29 Stakeholder Management

Click play on the following audio player to listen along as you read this section.

https://media.bccampus.ca/id/0_w4u22wam?width=608&height=70&playerId=23449753

A project is successful when it achieves its objectives and meets or exceeds the expectations of the stakeholders. But who are the stakeholders? Stakeholders are individuals who either care about or have a vested interest in your project. They are the people who are actively involved with the work of the project or have something to either gain or lose as a result of the project. When you manage a project to add lanes to a highway, motorists are stakeholders who are positively affected. However, you negatively affect residents who live near the highway during your project (with construction noise) and after your project with far-reaching implications (increased traffic noise and pollution).

NOTE: Key stakeholders can make or break the success of a project. Even if all the deliverables are met and the objectives are satisfied, if your key stakeholders aren’t happy, nobody’s happy.

The project sponsor, generally an executive in the organization with the authority to assign resources and enforce decisions regarding the project, is a stakeholder. The customer, subcontractors, suppliers, and sometimes even the government are stakeholders. The project manager, project team members, and the managers from other departments in the organization are stakeholders as well. It’s important to identify all the stakeholders in your project upfront. Leaving out important stakeholders or their department’s function and not discovering the error until well into the project could be a project killer.

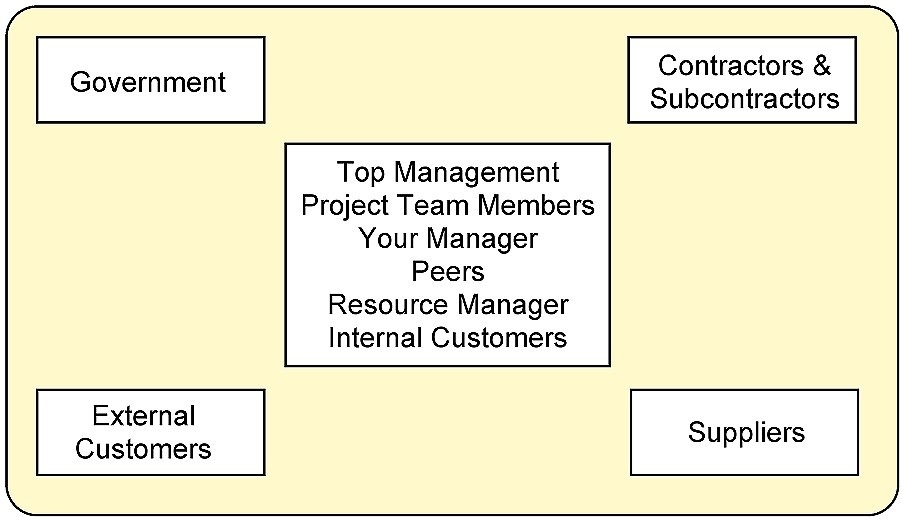

Figure 5.1 shows a sample of the project environment featuring the different kinds of stakeholders involved on a typical project. A study of this diagram confronts us with a couple of interesting facts.

First, the number of stakeholders that project managers must deal with ensures that they will have a complex job guiding their project through the lifecycle. Problems with any of these members can derail the project.

Second, the diagram shows that project managers have to deal with people external to the organization as well as the internal environment, certainly more complex than what a manager in an internal environment faces. For example, suppliers who are late in delivering crucial parts may blow the project schedule. To compound the problem, project managers generally have little or no direct control over any of these individuals.

Let’s take a look at these stakeholders and their relationships to the project manager.

Project Stakeholders

Top Management

Top management may include the president of the company, vice-presidents, directors, division managers, the corporate operating committee, and others. These people direct the strategy and development of the organization.

On the plus side, you are likely to have top management support, which means it will be easier to recruit the best staff to carry out the project, and acquire needed material and resources; also visibility can enhance a project manager’s professional standing in the company.

On the minus side, failure can be quite dramatic and visible to all, and if the project is large and expensive (most are), the cost of failure will be more substantial than for a smaller, less visible project.

Some suggestions in dealing with top management are:

- Develop in-depth plans and major milestones that must be approved by top management during the planning and design phases of the project.

- Ask top management associated with your project for their information reporting needs and frequency.

- Develop a status reporting methodology to be distributed on a scheduled basis.

- Keep them informed of project risks and potential impacts at all times.

The Project Team

The project team is made up of those people dedicated to the project or borrowed on a part-time basis. As project manager, you need to provide leadership, direction, and above all, the support to team members as they go about accomplishing their tasks. Working closely with the team to solve problems can help you learn from the team and build rapport. Showing your support for the project team and for each member will help you get their support and cooperation.

