begins to abuse it.

A relatively new type of friendship, at least in label, is the “friends with benefits” relationship. Friends with benefits (FWB) relationships have the closeness of a friendship and the sexual activity of a romantic partnership without the expectations of romantic commitment or labels. Justin J. Lehmiller, Laura E. VanderDrift, and Janice R. Kelly, “Sex Differences in Approaching Friends with Benefits Relationships,” Journal of Sex Research 48, no. 2–3 (2011): 276. FWB relationships are hybrids that combine characteristics of romantic and friend pairings, which produces some unique dynamics. In my conversations with students over the years, we have talked through some of the differences between friends, FWB, and hook-up partners, or what we termed “just benefits.” Hook-up or “just benefits” relationships do not carry the emotional connection typical in a friendship, may occur as one-night-stands or be regular things, and exist solely for the gratification and/or convenience of sexual activity. So why might people choose to have or avoid FWB relationships?

Various research studies have shown that half of the college students who participated have engaged in heterosexual FWB relationships. Melissa A. Bisson and Timothy R. Levine, “Negotiating a Friends with Benefits Relationship,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 38 (2009): 67. Many who engage in FWB relationships have particular views on love and sex—namely, that sex can occur independently of love. Conversely, those who report no FWB relationships often cite religious, moral, or personal reasons for not doing so. Some who have reported FWB relationships note that they value the sexual activity with their friend, and many feel that it actually brings the relationship closer. Despite valuing the sexual activity, they also report fears that it will lead to hurt feelings or the dissolution of a friendship. Justin J. Lehmiller, Laura E. VanderDrift, and Janice R. Kelly, “Sex Differences in Approaching Friends with Benefits Relationships,” Journal of Sex Research 48, no. 2–3 (2011): 276. We must also consider gender differences and communication challenges in FWB relationships.

Gender biases must be considered when discussing heterosexual FWB relationships, given that women in most societies are judged more harshly than men for engaging in casual sex. But aside from dealing with the double standard that women face regarding their sexual activity, there aren’t many gender differences in how men and women engage in and perceive FWB relationships. So what communicative patterns are unique to the FWB relationship? Those who engage in FWB relationships have some unique communication challenges. For example, they may have difficulty with labels as they figure out whether they are friends, close friends, a little more than friends, and so on. Research participants currently involved in such a relationship reported that they have more commitment to the friendship than the sexual relationship. But does that mean they would give up the sexual aspect of the relationship to save the friendship? The answer is “no” according to the research study. Most participants reported that they would like the relationship to stay the same, followed closely by the hope that it would turn into a full romantic relationship. Justin J. Lehmiller, Laura E. VanderDrift, and Janice R. Kelly, “Sex Differences in Approaching Friends with Benefits Relationships,” Journal of Sex Research 48, no. 2–3 (2011): 280. Just from this study, we can see that there is often a tension between action and labels. In addition, those in a FWB relationship often have to engage in privacy management as they decide who to tell and who not to tell about their relationship, given that some mutual friends are likely to find out and some may be critical of the relationship. Last, they may have to establish ground rules or guidelines for the relationship. Since many FWB relationships are not exclusive, meaning partners are open to having sex with other people, ground rules or guidelines may include discussions of safer-sex practices, disclosure of sexual partners, or periodic testing for sexually transmitted infections.

The Life Span of Friendships

Friendships, like most relationships, have a life span ranging from formation to maintenance to deterioration/dissolution. Friendships have various turning points that affect their trajectory. While there are developmental stages in friendships, they may not be experienced linearly, as friends can cycle through formation, maintenance, and deterioration/dissolution together or separately and may experience stages multiple times. Friendships are also diverse, in that not all friendships develop the same level of closeness, and the level of closeness can fluctuate over the course of a friendship. Changes in closeness can be an expected and accepted part of the cycle of friendships, and less closeness doesn’t necessarily lead to less satisfaction. Amy Janan Johnson, Elaine Wittenberg, Melinda Morris Villagran, Michelle Mazur, and Paul Villagran, “Relational Progression as a Dialectic: Examining Turning Points in Communication among Friends,” Communication Monographs 70, no. 3 (2003): 245.

The formation process of friendship development involves two people moving from strangers toward acquaintances and potentially friends. Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 15. Several factors influence the formation of friendships, including environmental, situational, individual, and interactional factors. Beverly Fehr, “The Life Cycle of Friendship,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 71–74. Environmental factors lead us to have more day-to-day contact with some people over others. For example, residential proximity and sharing a workplace are catalysts for friendship formation. Thinking back to your childhood, you may have had early friendships with people on your block because they were close by and you could spend time together easily without needing transportation. A similar situation may have occurred later if you moved away from home for college and lived in a residence hall.

