” Persuasion- An Overview” by LibreTexts is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA

In his text The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in the 21st Century, Richard Perloff noted that the study of persuasion today is extremely important for five basic reasons:

- The sheer number of persuasive communications has grown exponentially.

- Persuasive messages travel faster than ever before.

- Persuasion has become institutionalized.

- Persuasive communication has become more subtle and devious.

- Persuasive communication is more complex than ever before (Perloff, 2003).

In essence, the nature of persuasion has changed over the last fifty years as a result of the influx of various types of technology. People are bombarded by persuasive messages in today’s world, so thinking about how to create persuasive messages effectively is very important for modern public speakers. A century (or even half a century) ago, public speakers had to contend only with the words printed on paper for attracting and holding an audience’s attention. Today, public speakers must contend with laptops, netbooks, iPads, smartphones, billboards, television sets, and many other tools that can send a range of persuasive messages immediately to a target audience. Thankfully, scholars who study

persuasion have kept up with the changing times and have found a number of persuasive strategies that help speakers be more persuasive.

What Is Persuasion?

Persuasion is an attempt to get a person to behave in a manner, or embrace a point of view related to values, attitudes, and beliefs, that he or she would not have done otherwise.

Change Attitudes, Values, and Beliefs

The first type of persuasive public speaking involves a change in someone’s attitudes, values, and beliefs. An attitude is defined as an individual’s general predisposition toward something as being good or bad, right or wrong, or negative or positive. Maybe you believe that local curfew laws for people under twenty-one are a bad idea, so you want to persuade others to adopt a negative attitude toward such laws.

You can also attempt to persuade an individual to change her or his value toward something. Value refers to an individual’s perception of the usefulness, importance, or worth of something. We can

value a college education or technology or freedom. Values, as a general concept, are fairly ambiguous and tend to be very lofty ideas. Ultimately, what we value in life actually motivates us to engage in a range of behaviors. For example, if you value technology, you are more likely to seek out new technology or software on your own. On the contrary, if you do not value technology, you are less likely to seek out new technology or software unless someone, or some circumstance, requires you to.

Lastly, you can attempt to get people to change their personal beliefs. Beliefs are propositions or positions that an individual holds as true or false without positive knowledge or proof. Typically, beliefs are divided into two basic categories: core and dispositional beliefs. Core beliefs are beliefs that people have actively engaged in and created over the course of their lives (e.g., belief in a higher power, belief in extraterrestrial life forms).

Dispositional beliefs, on the other hand, are beliefs that people have not actively engaged in but rather judgments that they make, based on their knowledge of related subjects, when they encounter a proposition. For example, imagine that you were asked the question, “Can stock cars reach speeds of one thousand miles per hour on a one-mile oval track?” Even though you may never have attended a stock car race or even seen one on television, you can make split-second judgments about your understanding of automobile speeds and say with a fair degree of certainty that you believe stock cars cannot travel at one thousand miles per hour on a one-mile track. We sometimes refer to dispositional beliefs as virtual beliefs (Frankish, 1998).

When it comes to persuading people to alter core and dispositional beliefs, persuading audiences to change core beliefs is more difficult than persuading audiences to change dispositional beliefs. For this reason, you are very unlikely to persuade people to change their deeply held core beliefs about a topic in a five- to ten-minute speech. However, if you give a persuasive speech on a topic related to an audience’s dispositional beliefs, you may have a better chance of success. While core beliefs may seem to be exciting and interesting, persuasive topics related to dispositional beliefs are generally better for novice speakers with limited time allotments.

Change Behavior

The second type of persuasive speech is one in which the speaker attempts to persuade an audience to change their behavior. Behaviors come in a wide range of forms, so finding one you think people should start, increase, or decrease shouldn’t be difficult at all. Speeches encouraging audiences to vote for a candidate, sign a petition opposing a tuition increase, or drink tap water instead of bottled water are all behavior-oriented persuasive speeches. In all these cases, the goal is to change the behavior of individual listeners.