Here are some difficulties you may encounter in dealing with project team members:

- Because project team members are borrowed and they don’t report to you, their priorities may be elsewhere.

- They may be juggling many projects as well as their full-time job and have difficulty meeting deadlines.

- Personality conflicts may arise. These may be caused by differences in social style or values or they may be the result of some bad experience when people worked together in the past.

- You may find out about missed deadlines when it is too late to recover.

Managing project team members requires interpersonal skills. Here are some suggestions that can help:

- Involve team members in project planning.

- Arrange to meet privately and informally with each team member at several points in the project, perhaps for lunch or coffee.

- Be available to hear team members’ concerns at any time.

- Encourage team members to pitch in and help others when needed.

- Complete a project performance review for team members.

Your Manager

Typically the boss decides what the assignment is and who can work with the project manager on projects. Keeping your manager informed will help ensure that you get the necessary resources to complete your project.

If things go wrong on a project, it is nice to have an understanding and supportive boss to go to bat for you if necessary. By supporting your manager, you will find your manager will support you more often.

- Find out exactly how your performance will be measured.

- When unclear about directions, ask for clarification.

- Develop a reporting schedule that is acceptable to your boss.

- Communicate frequently.

Peers

Peers are people who are at the same level in the organization as you and may or may not be on the project team. These people will also have a vested interest in the product. However, they will have neither the leadership responsibilities nor the accountability for the success or failure of the project that you have.

Your relationship with peers can be impeded by:

- Inadequate control over peers

- Political maneuvering or sabotage

- Personality conflicts or technical conflicts

- Envy because your peer may have wanted to lead the project

- Conflicting instructions from your manager and your peer’s manager

Peer support is essential. Because most of us serve our self-interest first, use some investigating, selling, influencing, and politicking skills here. To ensure you have cooperation and support from your peers:

- Get the support of your project sponsor or top management to empower you as the project manager with as much authority as possible. It’s important that the sponsor makes it clear to the other team members that their cooperation on project activities is expected.

- Confront your peer if you notice a behaviour that seems dysfunctional, such as bad-mouthing the project.

- Be explicit in asking for full support from your peers. Arrange for frequent review meetings.

- Establish goals and standards of performance for all team members.

Resource Managers

Because project managers are in the position of borrowing resources, other managers control their resources. So their relationships with people are especially important. If their relationship is good, they may be able to consistently acquire the best staff and the best equipment for their projects. If relationships aren’t good, they may find themselves not able to get good people or equipment needed on the project.

Internal Customers

Internal customers are individuals within the organization who are customers for projects that meet the needs of internal demands. The customer holds the power to accept or reject your work. Early in the relationship, the project manager will need to negotiate, clarify, and document project specifications and deliverables. After the project begins, the project manager must stay tuned in to the customer’s concerns and issues and keep the customer informed.

Common stumbling blocks when dealing with internal customers include:

- A lack of clarity about precisely what the customer wants

- A lack of documentation for what is wanted

- A lack of knowledge of the customer’s organization and operating characteristics

- Unrealistic deadlines, budgets, or specifications requested by the customer

- Hesitancy of the customer to sign off on the project or accept responsibility for decisions

- Changes in project scope

To meet the needs of the customer, client, or owner, be sure to do the following:

- Learn the client organization’s buzzwords, culture, and business.

- Clarify all project requirements and specifications in a written agreement.

- Specify a change procedure.

- Establish the project manager as the focal point of communications in the project organization.

External customer

External customers are the customers when projects could be marketed to outside customers. In the case of Ford Motor Company, for example, the external customers would be the buyers of the automobiles. Also if you are managing a project at your company for Ford Motor Company, they will be your external customer.

Government

Project managers working in certain heavily regulated environments (e.g., pharmaceutical, banking, or military industries) will have to deal with government regulators and departments. These can include all or some levels of government from municipal, provincial, federal, to international.

Contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers

There are times when organizations don’t have the expertise or resources available in-house, and work is farmed out to contractors or subcontractors. This can be a construction management foreman, network consultant, electrician, carpenter, architect, or anyone who is not an employee. Managing contractors or suppliers requires many of the skills needed to manage full-time project team members.