You may have formed early relationships, perhaps even before classes started, with hall-mates or dorm-mates. I’ve noticed that many students will continue to associate and maybe even attempt to live close to friends they made in their first residence hall throughout their college years, even as they move residence halls or off campus. We also find friends through the social networks of existing friends and family. Although these people may not live close to us, they are brought into proximity through people we know, which facilitates our ability to spend time with them. Encountering someone due to environmental factors may lead to a friendship if the situational factors are favorable.

The main situational factor that may facilitate or impede friendship formation is availability. Initially, we are more likely to be interested in a friendship if we anticipate that we’ll be able to interact with the other person again in the future without expending more effort than our schedule and other obligations will allow. In order for a friendship to take off, both parties need resources such as time and energy to put into it. Hectic work schedules, family obligations, or personal stresses such as financial problems or family or relational conflict may impair someone’s ability to nurture a friendship.

The number of friends we have at any given point is a situational factor that also affects whether or not we are actually looking to add new friends. I have experienced this fluctuation. Since I stayed in the same city for my bachelor’s and master’s degrees, I had forged many important friendships over those seven years. In the last year of my master’s program, I was immersed in my own classes and jobs as a residence hall director and teaching assistant. I was also preparing to move within the year to pursue my doctorate. I recall telling a friend of many years that I was no longer “accepting applications” for new friends. Although I was half-joking, this example illustrates the importance of environmental and situational factors. Not only was I busier than I had ever been; I was planning on moving and therefore knew it wouldn’t be easy to continue investing in any friendships I made in my final year. Instead, I focused on the friendships I already had and attended to my other personal obligations. Of course, when I moved to a new city a few months later, I was once again “accepting applications,” because I had lost the important physical proximity to all my previous friends. Environmental and situational factors that relate to friendship formation point to the fact that convenience plays a large role in determining whether a relationship will progress or not.

While contact and availability may initiate communication with a potential friend, individual and interactional factors are also important. We are more likely to develop friendships with individuals we deem physically attractive, socially competent, and responsive to our needs. Beverly Fehr, “The Life Cycle of Friendship,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 72. Specifically, we are more attracted to people we deem similar to or slightly above us in terms of attractiveness and competence. Although physical attractiveness is more important in romantic relationships, research shows that we evaluate attractive people more positively, which may influence our willingness to invest more in a friendship. Friendships also tend to form between people with similar demographic characteristics such as race, gender, age, and class, and similar personal characteristics like interests and values. Being socially competent and responsive in terms of empathy, emotion management, conflict management, and self-disclosure also contribute to the likelihood of friendship development.

If a friendship is established in the formation phase, then the new friends will need to maintain their relationship. The maintenance phase includes the most variation in terms of the processes that take place, the commitment to maintenance from each party, and the length of time of the phase. Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 15. In short, some friendships require more maintenance in terms of shared time together and emotional support than other friendships that can be maintained with only occasional contact. Maintenance is important, because friendships provide important opportunities for social support that take the place of or supplement family and romantic relationships. Sometimes, we may feel more comfortable being open with a friend about something than we would with a family member or romantic partner. Most people expect that friends will be there for them when needed, which is the basis of friendship maintenance. As with other relationships, tasks that help maintain friendships range from being there in a crisis to seemingly mundane day-to-day activities and interactions.

Failure to perform or respond to friendship-maintenance tasks can lead to the deterioration and eventual dissolution of friendships. Causes of dissolution may be voluntary (termination due to conflict), involuntary (death of friendship partner), external (increased family or work commitments), or internal (decreased liking due to perceived lack of support). Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 16. While there are often multiple, interconnecting causes that result in friendship dissolution, there are three primary sources of conflict in a friendship that stem from internal/interpersonal causes and may lead to voluntary dissolution: sexual interference, failure to support, and betrayal of trust. Beverly Fehr, “The Life Cycle of Friendship,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 78. Sexual interference generally involves a friend engaging with another friend’s romantic partner or romantic interest and can lead to feelings of betrayal, jealousy, and anger. Failure to support may entail a friend not coming to another’s aid or defense when criticized. Betrayal of trust can stem from failure to secure private information by telling a secret or disclosing personal information without permission. While these three internal factors may initiate conflict in a friendship, discovery of unfavorable personal traits can also lead to problems.