Why Persuasion Matters

Frymier and Nadler enumerate three reasons why people should study persuasion (Frymier & Nadler, 2007). First, when you study and understand persuasion, you will be more successful at persuading others. If you want to be a persuasive public speaker, then you need to have a working understanding of how persuasion functions.

Second, when people understand persuasion, they will be better consumers of information. As previously mentioned, we live in a society where numerous message sources are constantly fighting for our attention. Unfortunately, most people just let messages wash over them like a wave, making little effort to understand or analyze them. As a result, they are more likely to fall for half-truths, illogical arguments, and lies. When you start to understand persuasion, you will have the skill set to actually pick apart the messages being sent to you and see why some of them are good and others are simply not.

Lastly, when we understand how persuasion functions, we’ll have a better grasp of what happens around us in the world. We’ll be able to analyze why certain speakers are effective persuaders and others are not. We’ll be able to understand why some public speakers can get an audience eating out of their hands, while others flop.

Furthermore, we believe it is an ethical imperative in the twenty-first century to be persuasively literate. We believe that persuasive messages that aim to manipulate, coerce, and intimidate people are unethical, as are messages that distort information. As ethical listeners, we have a responsibility to analyze messages that manipulate, coerce, and/or intimidate people or distort information. We also then have the responsibility to combat these messages with the truth, which will ultimately rely on our own skills and knowledge as effective persuaders.

Theories of Persuasion

Understanding how people are persuaded is very important to the discussion of public speaking. Thankfully, a number of researchers have created theories that help explain why people are persuaded. While there are numerous theories that help to explain persuasion, we are only going to examine three here: social judgment theory, cognitive dissonance theory, and the elaboration likelihood model.

Social Judgment Theory

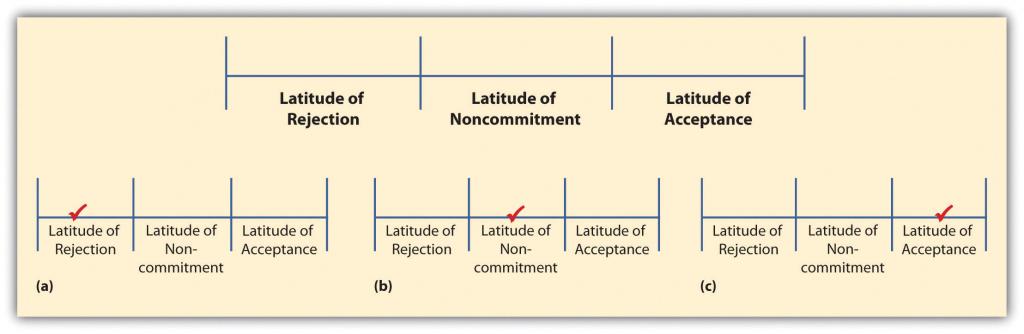

Muzafer Sherif and Carl Hovland created social judgment theory in an attempt to determine what types of communicative messages and under what conditions communicated messages will lead to a change in someone’s behavior (Sherif & Hovland, 1961). In essence, Sherif and Hovland found that people’s perceptions of attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors exist on a continuum including latitude of rejection, latitude of noncommitment, and latitude of acceptance (Figure 17.1 “Latitudes of Judgments”).

Figure 17.1 Latitudes of Judgments

Imagine that you’re planning to persuade your peers to major in a foreign language in college. Some of the students in your class are going to disagree with you right off the bat (latitude of rejection, part (a) of Figure 17.1 “Latitudes of Judgments”). Other students are going to think majoring in a foreign

language is a great idea (latitude of acceptance, part (c) of Figure 17.1 “Latitudes of Judgments”). Still others are really going to have no opinion either way (latitude of noncommitment, part (b) of Figure 17.1 “Latitudes of Judgments”). Now in each of these different latitudes there is a range of possibilities. For example, one of your listeners may be perfectly willing to accept the idea of minoring in a foreign

language, but when asked to major or even double major in a foreign language, he or she may end up in the latitude of noncommitment or even rejection.