Any number of problems can arise with contractors or subcontractors:

- Quality of the work

- Cost overruns

- Schedule slippage

Many projects depend on goods provided by outside suppliers. This is true for example of construction projects where lumber, nails, bricks, and mortar come from outside suppliers. If the supplied goods are delivered late or are in short supply or of poor quality or if the price is greater than originally quoted, the project may suffer.

Depending on the project, managing contractor and supplier relationships can consume more than half of the project manager’s time. It is not purely intuitive; it involves a sophisticated skill set that includes managing conflicts, negotiating, and other interpersonal skills.

Politics of Projects

Many times, project stakeholders have conflicting interests. It’s the project manager’s responsibility to understand these conflicts and try to resolve them. It’s also the project manger’s responsibility to manage stakeholder expectations. Be certain to identify and meet with all key stakeholders early in the project to understand all their needs and constraints.

Project managers are somewhat like politicians. Typically, they are not inherently powerful or capable of imposing their will directly on coworkers, subcontractors, and suppliers. Like politicians, if they are to get their way, they have to exercise influence effectively over others. On projects, project managers have direct control over very few things; therefore their ability to influence others – to be a good politician – may be very important

Here are a few steps a good project politician should follow. However, a good rule is that when in doubt, stakeholder conflicts should always be resolved in favour of the customer.

Assess the environment

Identify all the relevant stakeholders. Because any of these stakeholders could derail the project, you need to consider their particular interest in the project.

- Once all relevant stakeholders are identified, try to determine where the power lies.

- In the vast cast of characters, who counts most?

- Whose actions will have the greatest impact?

Identify goals

After determining who the stakeholders are, identify their goals.

- What is it that drives them?

- What is each after?

- Are there any hidden agendas or goals that are not openly articulated?

- What are the goals of the stakeholders who hold the power? These deserve special attention.

Define the problem

- The facts that constitute the problem should be isolated and closely examined.

- The question “What is the real situation?” should be raised over and over.

Culture of Stakeholders

When project stakeholders do not share a common culture, project management must adapt its organizations and work processes to cope with cultural differences. The following are three major aspects of cultural difference that can affect a project:

- Communications

- Negotiations

- Decision making

Communication is perhaps the most visible manifestation of culture. Project managers encounter cultural differences in communication in language, context, and candor.

Language is clearly the greatest barrier to communication. When project stakeholders do not share the same language, communication slows down and is often filtered to share only information that is deemed critical.

The barrier to communication can influence project execution where quick and accurate exchange of ideas and information is critical.

The interpretation of information reflects the extent that context and candor influence cultural expressions of ideas and understanding of information. In some cultures, an affirmative answer to a question does not always mean yes. The cultural influence can create confusion on a project where project stakeholders represent more than one culture.

Example: Culture Affects Communication in Mumbai

A project management consultant from the United States was asked to evaluate the effectiveness of a U.S. project management team executing a project in Mumbai, India. The project team reported that the project was on schedule and within budget. After a project review meeting where each of the engineering leads reported that the design of the project was on schedule, the consultant began informal discussions with individual engineers and began to discover that several critical aspects of the project were behind schedule. Without a mitigating strategy, the project would miss a critical window in the weather between monsoon seasons. The information on the project flowed through a cultural expectation to provide positive information. The project was eventually canceled by the U.S. corporation when the market and political risks increased.

Not all cultural differences are related to international projects. Corporate cultures and even regional differences can create cultural confusion on a project.

Example: Cultural Differences between American Regions

On a major project in South America that included project team leaders from seven different countries, the greatest cultural difference that affected the project communication was between two project leaders from the United States. Two team members, one from New Orleans and one from Brooklyn, had more difficulty communicating than team members from Lebanon and Australia.

Text Attributions

This chapter was adapted and remixed by Adrienne Watt from the following sources:

- Opening text and text under “Project Stakeholders” adapted from “Project Stakeholders” in Project Management by Merrie Barron and Andrew Barron. Licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Text under “Politics of Projects” adapted from “The Politics of Projects” in Project Management by Merrie Barron and Andrew Barron. Licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Text under “Culture of Stakeholders” adapted from Culture of Stakeholders in Project Management From Simple to Complex by author(s) whose names have been removed at the request of the original publisher. Licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence

- Text under “Relationship Building Tips adapted from How to Build Relationships with Stakeholders by Erin Palmer. © CC BY (Attribution).

- Text under “Tools to Help Stakeholder Management” adapted from

Project Decelerators – Lack of Stakeholder Support by Jose Solera. © CC BY (Attribution).