Have you ever started investing in a friendship only to find out later that the person has some character flaws that you didn’t notice before? As was mentioned earlier, we are more likely to befriend someone whose personal qualities we find attractive. However, we may not get to experience the person in a variety of contexts and circumstances before we invest in the friendship. We may later find out that our easygoing friend becomes really possessive once we start a romantic relationship and spend less time with him. Or we may find that our happy-go-lucky friend gets moody and irritable when she doesn’t get her way. These individual factors become interactional when our newly realized dissimilarity affects our communication. It is logical that as our liking decreases, as a result of personal reassessment of the friendship, we will engage in less friendship-maintenance tasks such as self-disclosure and supportive communication. In fact, research shows that the main termination strategy employed to end a friendship is avoidance. As we withdraw from the relationship, the friendship fades away and may eventually disappear, which is distinct from romantic relationships, which usually have an official “breakup.” Aside from changes based on personal characteristics discovered through communication, changes in the external factors that help form friendships can also lead to their dissolution.

The main change in environmental factors that can lead to friendship dissolution is a loss of proximity, which may entail a large or small geographic move or school or job change. The two main situational changes that affect friendships are schedule changes and changes in romantic relationships. Even without a change in environment, someone’s job or family responsibilities may increase, limiting the amount of time one has to invest in friendships. Additionally, becoming invested in a romantic relationship may take away from time previously allocated to friends. For environmental and situational changes, the friendship itself is not the cause of the dissolution. These external factors are sometimes difficult if not impossible to control, and lost or faded friendships are a big part of everyone’s relational history.

Gender and Friendship

Gender influences our friendships and has received much attention, as people try to figure out how different men and women’s friendships are. There is a conception that men’s friendships are less intimate than women’s based on the stereotype that men do not express emotions. In fact, men report a similar amount of intimacy in their friendships as women but are less likely than women to explicitly express affection verbally (e.g., saying “I love you”) and nonverbally (e.g., through touching or embracing) toward their same-gender friends. Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 20. This is not surprising, given the societal taboos against same-gender expressions of affection, especially between men, even though an increasing number of men are more comfortable expressing affection toward other men and women. However, researchers have wondered if men communicate affection in more implicit ways that are still understood by the other friend. Men may use shared activities as a way to express closeness—for example, by doing favors for each other, engaging in friendly competition, joking, sharing resources, or teaching each other new skills. Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 69. Some scholars have argued that there is a bias toward viewing intimacy as feminine, which may have skewed research on men’s friendships. While verbal expressions of intimacy through self-disclosure have been noted as important features of women’s friendships, activity sharing has been the focus in men’s friendships. This research doesn’t argue that one gender’s friendships are better than the other’s, and it concludes that the differences shown in the research regarding expressions of intimacy are not large enough to impact the actual practice of friendships. Michael Monsour, “Communication and Gender among Adult Friends,” in The Sage Handbook of Gender and Communication, eds. Bonnie J. Dow and Julia T. Wood (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 63.

Cross-gender friendships are friendships between a male and a female. These friendships diminish in late childhood and early adolescence as boys and girls segregate into separate groups for many activities and socializing, reemerge as possibilities in late adolescence, and reach a peak potential in the college years of early adulthood. Later, adults with spouses or partners are less likely to have cross-sex friendships than single people. William K. Rawlins, Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1992), 182. In any case, research studies have identified several positive outcomes of cross-gender friendships. Men and women report that they get a richer understanding of how the other gender thinks and feels. Panayotis Halatsis and Nicolas Christakis, “The Challenge of Sexual Attraction within Heterosexuals’ Cross-Sex Friendship,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 26, no. 6–7 (2009): 920. It seems these friendships fulfill interaction needs not as commonly met in same-gender friendships. For example, men reported more than women that they rely on their cross-gender friendships for emotional support. Rosemary Bleiszner and Rebecca G. Adams, Adult Friendship (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 68. Similarly, women reported that they enjoyed the activity-oriented friendships they had with men. Panayotis Halatsis and Nicolas Christakis, “The Challenge of Sexual Attraction within Heterosexuals’ Cross-Sex Friendship,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 26, no. 6–7 (2009): 920.

As discussed earlier regarding friends-with-benefits relationships, sexual attraction presents a challenge in cross-gender heterosexual friendships. Even if the friendship does not include sexual feelings or actions, outsiders may view the relationship as sexual or even encourage the friends to become “more than friends.” Aside from the pressures that come with sexual involvement or tension, the exaggerated perceptions of differences between men and women can hinder cross-gender friendships. However, if it were true that men and women are too different to understand each other or be friends, then how could any long-term partnership such as husband/wife, mother/son, father/daughter, or brother/sister be successful or enjoyable?