Not surprisingly, Sherif and Hovland found that persuasive messages were the most likely to succeed when they fell into an individual’s latitude of acceptance. For example, if you are giving your speech on majoring in a foreign language, people who are in favor of majoring in a foreign language are more likely to positively evaluate your message, assimilate your advice into their own ideas, and engage in desired behavior. On the other hand, people who reject your message are more likely to negatively evaluate your message, not assimilate your advice, and not engage in desired behavior.

In an ideal world, we’d always be persuading people who agree with our opinions, but that’s not reality. Instead, we often find ourselves in situations where we are trying to persuade others to attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors with which they may not agree. To help us persuade others, what we need to think about is the range of possible attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors that exist. For example, in our foreign language case, we may see the following possible opinions from our audience members:

- Complete agreement. Let’s all major in foreign languages.

- Strong agreement. I won’t major in a foreign language, but I will double major in a foreign language.

- Agreement in part. I won’t major in a foreign language, but I will minor in a foreign language.

- Neutral. While I think studying a foreign language

can be worthwhile, I also think a college education can be complete without it. I really don’t feel strongly one way or the other.

- Disagreement in part. I will only take the foreign language classes required by my major.

- Strong disagreement. I don’t think I should have to take any foreign language classes.

- Complete disagreement. Majoring in a foreign language is a complete waste of a college education.

These seven possible opinions on the subject do not represent the full spectrum of choices, but give us various degrees of agreement with the general topic. So what does this have to do with persuasion? Well, we’re glad you asked. Sherif and Hovland theorized that persuasion was a matter of knowing how great the discrepancy or difference was between the speaker’s viewpoint and that of the audience. If the speaker’s point of view was similar to that of audience members, then persuasion was more likely. If the discrepancy between the idea proposed by the speaker and the audience’s viewpoint is too great, then the likelihood of persuasion decreases dramatically.

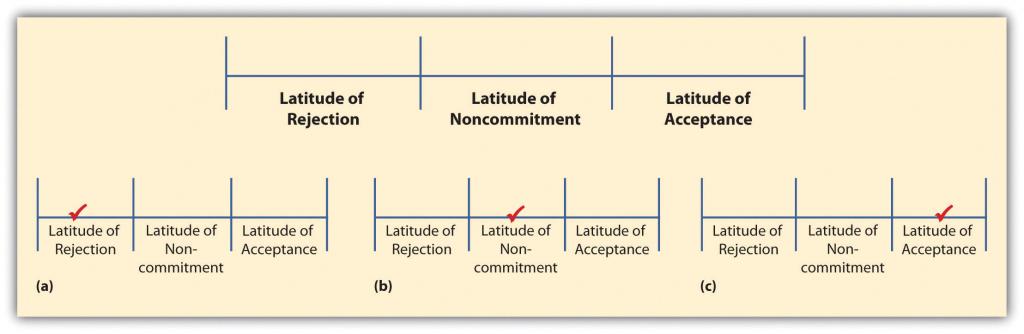

Figure 17.2 Discrepancy and Attitude Change

Furthermore, Sherif and Hovland predicted that there was a threshold for most people where

attitude change wasn’t possible and people slipped from the latitude of acceptance into the latitude of noncommitment or rejection. Figure 17.2 “Discrepancy and Attitude Change” represents this process. All the area covered by the left side of the curve represents options a person would agree with, even if there is an initial discrepancy between the speaker and audience member at the start of the speech. However, there comes a point where the discrepancy between the speaker and audience member becomes too large, which move into the options that will be automatically rejected by the audience member. In essence, it becomes essential for you to know which options you can realistically persuade your audience to and which options will never happen. Maybe there is no way for you to persuade your audience to major or double major in a foreign language, but perhaps you can get them to minor in a foreign language. While you may not be achieving your complete end goal, it’s better than getting nowhere at all.

