47 Cost Estimation

Estimate Costs and Determine Budgets

Ultimately cost, the number management typically cares about most in a for-profit organization, is determined by price. For many projects, it’s impossible to know the exact cost of an endeavor until it is completed. Stakeholders can agree on an intended value of a project at the beginning, and that value has an expected cost associated with it. But you may not be able to pin down the cost more precisely until you’ve done some work on the project and learned more about it.

To estimate and manage costs effectively, you need to understand the different types of costs:

- Direct Costs: “An expense that can be traced directly to (or identified with) a specific cost center or cost object such as a department, process, or product” (Business Dictionary, n.d.). Examples of direct costs include labor, materials, and equipment. A direct cost changes proportionately as more work is accomplished.

- Direct Project Overhead Costs: Costs that are directly tied to specific resources in the organization that are being used in the project. Examples include the cost of lighting, heating, and cleaning the space where the project team works. Overhead does not vary with project work, so it is often considered a fixed cost.

- General and Administrative (G&A) Overhead Costs: The “indirect costs of running a business,” such as IT support, accounting, and marketing” (Tracy, n.d., para. 1).

The type of contract governing your project can affect your consideration of costs. The two main types of contracts are fixed-price and cost-plus. Fixed price is the more predictable of the two with respect to final cost, which can make such contracts appealing to the issuing party. But “this predictability may come with a price. The seller may realize the risk that he is taking by fixing a price and so will charge more than he would for a fluid price, or a price that he could negotiate with the seller on a regular basis to account for the greater risk the seller is taking” (Symes, 2018).

Many contracts include both fixed-price and cost-plus features. For example, they might have a fixed price element for those parts of the contract that have low variability and are under the direct control of the project team (e.g., direct labor) but have variable cost elements for those aspects that have a high degree of uncertainty or are outside the direct control of the project team (e.g., fuel costs or market driven consumables).

It is important to come up with detailed estimates for all the project costs. Once this is compiled, you add up the cost estimates into a budget plan. It is now possible to track the project according to that budget while the work is ongoing.

Often, when you come into a project, there is already an expectation of how much it will cost or how much time it will take. When you make an estimate early in the project without knowing much about it, that estimate is called a rough order-of-magnitude estimate (or a ballpark estimate). This estimate will become more refined as time goes on and you learn more about the project. Here are some tools and techniques for estimating cost:

- Determination of Resource Cost Rates: People who will be working on the project all work at a specific rate. Any materials you use to build the project (e.g., wood or wiring) will be charged at a rate too. Determining resource costs means figuring out what the rate for labor and materials will be.

- Vendor Bid Analysis: Sometimes you will need to work with an external contractor to get your project done. You might even have more than one contractor bid on the job. This tool is about evaluating those bids and choosing the one you will accept.

- Reserve Analysis: You need to set aside some money for cost overruns. If you know that your project has a risk of something expensive happening, it is better to have some cash available to deal with it. Reserve analysis means putting some cash away in case of overruns.

- Cost of Quality: You will need to figure the cost of all your quality-related activities into the overall budget. Since it’s cheaper to find bugs earlier in the project than later, there are always quality costs associated with everything your project produces. Cost of quality is just a way of tracking the cost of those activities. It is the amount of money it takes to do the project right.

Once you apply all the tools in this process, you will arrive at an estimate for how much your project will cost. It’s important to keep all of your supporting estimate information. That way, you know the assumptions made when you were coming up with the numbers. Now you are ready to build your budget plan.

Estimating Costs to Compare and Select Projects

During the conceptual phase when project selection occurs, economic factors are an important consideration in choosing between competing projects. To compare the simple paybacks or internal rates of return between projects, an estimate of the cost of each project is made. The estimates must be accurate enough so that the comparisons are meaningful, but the amount of time and resources used to make the estimates should be appropriate to the size and complexity of the project. The methods used to estimate the cost of the project during the selection phase are generally faster and consume fewer resources than those used to create detailed estimates in later phases. They rely more on the expert judgment of experienced managers who can make accurate estimates with less detailed information. Estimates in the earliest stages of project selection are usually based on information from previous projects that can be adjusted—scaled—to match the size and complexity of the current project or developed using standardized formulas.

Analogous Estimate

An estimate that is based on other project estimates is an analogous estimate. If a similar project cost a certain amount, then it is reasonable to assume that the current project will cost about the same. Few projects are exactly the same size and complexity, so the estimate must be adjusted upward or downward to account for the differences. The selection of projects that are similar and the amount of adjustment needed is up to the judgment of the person who makes the estimate. Normally, this judgment is based on many years of experience estimating projects, including incorrect estimates that were learning experiences for the expert.

Less-experienced managers who are required to make analogous estimates can look through the documentation that is available from previous projects. If projects were evaluated using the Darnall-Preston Complexity Index (DPCI), the manager can quickly identify projects that have profiles similar to the project under consideration, even if those projects were managed by other people.