Key Takeaways

Friendship formation, maintenance, and deterioration/dissolution are influenced by environmental, situational, and interpersonal factors.

Cross-gender friendships may offer perspective into gender relationships that same-gender friendships do not, as both men and women report that they get support or enjoyment from their cross-gender friendships. However, there is a potential for sexual tension that complicates these relationships.

EXERCISES

Exercises

Have you ever been in a situation where you didn’t feel like you could “accept applications” for new friends or were more eager than normal to “accept applications” for new friends? What were the environmental or situational factors that led to this situation?

Getting integrated: Review the types of friendships (reciprocal, associative, and receptive). Which of these types of friendships do you have more of in academic contexts and why? Answer the same question for professional contexts and personal contexts.

7.3 Romantic Relationships

Learning Objectives

Discuss the influences on attraction and romantic partner selection.

Discuss the differences between passionate, companionate, and romantic love.

Explain how social networks affect romantic relationships.

Explain how sexual orientation and race and ethnicity affect romantic relationships.

Romance has swept humans off their feet for hundreds of years, as is evidenced by countless odes written by love-struck poets, romance novels, and reality television shows like The Bachelor and The Bachelorette. Whether pining for love in the pages of a diary or trying to find a soul mate from a cast of suitors, love and romance can seem to take us over at times. As we have learned, communication is the primary means by which we communicate emotion, and it is how we form, maintain, and end our relationships. In this section, we will explore the communicative aspects of romantic relationships including love, sex, social networks, and cultural influences.

Relationship Formation and Maintenance

Much of the research on romantic relationships distinguishes between premarital and marital couples. However, given the changes in marriage and the diversification of recognized ways to couple, I will use the following distinctions: dating, cohabitating, and partnered couples. The category for dating couples encompasses the courtship period, which may range from a first date through several years. Once a couple moves in together, they fit into the category of cohabitating couple. Partnered couples take additional steps to verbally, ceremonially, or legally claim their intentions to be together in a long-term committed relationship. The romantic relationships people have before they become partnered provide important foundations for later relationships. But how do we choose our romantic partners, and what communication patterns affect how these relationships come together and apart?

Family background, values, physical attractiveness, and communication styles are just some of the factors that influence our selection of romantic relationships. Chris Segrin and Jeanne Flora, Family Communication (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2005), 106. Attachment theory, as discussed earlier, relates to the bond that a child feels with their primary caregiver. Research has shown that the attachment style (secure, anxious, or avoidant) formed as a child influences adult romantic relationships. Other research shows that adolescents who feel like they have a reliable relationship with their parents feel more connection and attraction in their adult romantic relationships. Inge Seiffge-Krenke, Shmuel Shulman, and Nicolai Kiessinger, “Adolescent Precursors of Romantic Relationships in Young Adulthood,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 18, no. 3 (2001): 327–46. Aside from attachment, which stems more from individual experiences as a child, relationship values, which stem more from societal expectations and norms, also affect romantic attraction.

We can see the important influence that communication has on the way we perceive relationships by examining the ways in which relational values have changed over recent decades. Over the course of the twentieth century, for example, the preference for chastity as a valued part of relationship selection decreased significantly. While people used to indicate that it was very important that the person they partner with not have had any previous sexual partners, today people list several characteristics they view as more important in mate selection. Chris Segrin and Jeanne Flora, Family Communication (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2005), 107. In addition, characteristics like income and cooking/housekeeping skills were once more highly rated as qualities in a potential mate. Today, mutual attraction and love are the top mate-selection values.

In terms of mutual attraction, over the past sixty years, men and women have more frequently reported that physical attraction is an important aspect of mate selection. But what characteristics lead to physical attraction? Despite the saying that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” there is much research that indicates body and facial symmetry are the universal basics of judging attractiveness. Further, the matching hypothesis states that people with similar levels of attractiveness will pair together despite the fact that people may idealize fitness models or celebrities who appear very attractive. Elaine Walster, Vera Aronson, Darcy Abrahams, and Leon Rottman, “Importance of Physical Attractiveness in Dating Behavior,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 4, no. 5 (1966): 508–16. However, judgments of attractiveness are also communicative and not just physical. Other research has shown that verbal and nonverbal expressiveness are judged as attractive, meaning that a person’s ability to communicate in an engaging and dynamic way may be able to supplement for some lack of physical attractiveness. In order for a relationship to be successful, the people in it must be able to function with each other on a day-to-day basis, once the initial attraction stage is over. Similarity in preferences for fun activities and hobbies like attending sports and cultural events, relaxation, television and movie tastes, and socializing were correlated to more loving and well-maintained relationships. Similarity in role preference means that couples agree whether one or the other or both of them should engage in activities like indoor and outdoor housekeeping, cooking, and handling the finances and shopping. Couples who were not similar in these areas reported more conflict in their relationship. Chris Segrin and Jeanne Flora, Family Communication (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2005), 112.