Cognitive Dissonance Theory

In 1957, Leon Festinger proposed another theory for understanding how persuasion functions:

cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957). Cognitive dissonance is an aversive motivational state that occurs when an individual entertains two or more contradictory attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors simultaneously. For example, maybe you know you should be working on your speech, but you really want to go to a movie with a friend. In this case, practicing your speech and going to the movie are two cognitions that are inconsistent with one another. The goal of persuasion is to induce enough dissonance in listeners that they will change their attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors.

Frymier and Nadler noted that for cognitive dissonance to work effectively there are three necessary conditions: aversive consequences, freedom of choice, and insufficient external justification (Frymier & Nadler, 2007). First, for cognitive dissonance to work, there needs to be a strong enough aversive consequence, or punishment, for not changing one’s attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors. For example, maybe you’re giving a speech on why people need to eat more apples. If your aversive consequence for not eating apples is that your audience will not get enough fiber, most people will simply not be persuaded, because the punishment isn’t severe enough. Instead, for cognitive dissonance to work, the punishment associated with not eating apples needs to be significant enough to change behaviors. If you convince your audience that without enough fiber in their diets they are at higher risk for heart disease or colon cancer, they might fear the aversive consequences enough to change their behavior.

The second condition necessary for cognitive dissonance to work is that people must have a freedom of choice. If listeners feel they are being coerced into doing something, then dissonance will not be aroused. They may alter their behavior in the short term, but as soon as the coercion is gone, the original behavior will reemerge. It’s like the person who drives more slowly when a police officer is nearby but ignores speed limits once officers are no longer present. As a speaker, if you want to increase

cognitive dissonance, you need to make sure that your audience doesn’t feel coerced or manipulated, but rather that they can clearly see that they have a choice of whether to be persuaded.

The final condition necessary for cognitive dissonance to work has to do with external and internal justifications. External justification refers to the process of identifying reasons outside of one’s own control to support one’s behavior, beliefs, and attitudes. Internal justification occurs when someone voluntarily changes a behavior, belief, or attitude to reduce cognitive dissonance. When it comes to creating change through persuasion, external justifications are less likely to result in change than internal justifications (Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959).

Imagine that you’re giving a speech with the specific purpose of persuading college students to use condoms whenever they engage in sexual intercourse. Your audience analysis, in the form of an anonymous survey, indicates that a large percentage of your listeners do not consistently use condoms. Which would be the more persuasive argument: (a) “Failure to use condoms inevitably results in unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, including AIDS”—or (b) “If you think of yourself as a responsible adult, you’ll use condoms to protect yourself and your partner”? With the first argument, you have provided external justification for using condoms (i.e., terrible things will happen if you don’t use condoms). Listeners who reject this external justification (e.g., who don’t believe these dire consequences are inevitable) are unlikely to change their behavior. With the second argument, however, if your listeners think of themselves as responsible adults and they don’t consistently use condoms, the conflict between their self-image and their behavior will elicit cognitive dissonance. In order to reduce this cognitive dissonance, they are likely to seek internal justification for the view of themselves as responsible adults by changing their behavior (i.e., using condoms more consistently). In this case, according to cognitive dissonance theory, the second persuasive argument would be the one more likely to lead to a change in behavior.

Elaboration Likelihood Model

The last of the three theories of persuasion discussed here is the elaboration likelihood model created by Petty and Cacioppo (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). The basic model has a continuum from high elaboration or thought or low elaboration or thought. For the purposes of Petty and Cacioppo’s model, the term elaboration refers to the amount of thought or cognitive energy someone uses for analyzing the content of a message. High elaboration uses the central route and is designed for analyzing the content of a message. As such, when people truly analyze a message, they use cognitive energy to examine the arguments set forth within the message. In an ideal world, everyone would process information through this central route and actually analyze arguments presented to them. Unfortunately, many people often use the peripheral route for attending to persuasive messages, which results in low elaboration or thought. Low elaboration occurs when people attend to messages but do not analyze the message or use cognitive energy to ascertain the arguments set forth in a message.