The DPCI assesses project attributes, enabling better-informed decisions in creating the project profile. This index assesses the complexity level of key components of a project and produces a unique project profile. The profile indicates the project complexity level, which provides a benchmark for comparing projects and information about the characteristics of a project that can then be addressed in the project execution plan. It achieves this objective by grouping 11 attributes into four broad categories: internal, external, technological complexity, and environmental.

Comparing the original estimates with the final project costs on several previous projects with the same DPCI ratings gives a less-experienced manager the perspective that it would take many years to acquire by trial and error. It also provides references the manager can use to justify the estimate.

Example: Analogous Estimate for John’s Move

John sold his apartment and purchased another one. It is now time to plan for the move. John asked a friend for advice about the cost of his move. His friend replied, “I moved from an apartment a little smaller than yours last year and the distance was about the same. I did it with a 14-foot truck. It cost about $575 for the truck rental, pads, hand truck, rope, boxes, and gas.” Because of the similarity of the projects, John’s initial estimate of the cost of the move was less than $700, so he decided that the cost would be affordable and the project could go forward.

Parametric Estimate

If the project consists of activities that are common to many other projects, average costs are available per unit. For example, if you ask a construction company how much it would cost to build a standard office building, the estimator will ask for the size of the building in square feet and the city in which the building will be built. From these two factors—size and location—the company’s estimator can predict the cost of the building. Factors like size and location are parameters—measurable factors that can be used in an equation to calculate a result. The estimator knows the average cost per square foot of a typical office building and adjustments for local labor costs. Other parameters such as quality of finishes are used to further refine the estimate. Estimates that are calculated by multiplying measured parameters by cost-per-unit values are parametric estimates.

Activity-Based Estimates

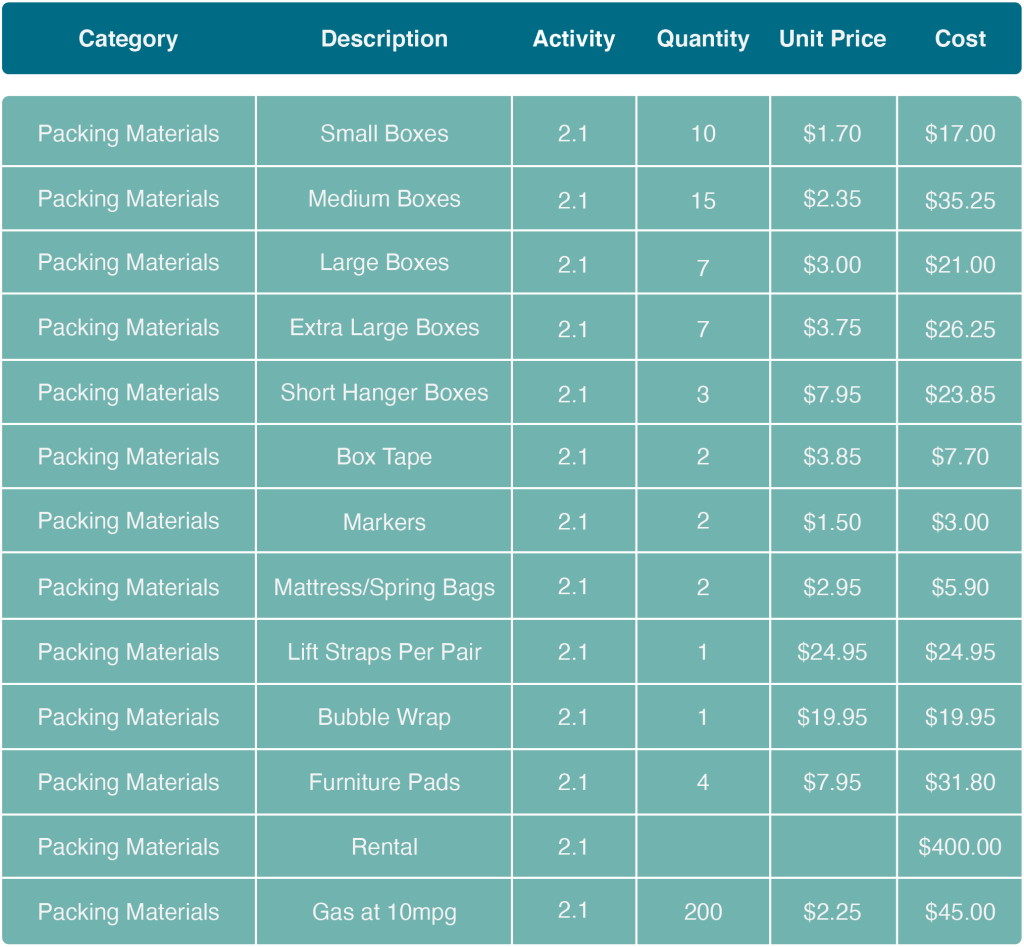

An activity can have costs from multiple vendors in addition to internal costs for labor and materials. Detailed estimates from all sources can be reorganized so those costs associated with a particular activity can be grouped by adding the activity code to the detailed estimate (Figure 6-1). The detailed cost estimates can be sorted and then subtotaled by activity to determine the cost for each activity.

Text Attributions

This chapter of Project Management is a derivative the following texts:

Essentials of Project Management by Adam Farag is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.