“Getting Critical”

Arranged Marriages

Although romantic love is considered a precursor to marriage in Western societies, this is not the case in other cultures. As was noted earlier, mutual attraction and love are the most important factors in mate selection in research conducted in the United States. In some other countries, like China, India, and Iran, mate selection is primarily decided by family members and may be based on the evaluation of a potential partner’s health, financial assets, social status, or family connections. In some cases, families make financial arrangements to ensure the marriage takes place. Research on marital satisfaction of people in autonomous (self-chosen) marriages and arranged marriages has been mixed, but a recent study found that there was no significant difference in marital satisfaction between individuals in marriages of choice in the United States and those in arranged marriages in India. Jane E. Myers, Jayamala Madathil, and Lynne R. Tingle, “Marriage Satisfaction and Wellness in India and the United States: A Preliminary Comparison of Arranged Marriages and Marriages of Choice,” Journal of Counseling and Development 83 (2005): 183–87. While many people undoubtedly question whether a person can be happy in an arranged marriage, in more collectivistic (group-oriented) societies, accommodating family wishes may be more important than individual preferences. Rather than love leading up to a marriage, love is expected to grow as partners learn more about each other and adjust to their new lives together once married.

Do you think arranged marriages are ethical? Why or why not?

Try to step back and view both types of marriages from an outsider’s perspective. The differences between the two types of marriage are fairly clear, but in what ways are marriages of choice and arranged marriages similar?

List potential benefits and drawbacks of marriages of choice and arranged marriages.

Love and Sexuality in Romantic Relationships

When most of us think of romantic relationships, we think about love. However, love did not need to be a part of a relationship for it to lead to marriage until recently. In fact, marriages in some cultures are still arranged based on pedigree (family history) or potential gain in money or power for the couple’s families. Today, love often doesn’t lead directly to a partnership, given that most people don’t partner with their first love. Love, like all emotions, varies in intensity and is an important part of our interpersonal communication.

To better understand love, we can make a distinction between passionate love and companionate love. Susan S. Hendrick and Clyde Hendrick, “Romantic Love,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 204–5. Passionate love entails an emotionally charged engagement between two people that can be both exhilarating and painful. For example, the thrill of falling for someone can be exhilarating, but feelings of vulnerability or anxiety that the love may not be reciprocated can be painful. Companionate love is affection felt between two people whose lives are interdependent. For example, romantic partners may come to find a stable and consistent love in their shared time and activities together. The main idea behind this distinction is that relationships that are based primarily on passionate love will terminate unless the passion cools overtime into a more enduring and stable companionate love. This doesn’t mean that passion must completely die out for a relationship to be successful long term. In fact, a lack of passion could lead to boredom or dissatisfaction. Instead, many people enjoy the thrill of occasional passion in their relationship but may take solace in the security of a love that is more stable. While companionate love can also exist in close relationships with friends and family members, passionate love is often tied to sexuality present in romantic relationships.

There are many ways in which sexuality relates to romantic relationships and many opinions about the role that sexuality should play in relationships, but this discussion focuses on the role of sexuality in attraction and relational satisfaction. Compatibility in terms of sexual history and attitudes toward sexuality are more important predictors of relationship formation. For example, if a person finds out that a romantic interest has had a more extensive sexual history than their own, they may not feel compatible, which could lessen attraction. Susan Sprecher and Pamela C. Regan, “Sexuality in a Relational Context,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 217–19. Once together, considerable research suggests that a couple’s sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction are linked such that sexually satisfied individuals report a higher quality relationship, including more love for their partner and more security in the future success of their relationship. Susan Sprecher and Pamela C. Regan, “Sexuality in a Relational Context,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 221. While sexual activity often strengthens emotional bonds between romantic couples, it is clear that romantic emotional bonds can form in the absence of sexual activity and sexual activity is not the sole predictor of relational satisfaction. In fact, sexual communication may play just as important a role as sexual activity. Sexual communication deals with the initiation or refusal of sexual activity and communication about sexual likes and dislikes. Susan Sprecher and Pamela C. Regan, “Sexuality in a Relational Context,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 222. For example, a sexual communication could involve a couple discussing a decision to abstain from sexual activity until a certain level of closeness or relational milestone (like marriage) has been reached. Sexual communication could also involve talking about sexual likes and dislikes. Sexual conflict can result when couples disagree over frequency or type of sexual activities. Sexual conflict can also result from jealousy if one person believes their partner is focusing sexual thoughts or activities outside of the relationship. While we will discuss jealousy and cheating more in the section on the dark side of relationships, it is clear that love and sexuality play important roles in our romantic relationships.