For researchers of persuasion, the question then becomes: how do people select one route or the other when attending to persuasive messages? Petty and Cacioppo noted that there are two basic factors for determining whether someone centrally processes a persuasive message: ability and motivation. First, audience members must be able to process the persuasive message. If the language or message is too complicated, then people will not highly elaborate on it because they will not understand the persuasive message. Motivation, on the other hand, refers to whether the audience member chooses to elaborate on the message. Frymier and Nadler discussed five basic factors that can lead to high elaboration: personal relevance and personal involvement, accountability, personal responsibility, incongruent information, and need for cognition (Frymier & Nadler, 2007).

Personal Relevance and Personal Involvement

The first reason people are motivated to take the central route or use high elaboration when listening to a persuasive message involves personal relevance and involvement. Personal relevance refers to whether the audience member feels that he or she is actually directly affected by the speech topic. For example, if someone is listening to a speech on why cigarette smoking is harmful, and that listener has never smoked cigarettes, he or she may think the speech topic simply isn’t relevant. Obviously, as a speaker you should always think about how your topic is relevant to your listeners and make sure to drive this home throughout your speech. Personal involvement, on the other hand, asks whether the individual is actively engaged with the issue at hand: sends letters of support, gives speeches on the topic, has a bumper sticker, and so forth. If an audience member is an advocate who is constantly denouncing tobacco companies for the harm they do to society, then he or she would be highly involved (i.e., would engage in high elaboration) in a speech that attempts to persuade listeners that smoking is harmful.

Accountability

The second condition under which people are likely to process information using the central route is when they feel that they will be held accountable for the information after the fact. With accountability, there is the perception that someone, or a group of people, will be watching to see if the receiver remembers the information later on. We’ve all witnessed this phenomenon when one student asks the question “will this be on the test?” If the teacher says “no,” you can almost immediately see the glazed eyes in the classroom as students tune out the information. As a speaker, it’s often hard to hold your audience accountable for the information given within a speech.

Personal Responsibility

When people feel that they are going to be held responsible, without a clear external accounting, for the evaluation of a message or the outcome of a message, they are more likely to critically think through the message using the central route. For example, maybe you’re asked to evaluate fellow students in your public speaking class. Research has shown that if only one or two students are asked to evaluate any one speaker at a time, the quality of the evaluations for that speaker will be better than if everyone in the class is asked to evaluate every speaker. When people feel that their evaluation is important, they take more responsibility and therefore are more critical of the message delivered.

Incongruent Information

Some people are motivated to centrally process information when it does not adhere to their own ideas. Maybe you’re a highly progressive liberal, and one of your peers delivers a speech on the importance of the Tea Party movement in American politics. The information presented during the speech will most likely be in direct contrast to your personal ideology, which causes incongruence because the Tea Party ideology is opposed to a progressive liberal ideology. As such, you are more likely to pay attention to the speech, specifically looking for flaws in the speaker’s argument.

Need for Cognition

The final reason some people centrally process information is because they have a personality characteristic called need for cognition. Need for cognition refers to a personality trait characterized by an internal drive or need to engage in critical thinking and information processing. People who are high in

need for cognition simply enjoy thinking about complex ideas and issues. Even if the idea or issue being presented has no personal relevance, high need for cognition people are more likely to process information using the central route.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson, & Company.

Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203–210.

Frankish, K. (1998). Virtual belief. In P. Carruthers & J. Boucher (Eds.), Language and thought (pp. 249–269). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Frymier, A. B., & Nadler, M. K. (2007). Persuasion: Integrating theory, research, and practice. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

Perloff, R. M. (2003). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st Century (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 5–6.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 123–205.

Sherif, M., & Hovland, C. I. (1961). Social judgment: Assimilation and contrast effects in communication and attitude change. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.