Romantic Relationships and Social Networks

Social networks influence all our relationships but have gotten special attention in research on romantic relations. Romantic relationships are not separate from other interpersonal connections to friends and family. Is it better for a couple to share friends, have their own friends, or attempt a balance between the two? Overall, research shows that shared social networks are one of the strongest predictors of whether or not a relationship will continue or terminate.

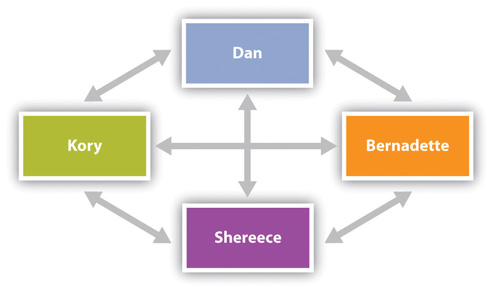

Network overlap refers to the number of shared associations, including friends and family, that a couple has. Robert M. Milardo and Heather Helms-Erikson, “Network Overlap and Third-Party Influence in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 33. For example, if Dan and Shereece are both close with Dan’s sister Bernadette, and all three of them are friends with Kory, then those relationships completely overlap (see Figure 7.3 “Social Network Overlap”).

Figure 7.3Social Network Overlap

Network overlap creates some structural and interpersonal elements that affect relational outcomes. Friends and family who are invested in both relational partners may be more likely to support the couple when one or both parties need it. In general, having more points of connection to provide instrumental support through the granting of favors or emotional support in the form of empathetic listening and validation during times of conflict can help a couple manage common stressors of relationships that may otherwise lead a partnership to deteriorate. Robert M. Milardo and Heather Helms-Erikson, “Network Overlap and Third-Party Influence in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 37.

In addition to providing a supporting structure, shared associations can also help create and sustain a positive relational culture. For example, mutual friends of a couple may validate the relationship by discussing the partners as a “couple” or “pair” and communicate their approval of the relationship to the couple separately or together, which creates and maintains a connection. Robert M. Milardo and Heather Helms-Erikson, “Network Overlap and Third-Party Influence in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 39. Being in the company of mutual friends also creates positive feelings between the couple, as their attention is taken away from the mundane tasks of work and family life. Imagine Dan and Shereece host a board-game night with a few mutual friends in which Dan wows the crowd with charades, and Kory says to Shereece, “Wow, he’s really on tonight. It’s so fun to hang out with you two.” That comment may refocus attention onto the mutually attractive qualities of the pair and validate their continued interdependence.

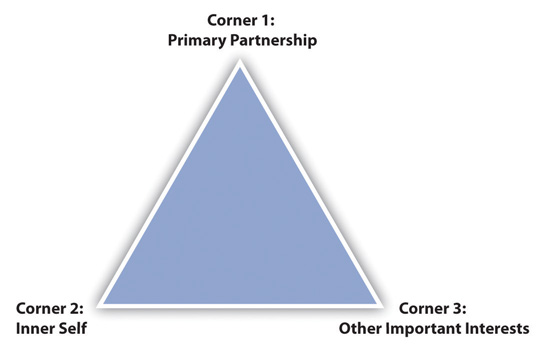

Interdependence and relationship networks can also be illustrated through the theory of triangles (see Figure 7.4 “Theory of Triangles”), which examines the relationship between three domains of activity: the primary partnership (corner 1), the inner self (corner 2), and important outside interests (corner 3). Stephen R. Marks, Three Corners: Exploring Marriage and the Self (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1986), 5.

Figure 7.4 Theory of Triangles

All of the corners interact with each other, but it is the third corner that connects the primary partnership to an extended network. For example, the inner self (corner 2) is enriched by the primary partnership (corner 1) but also gains from associations that provide support or a chance for shared activities or recreation (corner 3) that help affirm a person’s self-concept or identity. Additionally, the primary partnership (corner 1) is enriched by the third-corner associations that may fill gaps not met by the partnership. When those gaps are filled, a partner may be less likely to focus on what they’re missing in their primary relationship. However, the third corner can also produce tension in a relationship if, for example, the other person in a primary partnership feels like they are competing with their partner’s third-corner relationships. During times of conflict, one or both partners may increase their involvement in their third corner, which may have positive or negative effects. A strong romantic relationship is good, but research shows that even when couples are happily married they reported loneliness if they were not connected to friends. While the dynamics among the three corners change throughout a relationship, they are all important.

Key Takeaways

Family background, values, physical attractiveness, and communication styles influence our attraction to and selection of romantic partners.

Network overlap is an important predictor of relational satisfaction and success.

Exercises

In terms of romantic attraction, which adage do you think is more true and why? “Birds of a feather flock together” or “Opposites attract.”

List some examples of how you see passionate and companionate love play out in television shows or movies. Do you think this is an accurate portrayal of how love is experienced in romantic relationships? Why or why not?

Social network overlap affects a romantic relationship in many ways. What are some positives and negatives of network overlap?

7.4 The Dark Side of Relationships

Learning Objectives

Define the dark side of relationships.

Explain how lying affects relationships.

Explain how sexual and emotional cheating affects relationships.

Define the various types of interpersonal violence and explain how they are similar and different.

In the course of a given day, it is likely that we will encounter the light and dark sides of interpersonal relationships. So what constitutes the dark side of relationships? There are two dimensions of the dark side of relationships: one is the degree to which something is deemed acceptable or not by society; the other includes the degree to which something functions productively to improve a relationship or not. Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach, “Disentangling the Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication,” in The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, eds. Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2007), 5. These dimensions become more complicated when we realize that there can be overlap between them, meaning that it may not always be easy to identify something as exclusively light or dark.

Some communication patterns may be viewed as appropriate by society but still serve a relationally destructive function. Our society generally presumes that increased understanding of a relationship and relational partner would benefit the relationship. However, numerous research studies have found that increased understanding of a relationship and relational partner may be negative. In fact, by avoiding discussing certain topics that might cause conflict, some couples create and sustain positive illusions about their relationship that may cover up a darker reality. Despite this, the couple may report that they are very satisfied with their relationship. In this case, the old saying “ignorance is bliss” seems appropriate. Likewise, communication that is presumed inappropriate by society may be productive for a given relationship. Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach, “Disentangling the Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication,” in The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, eds. Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2007), 5–6. For example, our society ascribes to an ideology of openness that promotes honesty. However, as we will discuss more next, honesty may not always be the best policy. Lies intended to protect a relational partner (called altruistic lies) may net an overall positive result improving the functioning of a relationship.

Lying

It’s important to start off this section by noting that lying doesn’t always constitute a “dark side” of relationships. Although many people have a negative connotation of lying, we have all lied or concealed information in order to protect the feelings of someone else. One research study found that only 27 percent of the participants agreed that a successful relationship must include complete honesty, which shows there is an understanding that lying is a communicative reality in all relationships. Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach, “Disentangling the Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication,” in The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, eds. Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2007), 15. Given this reality, it is important to understand the types of lies we tell and the motivations for and consequences of lying.

We tend to lie more during the initiating phase of a relationship. Mark L. Knapp, “Lying and Deception in Close Relationships,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 519. At this time, people may lie about their personality, past relationships, income, or skill sets as they engage in impression management and try to project themselves as likable and competent. For example, while on a first date, a person may lie and say they recently won an award at work. People sometimes rationalize these lies by exaggerating something that actually happened. So perhaps this person did get recognized at work, but it wasn’t actually an award. Lying may be more frequent at this stage, too, because the two people don’t know each other, meaning it’s unlikely the other person would have any information that would contradict the statement or discover the lie. Aside from lying to make ourselves look better, we may also lie to make someone else feel better. Although trustworthiness and honesty have been listed by survey respondents as the most desired traits in a dating partner, total honesty in some situations could harm a relationship. Mark L. Knapp, “Lying and Deception in Close Relationships,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 519. Altruistic lies are lies told to build the self-esteem of our relational partner, communicate loyalty, or bend the truth to spare someone from hurtful information. Part of altruistic lying is telling people what they want to hear. For example, you might tell a friend that his painting is really pretty when you don’t actually see the merit of it, or tell your mom you enjoyed her meatloaf when you really didn’t. These other-oriented lies may help maintain a smooth relationship, but they could also become so prevalent that the receiver of the lies develops a skewed self-concept and is later hurt. If your friend goes to art school only to be heavily critiqued, did your altruistic lie contribute to that?

As we grow closer to someone, we lie less frequently, and the way we go about lying also changes. In fact, it becomes more common to conceal information than to verbally deceive someone outright. We could conceal information by avoiding communication about subjects that could lead to exposure of the lie. When we are asked a direct question that could expose a lie, we may respond equivocally, meaning we don’t really answer a question. Mark L. Knapp, “Lying and Deception in Close Relationships,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 520. When we do engage in direct lying in our close relationships, there may be the need to tell supplemental lies to maintain the original lie. So what happens when we suspect or find out that someone is lying?

Research has found that we are a little better at detecting lies than random chance, with an average of about 54 percent detection. Mark L. Knapp, “Lying and Deception in Close Relationships,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 524. In addition, couples who had been together for an average of four years were better at detecting lies in their partner than were friends they had recently made. M. E. Comadena, “Accuracy in Detecting Deception: Intimate and Friendship Relationships,” in Communication Yearbook 6, ed. M. Burgoon (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1982), 446–72. This shows that closeness can make us better lie detectors. But closeness can also lead some people to put the relationship above the need for the truth, meaning that a partner who suspects the other of lying might intentionally avoid a particular topic to avoid discovering a lie. Generally, people in close relationships also have a truth bias, meaning they think they know their relational partners and think positively of them, which predisposes them to believe their partner is telling the truth. Discovering lies can negatively affect both parties and the relationship as emotions are stirred up, feelings are hurt, trust and commitment are lessened, and perhaps revenge is sought.

Sexual and Emotional Cheating

Extradyadic romantic activity (ERA) includes sexual or emotional interaction with someone other than a primary romantic partner. Given that most romantic couples aim to have sexually exclusive relationships, ERA is commonly referred to as cheating or infidelity and viewed as destructive and wrong. Despite this common sentiment, ERA is not a rare occurrence. Comparing data from more than fifty research studies shows that about 30 percent of people report that they have cheated on a romantic partner, and there is good reason to assume that the actual number is higher than that. Melissa Ann Tafoya and Brian H. Spitzberg, “The Dark Side of Infidelity: Its Nature, Prevalence, and Communicative Functions,” in The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, eds. Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2007), 207.

Although views of what is considered “cheating” vary among cultures and individual couples, sexual activity outside a primary partnership equates to cheating for most. Emotional infidelity is more of a gray area. While some individuals who are secure in their commitment to their partner may not be bothered by their partner’s occasional flirting, others consider a double-glance by a partner at another attractive person a violation of the trust in the relationship. You only have to watch a few episodes of The Jerry Springer Show to see how actual or perceived infidelity can lead to jealousy, anger, and potentially violence. While research supports the general belief that infidelity leads to conflict, violence, and relational dissatisfaction, it also shows that there is a small percentage of relationships that are unaffected or improve following the discovery of infidelity. Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach, “Disentangling the Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication,” in The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, eds. Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2007), 16. This again shows the complexity of the dark side of relationships.

The increase in technology and personal media has made extradyadic relationships somewhat easier to conceal, since smartphones and laptops can be taken anywhere and people can communicate to fulfill emotional and/or sexual desires. In some cases, this may only be to live out a fantasy and may not extend beyond electronic communication. But is sexual or emotional computer-mediated communication considered cheating? You may recall the case of former Congressman Anthony Weiner, who resigned his position in the US House of Representatives after it was discovered that he was engaging in sexually explicit communication with people using Twitter, Facebook, and e-mail. The view of this type of communication as a dark side of relationships is evidenced by the pressure put on Weiner to resign. So what leads people to engage in ERA? Generally, ERA is triggered by jealousy, sexual desire, or revenge. Melissa Ann Tafoya and Brian H. Spitzberg, “The Dark Side of Infidelity: Its Nature, Prevalence, and Communicative Functions,” in The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication, eds. Brian H. Spitzberg and William R. Cupach (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2007), 227.

Jealousy, as we will explore more later, is a complicated part of the emotional dark side of interpersonal relationships. Jealousy may also motivate or justify ERA. Let’s take the following case as an example. Julie and Mohammed have been together for five years. Mohammed’s job as a corporate communication consultant involves travel to meet clients and attend conferences. Julie starts to become jealous when she meets some of Mohammed’s new young and attractive coworkers. Julie’s jealousy builds as she listens to Mohammed talk about the fun he had with them during his last business trip. The next time Mohammed goes out of town, Julie has a one-night-stand and begins to drop hints about it to Mohammed when he returns. In this case, Julie is engaging in counterjealousy induction—meaning she cheated on Mohammed in order to elicit in him the same jealousy she feels. She may also use jealousy as a justification for her ERA, claiming that the jealous state induced by Mohammed’s behavior caused her to cheat.